Chapter 7 - Developing your abilities as a reporter and interviewer

Chapter 7 web version

In the book version of this chapter we will cover:

- The life cycle of a story and how to report on it at every point

- The difference between live news and scheduled editions or bulletins

- The value of in-depth reporting

- Tackling challenging reporting assignments including:

- Reporting from press conferences

- Covering public meetings

- Reporting on public events

- Court reporting

- Difficult interviews and how to handle them.

At the end of the chapter are a range of assignments and projects to enable you to practise what you have learned.

Here we will look at

- A wide range of examples to illustrate the tuition here on challenging reporting assignments

- A wide range of videos illustrating the material covered here

- A wealth of links to further information.

Always have the book version of Multimedia Journalism to hand while you use this website – the off- and on-line versions are designed to work together.

7B1 Live news vs the edition, rolling news vs the scheduled bulletin

In the book you will find an explanation of the news cycle and the difference between live news and the edition or scheduled bulletin.

Here we'll add resources that enable you to look into the question of news and story cycles in greater depth.

Pat Long, head of news development at the (London) Times and Sunday Times, on Why Newspapers should steer away from the MTV model

put the position succinctly here: http://www.journalism.co.uk/news-commentary/-why-newspapers-should-steer-away-from-the-mtv-model-/s6/a556217/

A Reynolds Journalism Institute video on covering an election via multimedia reporting online and print:

It gets going about three minutes in:

Designing news for mobile consumption. David Cohn of Circa, a mobile-first newsroom:

David Carr, New York Times, on online vs print: http://youtu.be/upbZelyqVOY

The personal news cycle – how consumers choose to get their news: www.americanpressinstitute.org/publications/reports/survey-research/personal-news-cycle/

Tracing the future of News – a Reuters report on patterns of news consumption: www.slideshare.net/NicNewman/reuters-institute-digital-news-report-2014-tracking-the-future-of-news

The future of Journalism "the audience will determine the future of news" - a TED video.

Will the net kill print journalism?

Print vs Online journalism. Students debate the pros and cons:

Stanford conference on the future of journalism

7B2 Challenging reporting assignments

In the book version of this module you'll find detailed explanation of how to report in a range of situations including:

- At a press conference

- At a public meeting

- At major public events.

Here, we'll take a look at a range of contemporary examples of how particular press conferences, public meetings and public events are treated, by a range of media, and the differing stories they get out of them.

They include:

- A product launch

- A police press conference

- A public meeting

- A public event.

A product launch

Mariah Carey launches a drink

Take a look at this video. What's the story? What's missing and what do you need to find out to tell it?

![]() Consider some angles for this story, and different audiences for it. Don't read on until you have considered them.

Consider some angles for this story, and different audiences for it. Don't read on until you have considered them.

OK there's the drink, but you don't learn much about it. Is it alcoholic or non? Where will it be sold? What will it cost?

What about the way the drink is connected to social media? There's a tech story here too, but what exactly does downloading the app get you? What is the app called? Where do you find it?

Her fans are one key audience.

Another audience is made up of those interested in the technology of linking a physical product with online information.

How various media outlets reported on this press release, and the angles they took

Reporting on the drink

Vibe

www.vibe.com/article/mariah-carey-butterfly-beverage

A straight report on the drink. Here's the intro:

"Mariah Carey's got the juice. After a week of releasing her Elusive Chanteuse LP, Mimi unveiled her new Go N'syde bottle, called "Butterfly", a pink non-alcoholic drink described as “a melodic beverage inspired by the magic of Mariah Carey.”

Reporting on the social media aspect

Yahoo News, picked up from PR Newswire

In the second paragraph you get this: "by activating each Butterfly Bottle with a smart phone or ipad, Fans Have a Chance to Win a Trip to Mariah's Summer Party in New York and Get Access to Exclusive 40/40 Club Events."

That angle was also chosen by, among others, Consumer Electrics and Mobile Marketeer (www.mobilemarketer.com/cms/news/music/18046.html)

Its intro gives a better explanation of how things work: "Mariah Carey-sponsored beverage Butterfly is teaming up with augmented reality integration platform Go N’Syde to provide an exclusive, virtual experience for fans of the singer and the soft drink."

Mobile Commerce news looked in detail at the QR code aspect of the marketing www.qrcodepress.com/augmented-reality-experience-sold-alongside-mariah-careys-new-drink/8527422/

![]() We look at QR codes in Chapter 18.

We look at QR codes in Chapter 18.

Reporting on the broader business angle

Singers Room headlined its report: Interesting! Mariah Carey Launches Social Media-Based 'Butterfly' Beverage

Here's a link: http://singersroom.com/content/2014-06-10/Interesting-Mariah-Carey-Launches-Social-Media-Based-Butterfly-Beverage/

The story reads: "Mariah's empire is expanding…she's done fragrances, clothing, and of course, music, and now the R&B diva will get into the beverage business... but it’s not JUST a drink: with an app on your smartphone, scan the bottle and you’ll be transported to Mariah World with exclusive messages from Mimi, videos, and photos.

