Chapter 1 – Genre and the organization of text

Activities and comments

Download All (PDF 243KB)(Activities that are asterisked are particularly useful for discussion in class, in which case multiple copies or PowerPoints of the text could be produced.)

Activity 1

- A strong earthquake struck western China on Monday morning.

- In western China a strong earthquake struck on Monday morning.

- On Monday morning a strong earthquake struck western China.

- Western China was struck by a strong earthquake.

- It was western China that was struck by a strong earthquake on Monday morning.

- It was on Monday morning that western China was struck by a strong earthquake.

- It was an earthquake that struck western China on Monday morning.

Which of the sentences above, 1–7, uttered with normal intonation, are the most appropriate answers to the following questions?

- On Monday morning western China was hit by floods, right?

- When did a strong earthquake strike western China?

- On Monday morning a strong earthquake struck Taiwan, didn’t it?

- What happened to western China?

- What happened on Monday morning?

We can see that the most important new information in answering question A is that it was an earthquake, not floods, that impacted western China. So (7) is the best answer as ‘an earthquake’ is emphasised by this structure.

The information required by B is about the time when the earthquake struck, so (1) would be the most straightforward reply, with ‘on Monday morning’ ending the rheme.

C assumes that Taiwan was hit by an earthquake, so (5), which contradicts this, would be best.

D already includes the given information that something happened to western China, so (4) would be a good answer with this information in the theme, and the new information in the rheme.

Similarly, E already includes the given information that something happened on Monday morning, so (3) would be a good answer, with this given information in the theme, and the new information in the rheme.

Activity 2

Look at the following extracts (slightly modified) from an abstract/summary of a mini-dissertation, and say what you think is wrong with them. How could you rewrite them to distribute given and new information better? (You can make a few adjustments by adding a word or two if necessary, as in examples 5–7, in Activity 1.)

ABSTRACT

- That persuasion depends on the interrelationships between discourse and society is generally recognised.

- The idea that ideological persuasion can be repeated, so that later it becomes taken for granted, is argued in this study.

- Essentially the framework for studying discourse proposed by Fairclough (1992) will be used.

We think A would be better rewritten as:

It is generally recognised that persuasion depends on interrelationships between discourse and society.

This is because the main focus of emphasis is not on the recognition of the fact, but on the fact itself, so putting ‘recognised’ at the end of the rheme seems awkward.

We think B would be better rewritten as:

In this study I argue that ideological persuasion can be repeated so that later it becomes taken for granted.

Putting ‘this study’ (and arguing) near the end of the rheme is not a natural choice, since we all know that this dissertation is a study of some kind, so this knowledge is certainly given information. And what is important is not the arguing itself but what is being argued.

We think C could be better rewritten as:

Essentially I will use the framework for studying discourse proposed by Fairclough (1992).

It is quite obvious that dissertations use theoretical frameworks, so emphasising this as new information is not appropriate. The writer may have taken to heart the maxim that academic writing should be impersonal, and this has driven her to use the passive voice. However, the desire for impersonality is probably outweighed by the need for smooth distribution of given and new information. If impersonality is insisted upon, then an alternative possibility would be:

Essentially this study will use the framework for studying discourse proposed by Fairclough (1992).

Activity 3

The following two paragraphs convey the same information but distribute it differently by having different themes. Identify the first themes of each sentence in both passages. Which passage is most successful, and how is this related to the patterning and progression of themes?

1.

Spring and fall are the most beautiful time of the year here in the Blue Mountains. Millions of wild flowers and trees are in bud, and the many planned gardens in the region start to flourish in springtime. The North American species of trees introduced long ago into the region – oak, elm, chestnut, beech and birch – do the same in the Blue Mountains as they would in the Catskills: turn brilliant reds, oranges and yellows in fall. Campers and hikers are found descending on the mountains in throngs in summer, and the mountains are at their quietest and most peaceful in winter, offering perfect solitude for city escapees.

2.

Spring and fall are the most beautiful time of the year here in the Blue Mountains. In springtime millions of wild flowers and trees are in bud, and the many planned gardens in the region start to flourish. In fall the North American species of trees introduced long ago into the region – oak, elm, chestnut, beech and birch – do the same in the Blue Mountains as they would in the Catskills: turn brilliant reds, oranges and yellows. Summer finds campers and hikers descending on the mountains in throngs. Winter is the time the mountains are at their quietest and most peaceful, offering perfect solitude for city escapees.

