Selected highlights

Introduction

This web page contains a collection of stories, insights, examples, exercises, tips and key points from the four different books. They illustrate certain themes that are important to the possibility of Living Confidently with Specific Learning Difficulties (SpLDs).

The icons used are:

- story

- insight

- example

- exercise

- tip

- key point

In the books, the key point icon is that of the relevant chapter.

The book icons and page numbers indicate where highlights come from. Book 1 pages refer to the revised edition.

The text is true to that in the books, which alters who ‘you’ addresses:

- ‘you’, the reader, is a dyslexic/ SpLD person in books 1 and 2

- ‘you’, the reader, is someone helping a dyslexic/ SpLD person in books 3 and 4 and may or may not be a dyslexic/ SpLD person.

A small number of changes are enclosed in brackets [..].

Some selections include references to other places in the book in question. If you want to follow the reference, go to the page the box comes from and you will find the page number of the reference. There are a few references to books outside this series; the reference details will be at the end of the chapter that the highlight is taken from.

When present the narrator is Ginny Stacey. CloseLabelling

Introduction

These highlights show some of the issues to do with using labels for SpLDs.

They help when their use leads to dyslexic/ SpLD people being enabled.

They don’t help if they are used as excuses or reasons to lower expectations.

Acceptance with problem solving p 76

Story: Acceptance, with problem-solving

When I taught a group of dyslexic students at university, they complained that they couldn’t use dyslexia as an excuse with me, because I’d just say, “OK. Let’s find the way round that, then.”

Dyslexic passenger p 145

Story: A dyslexic passenger

One student knew he was dyslexic at a young age. He’d had support at school. He was good at sport and had a confident, cheerful outlook on life. He continued support at university. I was aware that he wasn’t gaining anything useful from the support sessions with me.

I gave him an overview of the effects of dyslexia and how to deal with it. I told him nothing would develop in his mind until he could see it was relevant to him. I told him coming to support was a waste of his time until he wanted to make progress. We kept the lines of communication open.

He eventually came back saying my comments had made him reflect. He realised he hadn’t put any effort into learning as a child; he’d used dyslexia as an excuse; he’d gone to the support sessions as a passenger.

He had treated support at university in the same way: as a passenger. He has now recognised the impact of his dyslexia and comes for support with a readiness to develop skills. He even wants to learn how the English language works. He felt my comments were the first time he’d been challenged to face up to his dyslexia and deal with it.

Not told as child p 132

Story: Not told as a child

Sam was in his fourth and final year of a degree course when he first came for support.

He had been assessed while still at school. So his parents had known he was dyslexic since he was 15. They didn't tell him the result of the assessment because they were afraid he would use it as an excuse and not continue working. Sam thinks they were right at that time of his life.

He struggled in the first years of his university degree, which is often the case even when someone knows they are dyslexic. He didn’t really communicate his struggles to his parents and so it wasn’t until partway through his third year that anybody thought the way he was struggling had anything to do with dyslexia or that there might be effective solutions to his problems.

Sam acknowledged that he had effectively wasted 2½ years struggling when he could have been learning how to manage his dyslexia effectively.

Don't worry, we know you can't do this p 59

Story: Don’t worry, we know you can’t do this

One student needed help with writing a major report. We went through the standard collection of received wisdom for dealing with major projects. We used different types of technology, programs and recording devices. We drew up plans for the report, timetables and various lists for dealing with all aspects of getting the report written.

She was making a little bit of progress. There were many issues to do with the work that had gone wrong and which undermined her writing fluency.

She was dyslexic and known to have mental health problems.

There was one session at which she had decided to face up to the enormous task she was trying to complete. Gradually we could see that she was crippled by the legacy of kindly meant reactions from her childhood: “Don’t worry, we know you can’t do this.”

She has a deep-seated belief that she can’t do anything and any time there was a difficulty with her writing, this belief got activated. It is so deep it is going to take this student many years to be free of its influence.

The people in her childhood were doing the best they could, but the outcome was far from good and a huge burden for the student.

Story: Best case scenario: good techniques, minimal dyslexia p 156

Story: Best case scenario: good techniques, minimal dyslexia

One student was doing a vacation job for a few weeks alongside me.

I observed her ways of working for several weeks. She had many strategies that dyslexic students use but didn’t seem to have any dyslexic problems.

I asked if she were dyslexic. She told me that she had a few quirky spellings, but she knew what they were. She explained that her mother was a specialist teacher for dyslexics and that her mother had recognised the early symptoms of problems and had taught her how to overcome them right from the start.

This student enjoyed all the riches of her strategies and thinking preferences without experiencing most of the problems, and without being bothered by those she did have.