How the Mail Online covered the story

OK, that angle might not immediately have come to mind, but if you are reporting on a gossip/celeb/showbiz site it’s the sort of thing you ought to have thought about when you looked at the video and stills.

Junk Food Guy bought one and reviewed what it tastes like http://www.junkfoodguy.com/2014/06/06/mariahbutterfly/#sthash.QRGGpArp.dpbs

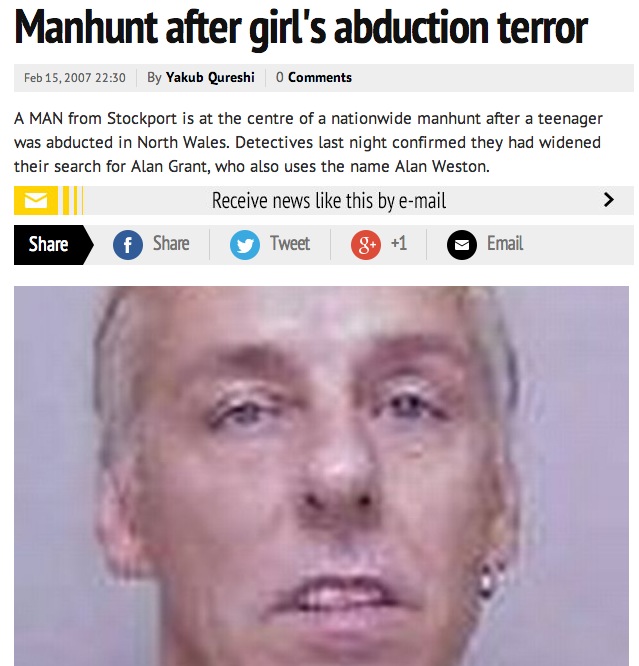

Example of reporting a police appeal

Here’s an example of what can be reported from a police appeal, taken from the web edition of the Manchester Evening News.

The links take you to the full story.

First the police appeal and a great deal can be said.

The headline is: Manhunt after girl's abduction terror

www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/news/s/226/226180_manhunt_after_girls_abduction_terror.html

The story is clearly defamatory of the man – it accuses him of being a rapist, and abductor, and it is in contempt of court because an arrest warrant has been issued, hence the case is what is known as active and no matters that are likely to form part of a trial should be discussed.

It says he snatched a 15-year-old girl from the street and subjected her to a horrendous ordeal. He is said to be a danger to the public and should not be approached. He is also said to have raped in the past.

But the law balances the man’s rights with the public’s right to know. The public needs protecting, in the opinion of the police, and this consideration takes precedence over other concerns.

But that only applies while he is being hunted. Once he is caught, your protection goes. So you have to do all you can to check, before you publish, that he has not been caught. As soon as he has, you can say very little.

Here’s how the story was reported in the MEN after he was caught, but before he had been charged:

www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/news/s/226/226359_man_charged_with_abducting_girl_15.html

The headline is: Man charged with abducting girl, 15

Now the assertions are peppered with allegedlys, but the sequence of events is still recounted. The law text books will indicate that this is dangerous.

Once he has been charged, here is an even briefer report:

Headline: Man charged over teen abduction

www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/news/s/226/226403_man_charged_over_teen_abduction.html

Now there are no accounts of events. The report concentrates on a man being charged with an alleged abduction and two serious sexual assaults.

Finally, just to complete the story, here is the report of his subsequent trial:

Headline: Man who raped 15-year-old jailed for life

www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/news/s/233/233118_man_who_raped_15yearold_jailed_for_life.html

Examples of reporting from public meetings

These videos show the sort of stories that can be gathered at routine public meetings.

Hospital closures protest meeting

This video is an edited account of a public meeting held in the London borough of Hammersmith and Fulham concerning planned closures to accident and emergency departments in a range of local hospitals.

![]() Can you identify who has published this video report? Do you detect any agenda in the report? Don’t read on until you have decided.

Can you identify who has published this video report? Do you detect any agenda in the report? Don’t read on until you have decided.

The report is from Hammersmith and Fulham council. It’s fair to say that the council is opposed to the planned closures, as are those at the meeting. There is some information from those on the panel about why they want to make these closures, but do you feel from this video that you could give a full account of their reasons?

Post office closure protest meeting

Here’s another example of a public meeting from Hammersmith and Fulham council in London.

Residents have come to tell Post Office officials what they think of their plans to close some post offices.

Is there an agenda behind this story?

There could be, because it appears that residents want to retain post offices, and the council supports them in this. Because the decision on closures is one for central government, this report could be seen as Hammersmith and Fulham lobbying against the plan and making clear to local electors that the decision is not down to its councillors.