(Fodor’s Sydney p.115, quoted in C. Matthiessen (1992) ‘Interpreting the textual metafunction’, in M. Davies and L. Ravelli (eds), Advances in Systemic Linguistics. London: Pinter, pp. 37–81.)

Underlining indicates the themes of the sentences in the two passages. In (1) there is no particular pattern for the choice of theme, except that two out of the five themes refer to trees and flowers. By contrast, (2) shows a very tight control in the choice of themes, with all five referring to seasons. This makes (2) more successful.

TEXT 1.

Spring and fall are the most beautiful time of the year here in the Blue Mountains. Millions of wild flowers and trees are in bud, and the many planned gardens in the region start to flourish in springtime. The North American species of trees introduced long ago into the region – oak, elm, chestnut, beech and birch – do the same in the Blue Mountains as they would in the Catskills: turn brilliant reds oranges and yellows in fall. Campers and hikers are found descending on the mountains in throngs in summer. The mountains are at their quietest and most peaceful in winter, offering perfect solitude for city escapees.

TEXT 2.

Spring and fall are the most beautiful time of the year here in the Blue Mountains. In springtime millions of wild flowers and trees are in bud, and the many planned gardens in the region start to flourish. In fall the North American species of trees introduced long ago into the region – oak, elm, chestnut, beech and birch – do the same in the Blue Mountains as they would in the Catskills: turn brilliant reds, oranges and yellows. Summer finds campers and hikers descending on the mountains in throngs. Winter is the time the mountains are at their quietest and most peaceful, offering perfect solitude for city escapees.

*Activity 4*

Find a short paragraph from a book or magazine text that is written in continuous prose. Try to analyse it by seeing what kinds of paragraph structure it incorporates. Remember that most real paragraphs will mix at least two of the basic designs – step, stack, chain and balance. How useful are Nash’s categories of paragraph type?

Activity 5

Which of the following genres is generally deductive, point first, and which inductive, point last: murder mystery; research article; classified advert; sophisticated advert in a glossy magazine; joke; news report?

Murder mysteries, jokes and sophisticated commercial adverts are invariably inductive; classified adverts and news reports are deductive; research articles are a mixture – insofar as their main point is made in the results or conclusion sections, which appear last, they are basically inductive, but insofar as they announce their findings in the abstract, which comes first, they are to some extent deductive.

Activity 6

Look at the following short narrative. Try to identify the narrative moves Abstract, Orientation, Complicating Action, Resolution, Coda and Evaluation.

I think Peter’s always been a bit foolhardy. I remember once we were on holiday in Cornwall, and it was one of those lovely sunny breezy days which are just right for a picnic. So we’d decided to go down to Clodgy point, the rocky cliffs of the Atlantic coast. After picnic lunch Peter and his brother asked if they could go for a walk while me and my husband had a nap. So off they went. They hadn’t come back in two hours, so we went to look for them. We walked quickly along the cliff for half an hour, and, as we came round a promontory we caught sight of them at the foot of the cliff on the rocks at the opposite side of the cove. I was terrified. How had they got down there? We called frantically for them to come back. They climbed up the steep grassy slope, which must have been about 60 degrees. I don’t know how they did it. When they met us at the top I said,

‘Why did you go down there? Don’t you know it’s dangerous?’

Peter held out a black and white striped snail shell, and all he said was,

‘If we hadn’t gone down there I would never have seen this.’

So nowadays I’m never surprised to hear he's involved in some dangerous adventure or other.

Probably the narrative can be divided into the following sections.

ABSTRACT I think Peter’s always been a bit foolhardy (The point of the story.)

ORIENTATION I remember once we were on holiday in Cornwall, and it was one of those lovely sunny breezy days which are just right for a picnic. So we’d decided to go down to Clodgy point, the rocky cliffs of the Atlantic coast. (Setting the scene; no simple past tenses except with stative/relational verbs.)