The Post Office representative at the meeting says it is losing £170m, because the number of people using post offices has declined dramatically.

A string of speakers follows. None of them are named, which makes it impossible to identify what interests they might be representing. Quotes from unidentified speakers would look very poor in print, and they ought not to be tolerated in video reports.

There is a strong editorial stance behind the report – it appears designed to show residents how much the council is doing to fight post office closures. It ends: “Surely sense will prevail.”

Such a comment would be unacceptable in a text report in a traditional local newspaper. Local TV has always allowed its reporters more leeway in presenting opinions – either their own or those they claim to have drawn from those they have spoken to, but to whom they do not attribute the views directly.

Let’s remember one of the basic tenets of objective reporting that we covered in Chapter 1. If you want to express an opinion, get someone to express it, and attribute the view to that person. That’s worth remembering, whatever medium you are reporting in.

An example of reporting from a major public event

Notting Hill carnival

The Notting Hill carnival is one of the biggest public events in the world. For three days the streets of this area of west London are taken over by an incredibly vibrant and popular display attended by hundreds of thousands of people.

Here's a video that captures the atmosphere and enjoyment of the event:

Here's another side of carnival:

![]() if you were reporting on carnival, and had seen both sides of it, how would you structure your report?

if you were reporting on carnival, and had seen both sides of it, how would you structure your report?

If we imagine both films having been made at the same year’s carnival, clearly they don’t, individually, give a clear impression of how things were. A balanced report would cover both aspects. You might write a text report that covered both aspects, and then embed the two videos to give readers a clear understanding of both sides of things. Alternatively, you could use elements from both and edit the footage into one coherent report that covered both sides of the story.

As that last video shows, reporting can be dangerous. In the Sky film the cameraman is behind police lines. Sometimes reporters are unprotected in situations in which their lives could be in danger. Each of us has to decide – both as a general principle and in each individual situation – how much risk we are prepared to take.

But risk assessment is an important element in the daily lives of multimedia journalists, who may be carrying expensive kit: a sophisticated mobile, a video camera and more. All employers must take such risks into account when they send us out.

Court reporting

Even if you never expect to have to report on court, I do urge you to read up a little about court reporting. Here are a couple of essential links to information:

The BBC Journalism Academy's guidance for court reporting in England and Wales www.bbc.co.uk/academy/journalism/article/art20130702112133645

The BBC Academy on court reporting and social media

www.bbc.co.uk/academy/journalism/law/courts/article/art20130702112133638

Why court reporting is important www.thenewsmanual.net/Manuals%20Volume%203/volume3_64.htm

A full guide to court reporting in England and Wales

Legal essentials

We have in the UK what is known as absolute privilege for reports of court proceedings that are fair, accurate and contemporaneous. (That’s a higher level of protection than we have for what we say and write about public meetings, where we have just qualified privilege.) If we fulfill that three-part (fair, accurate and contemporaneous) test we are safe. It means that, for example, however defamatory something said in court, and reported by us, might be, no action can be taken against us.

But we also need to be aware of any orders, made by the court, that restrict our right to report freely.

If we are covering a preliminary hearing – of a case that will go on to be tried in full at another time and quite possibly in a different court – we are tightly restricted in what we can say.

Before the event – research

HM Courts and Tribunals service has details of all courts in England and Wales here: www.justice.gov.uk/about/hmcts/

For Scottish courts, go here: www.scotcourts.gov.uk/

The HM Courts and Tribunals Service site gives details of all Crown Courts and the cases being tried there via its court and tribunals finder https://courttribunalfinder.service.gov.uk/, but it doesn’t list magistrates' courts because things change too fast. For those lists you need to contact the court. The Scottish site covers the equivalent courts in that country.

The list of forthcoming cases is the starting point for court reporting. These tell you when a particular case is due to come before a particular court, but things change. It is only ever a rough guide, and you need to check it with the court. The people to get to know there are those in the magistrates’ clerks’ office.

Before the event – reporting

Here you have to be very careful. We have a principle under English law that nothing should be written or said that might prejudice a person’s right to a free trial. Our interpretation of that is far stricter than in, say the USA, where comment and allegations can be hurled at a defendant and the assumption is that the jury will be able to put that out of their minds and judge them purely on the case that is presented to them in court.

Just to repeat something we said earlier when looking at police appeals, in the UK the principle is that the court’s role is to determine what happened in a case. If we write anything that would tend to prejudge what happened, we are usurping the role of the court and hence could be said to be in contempt of it. So once a person is arrested, or charged, or if a warrant for their arrest has been issued, proceedings are said to be active. That means we can say very little about the case. We also have to be very careful when covering events that are likely, at a later date, to be the subject of a court case.

Or at least, that’s what the law says.

Let’s think about a case, for example where there has been a road accident and someone has been killed.

It means, if we follow the letter of the law, that we can only give a very bland outline of the accident. We can’t say anything that would suggest where blame lies. And we can’t quote witnesses in case they were in shock and later recall more clearly what happened. If we have published their hazy account, the logic goes, they may be reluctant to change their story in court to a version that is close to the truth, once they have had a chance to recall it.

So if a baby is killed when a car, for some reason, hits him while he is being pushed in his pushchair along the pavement, there are many possible explanations for the accident, but we have to leave it up to the court to decide which is the right one.

The driver might be tried for the accident. They might be found to be guilty of one of a number of driving offences. Or they might be cleared.

But many media organisations allow witnesses and others to give their interpretation of what happened. That happened when the story I have outlined above was reported in Telegraph.co.uk

www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/1560946/Baby-killed-after-car-careers-off-London-road.html

Can you think why that report is safe? Don't read on until you have your answer.

The report doesn’t identify the driver. When you cover such a story in this way, you have to be certain that no one who might later be on a jury trying him can identify the driver from it.

What happens with a really major story that involves really serious charges – alleged terrorists plotting mass murder – for example? When an alleged plot to blow up nine jets using liquid explosives hidden in innocuous carry-on packages was uncovered in the UK, 23 Muslims were arrested.

Many newspapers carried headlines that assumed the allegations were true. Here’s The Sun:

Reports carried quotes from politicians and police chiefs such as "we have stopped an attempt to commit mass murder on an unimaginable scale".

There were pictures of the accused, which could be a problem if any witness were asked to identify one of the men in court. The jury might find it impossible to be sure that the witness remembered the face they saw carrying out a crime, rather than the one they saw in a newspaper.

The media lawyer Duncan Lamont pondered, in a Guardian article

www.guardian.co.uk/media/2006/aug/21/mondaymediasection.israel , why it was that, when a number of suspects are arrested when allegedly planning a terrorist atrocity, the usual rules are ignored by the press.

He asked: “Those arrested are as entitled to a fair trial as a shoplifter or someone who had actually committed a crime as serious as murder. So what happened to our contempt of court laws?”

The media acted as it did, he says, because it felt protected in a number of ways.

One was the number of arrests made. The courts, he explains, had acknowledged in a series of cases that even prejudicial material published at the time of arrests fades in the minds of potential jurors over time, and hence ensuring a fair trial, where defendants can still be assumed to be innocent unless proved otherwise. He makes the point that, with so many possible defendants in this case, even massively prejudicial allegations (such as the discovery of a martyrdom tape) does not, arguably, taint every member of such a large group.

There was also the international dimension of the alleged terror plot. Government officials in Pakistan and the US were releasing information about the plot and those associated with it.

Such announcements, Lamont says, have the protection in libel law of qualified privilege, because they are made – and published – for the positive purpose of providing the public with appropriate information. For that reason, he goes on, there is no risk of a libel claim from any of the suspects.

However, he stresses, if those arrested are subsequently found not guilty, huge libel claims are a very real possibility.

There is a balance to be struck here because, while the law of contempt could be used to punish British newspapers for reporting foreign officials' comments about ongoing criminal cases, the Human Rights Act equation is firmly on the side of freedom of expression. In such cases, Lamont explains, intrusions into the private life of the suspects, and the risk to their right to a free trial, have to be balanced against the interests and concerns of the hundreds of thousands of people who have had their flights disrupted and who are entitled to know the reason for that now, rather than in a couple of years' time.

The problem here is that what is taught in media law books and courses is often out of line with what the media actually does. You must know the law, but also to follow the guidance of your editor, once you have one. Many editors make their judgements on what they are reasonably sure of. If they are convinced a person is guilty then they are inclined to say more than they would in a less clear-cut case. But such a strategy has proven very expensive for some newspapers who have assumed guilt in very high profile cases and subsequently been proved wrong.

If a case has been notorious you may well have covered it in the past. Other cases come to your attention first only when they come to court. If you spot an interesting case, then you need to find out all you can about it. Check what, if anything, has been written before. If it is a really big case you may need to gather material for telling the full story once the court case has finished. Such pieces are known as backgrounders. While gathering material for them you must be very careful not to be in contempt of court. If you interview people who will later be witnesses in the court case you might affect how they deliver their evidence. Perhaps they exaggerate for your benefit, then feel they must stick with the exaggeration when giving evidence.

At the event

Courts are very strict on how you can report on them. In England and Wales, photography and tape-recording in court is strictly forbidden. But tweeting, or what the courts tend to define as 'live, text-based communication' is generally allowed, following a ruling by the Lord Chief Justice, and courts in Northern Ireland and Scotland are expected to do so at some point.

If you are a bona fide reporter, you do not need permission to tweet from court because it is assumed that your communications are accurate reports of proceedings, rather than comments that may be prejudicial to the case.