COMPLICATING ACTION (the succession of narrative clauses in past tense describing a sequence of events). After picnic lunch Peter and his brother asked if they could go for a walk while me and my husband had a nap. So off they went. [EVALUATION They hadn’t come back in two hours (negative)], so we went to look for them. We walked quickly along

the cliff for half an hour, and, as we came round a promontory we caught sight of them at the foot of the cliff on the rocks at the opposite side of the cove. [EVALUATION I was terrified (comment by narrator). How had they got down there? (question)] We called frantically for them to come back. They climbed up the steep grassy slope, [EVALUATION which must have been about 60 degrees (modal clause). I don't know how they did it (negative, comment by narrator).] When they met us at the top I said,

[EVALUATION ‘Why did you go down there? Don’t you know it’s dangerous?’ (questions, evaluative comment by character/narrator)]

RESOLUTION Peter held out a black and white striped snail shell, and all he said was, [EVALUATION ‘If we hadn’t gone down there I would never have seen this.’ (negative, modals)]

CODA So nowadays I’m never surprised to hear he’s involved in some dangerous adventure or other. (Brings us out of the narrative by the time reference nowadays, and the tense, present.)

Activity 7

Look at the news report about Christopher Reeve already used in the introduction. Sentences are numbered for your convenience.

‘Superman’ may never walk again

SUPERMAN star Christopher Reeve is in hospital with a suspected broken back (1). His family ordered hospital officials not to give out any information – but sources say he is partially paralysed (2).

The actor’s publicist, Lisa Kastelere, was plainly upset as she revealed that horse-mad Reeve was hurt show-jumping in Virginia (3).

Witnesses saw him hit the ground hard as his horse shied (4). As doctors evaluated his condition in the acute care ward at the University of Virginia’s Medical Center in Charlottesville, it was not known whether he will walk again (5).

Reeve, 43 and 6ft 4in, was flown to the hospital by air-ambulance after doctors at the competition decided he needed special care (6).

Reeve, who starred in 4 Superman movies, lived with his British lover Gael Exton for 11 years (7). They had two children (8).

Reeve then began a relationship with singer Dana Morosini (9).

- Can you identify the different elements of Van Dijk’s model in that text?

- *Experiment with modifying this for an online newspaper with hyperlinks and new generic elements.

‘Superman’ may never walk again [HEADLINE]

SUPERMAN star Christopher Reeve is in hospital with a suspected broken back (1). [LEAD/MAIN EVENT]

His family ordered hospital officials not to give out any information – but sources say he is partially paralysed (2). [VERBAL REACTION]

The actor’s publicist, Lisa Kastelere, was plainly upset [REACTION] as she revealed that horse-mad Reeve was hurt show-jumping in Virginia [VERBAL REACTION [EVALUATION] [BACKGROUND]] (3).

Witnesses saw him hit the ground hard as his horse shied (4). [BACKGROUND]

As doctors evaluated his condition [REACTION] in the acute care ward at the University of Virginia’s Medical Center in Charlottesville [BACKGROUND], it was not known whether he will walk again (5). [COMMENT]

Reeve, 43 and 6ft 4in, was flown to the hospital by air-ambulance after doctors at the competition decided he needed special care (6). [REACTION]

Reeve, who starred in 4 Superman movies, lived with his British lover Gael Exton for 11 years (7). They had two children (8).

Reeve then began a relationship with singer Dana Morosini (9). [BACKGROUND]

*Activity 8*

A. Which of the following discourse types or genres would you regard as most visually informative? List them in order of informativeness. *You might bring an example into class and be prepared to identify the kinds of visual informativeness it displays.

- poem

- form

- recipe

- textbook

- magazine advert

- newspaper report

B. Does your ranking of the different text types tell anything about the degree to which the readership for these is assured?

A. Poems are generally not very informative, except for the spacing between stanzas, capitalisation of initial letter of the line, and line endings. Of course there are experiments with concrete poetry, e.g. a poem about a snake in the shape of a snake, and kinetic poetry, but these are unconventional.

Textbooks no doubt vary but are probably the next least visual. They will probably have (numbered) headings which will be highlighted in some way, and use bullets and enumeration, especially in summary sections. Psychology textbooks seem to be more visual than others, often using columns and varying fonts.