Judges can still ban tweeting for the reasons they can restrict any form of reporting – if it could interfere with justice – but they'll need to tell you.

Here's the BBC's Dominic Casciani on the power of tweeting from court:

www.bbc.co.uk/academy/journalism/law/courts/article/art20130702112133638

"The power of Twitter as a court-reporting service started to become clear at the end of the inquests into the 7 July London bombings of 2005," he says.

Casciani explains that, in May 2011, the coroner, Lady Justice Hallett, delivered a comprehensive and at times very moving series of verdicts. He says he tweeted every key quote or line from what she said. As he did so, he discovered that a live online audience was following his tweets, and retweeting what he was reporting.

Casciani characterises what was happening like this: "It was a digital version of the pub conversation. Colleagues using Twitter on other big court stories had similar experiences. "

But it was, he says, the overwhelming public interest in the Stephen Lawrence murder trial which confirmed that live social media reporting was at the heart of the reporter's job.

In this case the judge had to be convinced that they should allow social media reporting. The trial opened with an application by the prosecution to ban the use of social media out of fear of prejudicial commentary. But, following a BBC challenge, the judge accepted that Twitter was not being used by responsible journalists as a means to comment on an unfolding case, but rather as a way to report court cases as they happen, informing both the public and their colleagues in the newsroom.

However, there are concerns that tweeting will get in the way of in-depth court reporting. Dominic Ball, who edits the 6pm news bulletin on BBC Radio 4, said in a blog post at www.holyrood.com which is no longer available: “My concern is, if the focus is getting information out on Twitter then it’s not on the nuances of the package. Do we want our correspondents to be storytellers or stenographers?”

English courts also don’t like pictures to be taken in what they call the precincts of the court – that’s generally interpreted to mean that the building shouldn’t be visible in a picture. This rule is regularly flouted. Reporters often deliver a piece to camera with the court’s sign prominent in the background. Once again, once you are in a job, follow your employer’s guidelines.

You may well want to get stills or video of key people in a trial: defendants if they are on bail, victims or lawyers. If you do, know your publication’s policy on such material.

Text is key to court reporting. You will have to take a clear note of proceedings whether it is to be printed, published as text online or used as the basis of an audio or video report.

Your report must be fair, accurate and published contemporaneously. Fair means you give both sides, even if a person is found guilty; accurate in that you have not introduced any errors; and contemporaneous, which means published as soon as possible. If you are on a website that’s going to be the same day probably, if on a paper or a magazine then in the next available issue.

There’ll be a list of cases scheduled for the day pinned up in the court, and you can get a copy – sometimes for free, sometimes at a charge, depending on the policy of the particular court. In magistrates courts the list is subject to change, depending on the duties of defence and prosecution, and the presence of defendants and witnesses. Crown court lists vary much less, because cases tend to be longer and have time slots allocated to them.

The case list will give you the name and age of defendants and details of what they are charged with. Some courts add further details, such as when and where the alleged offence occurred.

If you are covering crown court, you are likely to have been sent there with a particular case in mind. At magistrates' you are likely to be going through the lists to see which cases look the most interesting.

A large number of defendants plead guilty in magistrates’ courts, and cases are often dealt with swiftly.

Who’s who

At magistrates' there may be a salaried district judge sitting alone, or a number of unpaid volunteer magistrates, also known as justices of the peace (JPs). One will be the chairman and will do most, if not all, the talking.

Then there are the magistrates' clerks – one or more, who are responsible for running the court and advising magistrates on points of law, and who sit at a desk in front of the bench.

Lawyers – for prosecution and defence – sit facing the bench. They stand when addressing the bench. Everyone stands – including you – when district judge or magistrates enter or leave the court room.

Defendants stand in the dock, which can either be behind the lawyers, or to one side, or may sit beside the defence solicitor. Sometimes a barrister defends. With very minor cases, such as petty traffic offences, defendants usually don’t attend.

Witnesses give their evidence from a witness box, which is usually on one side of the court and towards the front. Witnesses do not enter court before they have given their evidence, for fear that they will be tempted to change their story to fit in with what they hear, but they can stay after they have been dealt with. Don’t talk to witnesses outside the court before they have given evidence.

You sit on the press bench, which is usually to one side of the court. Probation officers may have their own bench or share yours.

At crown court a judge will sit on the bench, and there will be benches for the jury, who are called in for more serious cases where a not guilty plea has been returned. Juries decide guilt, judges mete out punishment.

Youth courts, which deal with defendants under the age of 18, are much less formal. Special panels of magistrates sit at them. The public is not allowed here, but journalists are. There is an automatic ban, in almost all cases, against naming not just the defendant, but any other young person involved in the proceedings, including witnesses. There are a number of strict rules as to what details you can give to avoid identifying them. You can’t name the school they go to, for example, or their parents, because that would make it very easy for them to be identified.