Recipes often have two sections, one for ingredients, one for the cooking instructions; these may be distinguished visually in blocks separated by white space. The separate ingredients are listed on separate lines, though this is not always the case with the steps in the cooking procedure, unfortunately – see the example of the Step. Do you ever forget where you are up to?

Newspapers usually use columns; their headlines and sometimes the first paragraph (lead) are in larger font; and they will often have sub-headings, bolded and boxed insets of extracts from the main article, etc.

Forms make liberal use of white space, boxes, different colours, bullets, enumerative devices, arrows, bolding, variation in font and font size and so on.

Magazine advertisements will usually have coloured pictures, which occupy at least 60 per cent of their area. They tend to employ many different fonts in different sizes, and may exploit the whole range of graphical resources mentioned above.

B. In some cases assuredness does seem to be an explanatory factor. For example, poetry readers are generally pretty much assured, or the poet has a take-it-or-leave-it attitude. And this would explain why newspapers are more visually informative than textbooks; students are either motivated or forced to study their books, but newspaper readers are much more selective in the articles they read. Cooks need recipes, and are not planning to give up halfway through cooking, so they can be relatively uninformative visually.

Forms seem to be the main exception here. Generally, one has no choice in filling in a form. But precisely because many are designed for all sections of the population, of varying degrees of literacy and education, bureaucrats have been forced to make them as filler-friendly as possible. Perhaps taking an assured readership for granted is no excuse for being visually mean; a richly visual textbook may well fulfil its purpose or convey its content more effectively, even if the readership is in any case motivated to keep reading.

Activity 9

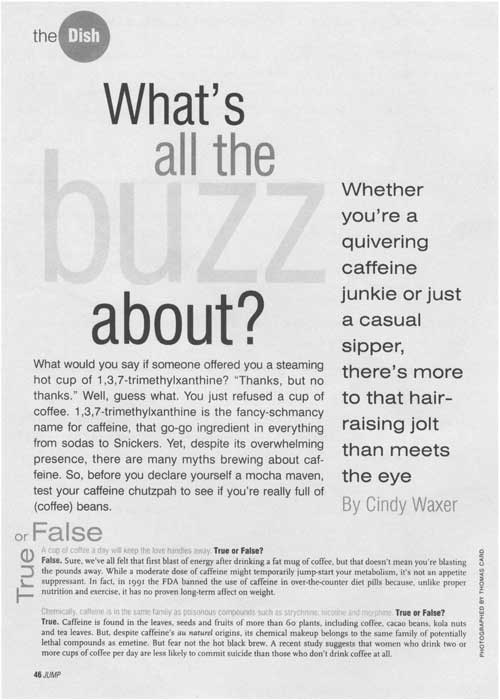

- Compare the email from Education and Curricular Review (EDCR) with ‘What’s all the buzz about’ (WB), both below. In what ways do these two texts differ in their global layout features (2), use graphics to make textual organisation clear (3), or use local text features or highlighting (4)? Which of the two texts is more visually informative (1)?

- Word-process the email from Education and Curricular Review to make it more visually informative, like the WB feature on coffee

Three New Book Reviews from Educational and Curricular Review>

Educational and Curricular Review, a Journal of Book and Curricula Reviews in Education

[EDCREV@abc.edu] on behalf of Jean Smith [smith@abc.edu]

Sent: Wednesday, July 09, 2014 3:57 AM

To: EDCREV@abc.edu

The Educational and Curricular Review is an open access (‘free-to-read’) journal that has published more than 3,200 reviews of books and Curricula in education continuously since 2001. The Educational and Curricular Review has just published three new book reviews.

- Toubro, Mariam C. & Lock, Smith B. (2014). Streamlining Design: A Practical Guide to Design for Instruction. NY: ABC Books. Reviewed by Alicia Defenter

- Chacko, Arthur M. (2015). Personalized Instruction: Pathways Designed by Students in High School Education. CA: Erwin Press. Reviewed by Anne Black, Bradon, LT & Andrew McNeil, Bedford, NH

- Kumari, Aditi. (2014). Mediating Curriculum with Inquiry-based Learning. New York, New York: Agave McNeilson. Reviewed by Rochelle L. Bloomsbury, Bovine Central University

These reviews can be accessed at http://www.edcrev.info

- Joseph J. Whittier, Editor for English

- Bernado Pinto, Editor for Spanish & Portuguese

- Martha Brendon, Co-Editor for English

- Jean Smith, Executive Editor

Education and Curricular Review/Reseñas Educativas y los del Plan de Estudios is a project of the College of Education and Human Services of the University of Delmonte, the Mary Lowe Fulbright Teachers College, Arabia Central University, and the National Educational Curricular Planning Center.

Follow Education Review on Facebook at http://tinyurl.com/27jtg7d and on Twitter @EducCrlReview

_____________________________________

[To be removed from this mailing list, email listserv@abc.edu with the message UNSUB EDCREV.]

WB seems more visually informative. Under (1) WB uses the precariously balanced text to grab the attention.

Under (2) EDCR only uses white space as allowed by the email program, indentation of reviewed items and paragraphing, but WB uses columns for the titles, white space to localise each true/false segment, vertical orientation for ‘True’, variable indentation for the main title, and some lettering on dark background, and various colours (though this is not apparent from the black-and-white reproduction).

As for type (3) features, neither text is especially visual.

In terms of (4), EDRC uses only one font type, Times New Roman, and does not vary size in the email itself, and only highlights through italics and bullet points. WB uses at least two different fonts, in six or seven different sizes, and uses bolding.

*Activity 10*

Promotional emails are commonplace in the internet age. Take a look at one such visually informative email and identify the various clusters, explain their specific meanings, and see how they relate to the overall purpose of the email.

*Activity 11*

Take the following text, which has a discourse structure typical of narrative, and transform it into a news report (200–250 words).

- Concentrate on reproducing the typical discourse structure of a news report in a quality online newspaper, including as many of the generic elements as possible, in an appropriate order. Indicate how the different parts of your text realise these categories. You may have to invent some material, especially for the consequences and comment categories and hyperlinks, and, of course, you do not have to include all the details of the original. Verbal reactions may be added and become more important, as it is only through these that the reporter can access the thoughts and feelings of a character.

- You should also modify other aspects of style besides discourse structure. Typical news report features include placing together (or apposition) of two phrases referring to the same person, e.g. ‘Janet Lee 32, a receptionist with Peat Marwick’; inclusion of detailed precise facts like ages or exact numbers; complicated noun phrases, e.g. ‘the judge in the mail train robbery trial in Aylesbury’; and short paragraphs of one or two sentences. Look at a few newspaper reports as models.

- Make your text more visually informative and multimodal than the original, in ways that are appropriate to news reports.

- Be prepared to discuss the changes that have been made to the discourse structure and visuals of the original narrative. Why does the new discourse structure seem inappropriate for this material? Does this story contain the news values necessary for newsworthiness?

- How could you have given a different emphasis and a different value to the news reported by selecting a different headline and lead for your story?

Little Red Ridinghood

Little Red Riding Hood’s mother was packing a basket with eggs and butter and home-made bread.

‘Who is that for?’ asked Little Red Riding Hood.

‘For Grandma,’ said Mother. ‘She has not been feeling well.’

Grandma lived alone in a cottage in the middle of a wood.

‘I will take it to her,’ said Little Red Riding Hood.

‘Make sure you go straight to the cottage,’ said Mother as she waved good-bye, ‘and do not talk to any strangers.’

Little Red Riding Hood meant to go straight to the cottage, but there were so many wild flowers growing in the wood, she decided to stop and pick some for Grandma. Grandma liked flowers. They would cheer her up.

‘Good morning!’ said a voice near her elbow. It was a wolf. ‘Where are you taking these goodies?’

‘I’m taking them to my Grandma,’ said Little Red Riding Hood, quite forgetting what her mother had said about talking to strangers.

‘Lucky Grandma,’ said the wolf. ‘Where does she live?’

‘In the cottage in the middle of the wood,’ said Little Red Riding Hood.

‘Be sure to pick her a nice BIG bunch of flowers,’ said the wolf and hurried away.

The wolf went straight to Grandma’s cottage and knocked at the door.

‘Who is there?’ called Grandma.

‘It is I, Little Red Riding Hood,’ replied the wolf in a ‘little girl’ voice.

‘Then lift up the latch and come in,’ called Grandma.