The vast majority of cases are tried at the magistrates' court. Only the relatively low number of more serious crimes go to crown court – and all of those begin at the magistrates'.

There are a number of essential facts you must get – and get absolutely right – when covering court. For anything but a very short report you will need:

- The defendant’s name and address, so that he or she is clearly identified

- Their marital status, family situation, age and job

- What they are charged with

- Any previous convictions

- The names of magistrates or judge, so you can attribute any quotes they give when passing sentence

- Any good quote given when passing sentence or during the case

- The names of prosecuting and defending lawyers, so you can attribute their quotes

- Any good quotes from them

- The names and addresses of witnesses

- Any good quotes from witnesses

- Anything said in mitigation by defence lawyers before sentence is passed

- The sentence.

Court cases follow a clear procedure. First the charges are read out and a plea is taken from the defendant – they say whether they are guilty or not guilty of those charges.

If they plead guilty, things are very straightforward. The prosecution outlines the nature of the offence, the defence speaks in mitigation, and the magistrates or judge decide upon the sentence.

If the plea is not guilty, then the prosecution outlines the case against the defendant. Witnesses are called and give their evidence. The defence may cross-examine those witnesses, seeking to test what they have said.

Once the prosecution case is completed, the defence mounts its case. It also calls witnesses, who can be cross-examined.

Then prosecution and defence make their closing speeches. At magistrates', they have only those court officials to convince. But at a crown court, before a jury, they will be seeking to persuade its members to go with their version of events. The judge will then give his or her own summing up, which is designed as guidance for the jury.

The jury then retires to consider its verdict. Once they have returned and delivered it, the judge passes sentence.

With short cases in the magistrates’ court, you are usually reporting the entire case in one report. In that case the report must be fair – give something from both sides.

But, if the case runs on, and you are reporting on it each day or even several times a day, you can only give an accurate summary of the segment you are reporting on in each online or print report. In that case, your duty of fairness means that, having reported on the prosecution’s case against the defendant, you are duty bound to give something of the defence’s answer to the case against them when it is presented. So, although reporters often don’t attend all of a long court case, they need to dip in and out at appropriate moments to keep their report balanced.

After the event

Once a verdict has been reached, there is no danger of us being in contempt of court, so we can run backgrounders, interviews and generally go to town on a person found guilty of a crime.

It’s ok now for readers or others to express their opinions of the person who has been found guilty. For instance, a beaten wife can now express the view of her husband as an evil sadist – if he has been found guilty.

It is ok to have comments online from readers and to discuss the case in forums.

Court reporting examples

Here are some typical magistrates court cases.

Here is one from the Hastings Observer. The case is a routine one of a person who steals from parked cars, but the punishment is unusual, and that’s what the report begins with:

Thief gets car park ban

"Magistrates slapped an unusual ASBO on prolific crook D----- N-----, 27, who admitted stealing from parked cars.”

"It prohibits him from setting foot in any public or private car park, with the threat of jail if he does."

Although the report is short and the accused admitted the charges, it still goes on to give something from his defence solicitor.

Here’s a court case from Lancaster Today. It’s a straightforward drink driving case except that a very young child was in the car:

Mum caught drink driving while picking daughter up from nursery

"A MORECAMBE mum was caught picking up her daughter from nursery while nearly four times over the drink-drive limit, a court heard."

In this case there is a good deal in the short report from the defence, because the reasons for the offence are what is interesting. The defendant is said to have been drinking the night before, not during the day, and had turned to alcohol to deal with a messy divorce and an abusive husband.

Magistrates' court cases are often very compelling little dramas. In a couple of hundred words you get a portrait of folly, loss, despair, greed or stupidity.

7B3 Developing your skills as an interviewer

Here is some guidance on interviewing.

A good interview is a good conversation, from the BBC:

How to conduct an interview with a source:

Katie Couric on how to interview:

How not to conduct an interview:

Beach rescue interview

So far, we have mostly dealt with situations where interviewing was only a small part of getting the story. Now we will look at a situation where, if you don’t get an interview, you will have very little to write. As we have mentioned before, stories often begin with a small piece of information – a tip from a contact, or a brief mention of an event. We often need to find someone to interview if we are to turn those brief mentions into full stories.

Here’s an example of a short post on an ambulance authority’s news wire, which you might have on an RSS feed.

Paramedics attend trapped boy on beach

At 13.21 hours yesterday an emergency call was received from the beach attendant on Echo Beach. The caller reported a child in difficulty. Two paramedics in a vehicle were dispatched from G Division headquarters and arrived at the scene at 13.47 hours.

On arrival at the scene the paramedics were directed towards a male child of four years of age who had got his head stuck between two rocks on the beach.

On examining the child the paramedics became aware that the child’s head was severely wedged into a recess between the rocks and could not be easily extracted.

At this point concerns were raised as the tide was encroaching on the boy and would reach him in a matter of minutes.