Grandma screamed loudly when she saw the wolf’s face peering around the door. He was licking his lips. She jumped out of bed and tried to hide in the cupboard, but the wolf, who was very hungry, caught her and in three gulps ate her all up. Then he picked up her frilly bedcap that had fallen to the floor and put it on his own head. He pushed his ears inside her cap, climbed into Grandma’s bed, pulled up the bedclothes and waited for Red Riding Hood to come. Presently, there was a knock on the door.

‘Who is there?’ he called, in a voice that sounded like Grandma’s.

‘It is I, Little Red Riding Hood.’

‘Then lift up the latch and come in.’ She opened the door and went in.

‘Are you feeling better, Grandma?’ she asked.

‘Yes dear, I am. Let me see what you have in the basket.’ As the wolf leaned forward the bedcap slipped and one of his ears popped out.

‘What big ears you have,’ said Little Red Riding Hood.

‘All the better to hear you with,’ said the wolf, turning towards her.

‘What big eyes you have Grandma!’

‘All the better to see you with,’ said the wolf, with a big grin.

‘What big teeth you have!’

‘All the better to eat you with!’ said the wolf and threw back the covers and jumped out of bed.

‘You are not my Grandma!’ she screamed.

‘No I’m not. I’m the big bad wolf,’ growled the wolf in his own voice, ‘and I’m going to eat you up.’

‘Help! Help!’ shouted Little Red Riding Hood as the wolf chased her out of the cottage and into the wood.

The woodcutter heard her screams and came to the rescue. As soon as the wolf saw the woodcutter’s big wood-cutting axe, he put his tail between his legs and ran away as fast as he could.

‘What a lucky escape I had,’ said Red Riding Hood to the woodcutter.

What a lucky escape indeed.

Quiz

Further Reading

Further reading for Chapter 1

- Halliday and Matthiessen chapter 3, Downing and Locke chapter 6, and Eggins chapter 9 all provide a comprehensive account of the grammar of theme and rheme. Butt chapter 6 gives a simpler version. Eggins units 2 and 3 are a clear and detailed account of the theory of genre and register; and Butt et al. deal with the same concept in a very simplified way in chapter 8.

- Butt, D. (2000). Using Functional Grammar: An Explorer’s Guide (2nd edn). Sydney: National Centre for English Language Teaching and Research.

- Downing, A. and Locke, P. (2006). English Grammar: A University Course (2nd edn). London: Routledge.

- Eggins, S. (2004). An Introduction to Systemic Functional Linguistics (2nd edn). New York and London: Continuum.

- Halliday, M.A.K. and Mathiessen, C. (2004). An Introduction to Functional Grammar (3rd edn). London: Hodder.

- Halliday and Hasan’s Language Context and Text chapter 4 explains the idea of generic structure and gives clear examples of how it is related to social context. Tony Bex’s Variety in Written English provides a useful overview of written genres.

- Halliday, M.A.K. and Hasan, R. (1989). Language, Context, and Text: Aspects of Language in a Social-Semiotic Perspective (2nd edn). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bex, T. (1996). Variety in Written English: Texts in Society: Societies in Text. London: Routledge.

- Walter Nash’s Designs in Prose chapter 1, pp. 9–19,is the source for the accounts of paragraph structure given in this unit. Although, or because, most of his examples are made up, they are often humorous and entertaining. This book has been perhaps superseded by Nash and Stacey’s Creating Texts: An Introduction to the Study of Composition. Both are very useful rhetorical manuals, though they have little to say about the ideological dimensions of texts.

- Nash, W. (1980). Designs in Prose: A Study of Compositional Problems and Methods. Harlow: Longman.

- Nash, W. and Stacey, D. (2014). Creating Texts: An Introduction to the Study of Composition. London: Routledge.

- Colomb and Williams’ ‘Perceiving structure in professional prose’ is a very useful article. It is the source for the point-first and point-last distinction, but elaborates many other aspects of prose structure, such as the way texts hang together through lexical patterning to form discourse units of various extents.

- Colomb, G.G. and Williams, J.M. (1985). ‘Perceiving structure in professional prose: a multiply determined experience’, in L. Odell and D. Goswami (eds), Writing in Non-Academic Settings. New York: Guilford Press, pp. 87–128.