The paramedics proceeded to make efforts to extract the boy, but initial efforts involving manipulation were unsuccessful.

Observing that the child was becoming increasingly distressed, the paramedics resorted to sedating the child as his level of distress was impeding rescue efforts.

Once the child was calmed, paramedics were able to employ a sledge hammer and cold chisel to chip away at the rocks that were trapping him.

Concerns grew as the tide was now within centimetres of the boy and fast approaching. Only after prolonged chipping at the rock could the boy be freed.

He is now in Echo Beach hospital and is in a comfortable condition. He will be kept under observation overnight.

(The release ends with the name of the press contact, their direct line, mobile number and e-mail.)

What is missing from this account?

This is obviously a good rescue story, but the release gives very few of the details of the rescue. We don’t know who the boy is and, just as importantly, we have no quotes that will give us all the drama of the rescue.

We can write a news story now – and should do so – but more information is needed for a full story. Ideally, we need an interview with the victim’s parents and the child’s rescuers. The story could be told in text and stills, on video, in audio or in a combination of these four, depending on the access we get.

Perhaps there is video of the rescue, taken either by the emergency services or a bystander.

If you are lucky, the parents of the boy will agree to be interviewed by you with him. He is only four but he is old enough to say a little about what has happened to him. And if you can get the rescuers there as well this will add to the drama of the story.

Let’s imagine you are granted an interview, and look at how you should approach it.

Preparation

When you read about the story on the news wire, the first thing you did was call the press contact whose details were at the end of the release. You asked them to give you more information about the boy, the family, the rescuers and the incident. You found out the parents stayed with their son at the hospital overnight and are there now.

You asked the press officer if they could get the family’s permission for you to come and interview them. You got a lot of background from the press officer too.

About the family

The parents are Mr and Mrs John and Kay Smith and they live at 66 Star Road, Capital City, which is 20km away from Echo Beach. They are both 36 years old. Their son is called Jack and he will be five next month. He is their only child. The father works as a supervisor in a plastics factory, and the mother works part-time on a supermarket check out.

About the rescuers

The two paramedics were Jason Jones and Peter Round. Jason is 26 and is a senior paramedic in the Echo Beach ambulance service. Peter is 22 and recently completed his training. He is a junior paramedic and has been in the job for just six months. The beach attendant, Michael White, assisted by supplying tools.

How the accident came about

The parents say that it all happened very quickly. Police officers will be interviewing them tomorrow to find out more about the circumstances of the accident, but the press officer cannot give you any more information now.

All this is very useful. That means you don’t need to ask lots of basic routine questions when you meet the boy and his parents. If you don’t get such information in advance it is a very good idea to gather it off camera before you begin to film, otherwise your video will be full of detail that needs cutting, and that makes for a tricky editing job.

You need, in your interview with the parents, to concentrate on what happened and – most importantly – how they felt.

You need to be professional in your approach to a delicate interview like this.

You must show that you are anxious not to distress the boy. Reporters who show that they just want to get the story and run off will not find their interviewees very cooperative. And uncooperative interviewees won’t give you as good a story as those who trust you and are prepared to open up.

The interview

We need an interview that will work both as a text report, but also as a strong, succinct video report. As ever, you need to balance things so that you get the essential material on film.

Start with some simple questions off camera. Perhaps just confirm some basic details such as their names, ages, address, and other details you need such as what jobs the parents do.

Writing in a notebook can mean that you have your head down and are not looking at your interviewee. Try not to keep your head buried. Look up regularly, and nod or make other appropriate gestures and comments as they talk. It is important that they feel this is a conversation, or they may become reluctant to talk.

You need to get a fully rounded picture in your head of what happened. One good approach to doing that is to ask them to start at the beginning and go on from there.

If you take your interviewees through the story chronologically you will get that full picture, and be able to spot any gaps in your knowledge.

With the rescue story you would start with the parents, asking about events before they found their son was in danger. You can turn to the rescuers at the point when they arrive at the scene. From there you have a dual interview to manage. And, at the right moment, you will want to try to get some quotes from the young boy.

Be prepared to ask lots of questions before you start filming so that you have a mass of information from which to pick the very best points to address when the camera is rolling. Thin interviews produce thin stories.

With the parents you can ask them about their visit to the beach. Do they come often? When did they arrive this time? Get them talking about their day before the accident happened. Little of this makes good film, so it is worth getting out of the way.

As they answer your questions, other questions will occur to you. Without them realising it, and without it seeming forced, you can learn a lot about the family. If they break off from their chronological account, and tell you other interesting things, let them do so, but make sure you go back to the story at the point they left off, and get them to continue.

Now you are ready to film. Here’s the transcript of the video you shoot. Jack’s father does almost all the talking. His mother seems very upset.

It must have been a real ordeal for the family. How are you feeling now?

“Very, very relieved that Jack is ok. It could have been so much worse.”