- Stephen Bernhardt’s ‘Text structure and graphic design: the visible design’ is the source for the features of visual informativeness mentioned in this unit. It makes an interesting comparison between grammatical/lexical features of texts and their visual equivalents, within a functional framework. Parts of Goodman and Graddol’s Redesigning English have interesting work on the visual aspects of texts.

- Bernhardt, S. (1985). ‘Text structure and graphic design: the visible design’, in D. Benson and J. Greaves (eds), Systemic Perspectives on Discourse, vol.2. Norwood NJ: Ablex.

- Graddol, D., Goodman, S. & Lillis, T.M. (eds). (2007). Redesigning English. London: Routledge.

- Ronald Carter and Walter Nash’s Seeing through Language chapter 3 is a useful exploration of narrative structure, as is chapter 18 of Montgomery et al.’s Ways of Reading. William Labov’s original account of the structure of oral narratives can be found in Language in the Inner City. The major introduction to narrative is Michael Toolan’s Narrative: A Critical Linguistic Introduction.

- Carter, R. and Nash, W. (1990). Seeing Through Language: A Guide to Styles of English Writing. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Montgomery, M., Durant, A., Fabb, N., Furniss, T. and Mills, S. (2007). Ways of Reading: Advanced Reading Skills for Students of English Literature (3rd edn). London: Routledge.

- Labov, W. (1972). Language in the Inner City. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Toolan, M. (2012). Narrative: A Critical Linguistic Introduction. London: Routledge.

- Van Dijk’s ‘News schemata’, from which the model of generic structure of news reports is taken, has an extremely interesting later section which explores convincingly the ideological potential of news structures.

- Van Dijk, T.A. (1986). ‘News schemata’, in C.R. Cooper and S. Greenbaum (eds), Studying Writing: Linguistic Approaches. London: Sage, pp. 155–185.

- There is a considerable literature on genre and its teaching, mainly within an Australian context. Most useful and accessible for the teacher are Brian Paltridge’s Genre and the Language Learning Classroom, and Frances Christie and Jim Martin’s Genre and Institutions: Social Processes in the Workplace and School. The latter includes a chapter by Peter White most relevant to this unit ‘Death, disruption and the moral order: the narrative impulse in mass-media “hard news” reporting’ discussing how aspects of narrative influence the genre of news reports.

- Paltridge, B. (2001). Genre and the Language Learning Classroom. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

- Christie, F. and Martin, J.R. (eds). (2005). Genre and Institutions: Social Processes in the Workplace and School. London: Continuum

- Gunther Kress explains key concepts in multimodality or visual informativeness of texts in this great collection of videos. Each video focuses on a particular set of questions and key concepts and provides clearer understanding of visual information of texts and its related issues.

- Kress, G. (2012). ‘Key Concepts in Multimodality’ Retrieved 25 October 2015, from http://mode.ioe.ac.uk/2012/02/16/video-resource-key-concepts-in-multimodality/

- Martin and Bednarek’s New Discourse on Language presents innovative analyses of multimodal discourse, identity and affiliation within functional linguistics. In chapter 4, Knox et al. present a detailed analysis of two Thai newspapers by looking into various aspects of language, images and page design to show how social bonds are developed and maintained between newspapers and their readers.

- Knox, J.S., Patpong, P. and Piriyasilpa, Y. (2010). ‘Khao naa nung: a multimodal analysis of Thai-language newspaper front page’, in J. Martin and M. Bednarek (eds), New Discourse on Language. New York and London: Continuum.

- Baldry and Thibault’s Multimodal Transcription and Text Analysis analyses and interprets a range of multimodal texts and genres in relation to their social and cultural contexts. Concepts such as ‘clusters’ and the ‘resource integration principle’ and their application to a variety of texts can be found in chapter 1. Chapter 3 looks in detail at webpages and how the technological resources of the web allow hypertext pathways that link webpages and websites in complex ways.

- Baldry, A. and Thibault, P.J. (2006). Multimodal Transcription and Text Analysis: A Multimedia Toolkit and Coursebook. Oakville, CT and London: Equinox.

- The following article gives some insights on how headlines and leads are selected and manufactured according to their importance.

- Baxter, C. (2012). ‘What do subeditors do?’ Guardian. www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2012/jul/26/subeditor-role-changed, retrieved 18 October 2015