Is Echo Beach somewhere you come often?

“Jack loved Echo Beach. Any time we had free and if the weather was good, we would take him there. He loved to play on the rocks. There are pools with little fish in them that he tried to catch with his hands.”

How did Jack get into difficulties? Had he wandered off?

“No. We could see Jack playing on the rocks just 10 metres away from us. There were several other children there too and an older girl was holding Jack’s hand. We were watching him carefully because the tide was coming in, and I was just getting up to bring him back when we saw him let go of the girl’s hand and slip. His head disappeared from view and his legs were waving in the air.”

What did you do?

“I ran as fast as I could down to him. When I got to him I saw his top half was down between two rocks.”

How did you realise he had got trapped?

“I took hold of his legs with one hand and reached down with the other under his chest – I was trying to lift him out.”

How was Jack at this point?

“He was very frightened. He was struggling and crying out. I told him not to worry and that we would soon get him out.”

“I shouted for help because there were only children around and I knew I could not free him on my own. The beach attendant ran over and between us we tried tugging and twisting Jack but it was no good.”

“Then the attendant took out his mobile phone and called 999.”

[to the ambulanceman] How was Jack when you got to him?

“Jack was very frightened. He wasn’t crying but he was very distressed and struggling violently. We talked to him and tried to pull him free, but we couldn’t.”

“The beach attendant told us he had a hammer and cold chisel in his workshop, and as the rock was soft sandstone we could chip away at it. I asked him to go and get the tools.”

“At this point I decided Jack needed to be sedated so that he would not struggle and be injured as we chipped away at the rock.”

“Once Jack was calm, I was able to shield his head with my hands while my Colleague Peter chipped the rock away. Within a few seconds I was able to lift Jack away from the rocks.”

“I was very relieved that we had been able to free him. The water was coming in fast and was only a few metres away. I dread to think what would have happened if we had got there 10 minutes later. He could have been drowned.”

Back to Jack’s father

What were you feeling as you saw the tide getting closer and closer?

“I was terrified. I really thought that Jack was going to drown. I was so scared and just didn’t know what to do. Once Jack was free I just hugged him so tight. We were all in tears and so relieved.”

How is Jack now?

“He’s still in shock we think. He isn’t saying much at all and he is very clingy, just hugging us all the time.”

Jack. Has it been a bit of an adventure?

Jack nods. “It was slippery and I fell. I was very scared but Jason got me out.”

Is there anything you’d like to say to Jason?

“Thank you very much for saving my life.”

What would you like to do when you go home?

“I’d like to have some ice cream.”

[Turning back to the parents]

Do you blame yourselves at all for what happened?

[Jack’s mother speaks for the first time] “I blame myself, I should never have let him go on the rocks on his own. What happened to Jack should be a warning to other parents. It could so easily have been so much worse. Jack could have died.”

Jack’s father adds

“We’d just like to thank Jason so much. He saved our little boy.”

Writing up the text report

The quotes we have make a comprehensive video report. If we have footage of the rescue we can intercut it with the audio track of the interview.

As we are focusing on text reporting in this chapter, let’s put a story together from the quotes and other information. Write a news story of between 300 and 400 words. Bear in mind that a brief news story has already appeared on your website, detailing the rescue. So what’s new? What’s new is that we have the interview, and Jack has met his rescuers.

Don’t read on until your version is complete. Here is our suggestion.

Head: Jack, 4, thanks rescuers who saved his life

Sell: A four-year-old boy rescued from drowning on Echo Beach has thanked the men who saved his life. More…

Jack Smith was playing at the beach when he fell and trapped his head between two rocks.

With the rising tide just metres away from him, paramedics Jason Jones and Peter Round chipped the sandstone away with a hammer and chisel to release the boy.

Jack, who became distressed during the rescue operation and had to be sedated to keep him calm, was taken to Echo Beach hospital overnight for observation.

Speaking at his bedside, his father John, of Star Road, Capital City said: “We’d just like to thank the Jason so much. He saved our little boy.”

Jack’s mother, Kay, added: “What happened to Jack should be a warning to other parents. It could so easily have been so much worse. Jack could have died.”

As for Jack, he said: “It was slippery and I fell. I was very scared but Jason got me out.”

Asked if he’d like to say anything to his rescuer, Jack said: “Thank you for saving my life.”

Jack was just metres away from them on the rocks, said his parents, when he fell. Beach attendant Michael White called the emergency services and, when it became clear the boy could not be freed by hand, ran to his workshop and fetched the tools with which he was cut free.

The rescue was a race against time as the waves were fast approaching the boy.

Mr Smith said: “I was terrified. I really thought that Jack was going to drown.”

Paramedic Jason Jones said: “I was very relieved that we had been able to free him. The water was coming in fast and was only a few metres away. I dread to think what would have happened if we had got there 10 minutes later. He could have been drowned.”