The gift of your understanding p 56

Key point: The gift of your understanding

When you understand more about the problems dyslexic/ SpLD people have with gaining knowledge and skills, you lift a layer of burden from them. They no longer have to explain their ways of doing anything or justify them. They can get on with finding the solutions that allow them to gain knowledge and skills to the best of their abilities and then to contribute to society to their full potential.

SpLD experience-language

Introduction

One of the joys of working with a group of dyslexic/ SpLD people is that they hear each other’s stories and experience. They begin to feel they are in good company; they take each other’s experience seriously; they can laugh with each other. They also see a bigger picture and realise there are so many differences in the range of experiences that this group of people have.

Non-dyslexic/ SpLD people often say that the stories are similar to their experiences. When they listen more deeply, they appreciate that there is an extra element from the dyslexia/ SpLD.

This selection tells some SpLD experiences with language.

CloseSet in stone, Sleep is not doing p 50 ( p 89)

Insight: Set in stone

Story: Sleeping is not doing

Insight: Children are told early on that ‘verbs are doing words’, and they are taught the patterns of verbs using doing words. ‘Verbs are doing words’ becomes the oldest memory trace that can’t be modified.

Story: One dyslexic student objected, “Sleeping is not doing; it cannot be a verb.”

Mal-sequencing in spellin p 99

Story: Mal-sequencing in spelling

Michael Newby (1995) persuaded Tim Miles [editor of a book]that some spelling errors were mal-sequencing, or mistiming, rather than not knowing how to spell a word.

Certainly many students have described their writing problems as the mind racing ahead with thoughts while the hand lags behind.

The result is often that words the mind is thinking about get written into the text the hand is writing and the words look jumbled up.

Not finding words p 107

Story: Not finding words

In a group of dyslexics, person A was giving directions to B. It was a conversation, but neither was using words very well. They were using hands and diagrams to ‘speak’ to each other. At one point the rest burst into laughter. “You aren’t using words! But B knows where to go!”

Diplomacy can be hard p 349

Insight: Diplomacy can be hard

Some dyslexic/ SpLD find it quite hard to be diplomatic. The thought of writing extra words is not a good one; several of us wish others wouldn’t be so WORDY! Our succinct way of expressing ourselves can be misinterpreted as unsociable, unfriendly or undiplomatic.

SpLD Experience – observation

Introduction

One of the joys of working with a group of dyslexic/ SpLD people is that they hear each other’s stories and experience. They begin to feel they are in good company; they take each other’s experience seriously; they can laugh with each other. They also see a bigger picture and realise there are so many differences in the range of experiences that this group of people have.

Non-dyslexic/ SpLD people often say that the stories are similar to their experiences. When they listen more deeply, they appreciate that there is an extra element from the dyslexia/ SpLD.

This selection is about SpLD experience and objective observation.

CloseYou have to listen to yourself p 47

Insight: You have to listen to yourself

Dyslexic/ SpLD people do not all process information in the same way, for example:

- some dyslexic people use mind maps very well, others can’t use them

- some remember very well what they have done, others remember what matters to other people (for other ways people remember well and think well, see Thinking Preferences)

nor is the problem presented necessarily the one that needs to be addressed:

- One student asked for help writing her essay; she just couldn’t find her usual fluency. Everything I suggested, she either had tried, or she came back with a reason why it wouldn’t work. She kept repeating the word, “Can’t”.

We brainstormed around ‘Can’t’. She was a mature student, several hundreds of miles from home during the week and her teenage daughter was at home with her husband. It wasn’t working for the daughter to be so far from Mum and the worry was undermining the mother’s management of her dyslexia.

Once she recognised the problem and what needed to be done, her language fluency returned and there was no problem with writing.

Noticing curious behaviour p 116

Story: Noticing curious behaviour

Often groups of students live together in a house. They select their group because they all get on well together. One student in such a group came to ask to be assessed for dyslexia. The others in her house were dyslexic and already putting together ways to manage their dyslexic traits. They had watched her using the same kinds of strategies so then they all discussed the problems they faced. The others were convinced she was also dyslexic and that their shared experiences were why they all got on. On assessment, she also turned out to be dyslexic.

SpLD experience – pitfalls

Introduction

One of the joys of working with a group of dyslexic/ SpLD people is that they hear each other’s stories and experience. They begin to feel they are in good company; they take each other’s experience seriously; they can laugh with each other. They also see a bigger picture and realise there are so many differences in the range of experiences that this group of people have.

Non-dyslexic/ SpLD people often say that the stories are similar to their experiences. When they listen more deeply, they appreciate that there is an extra element from the dyslexia/ SpLD.

This selection is about the impacts of dyslexic/ SpLD pitfalls.

CloseImportance of pitfalls p 73

Key point: The importance of Pitfalls

It is the way we, the dyslexic/ SpLD community, get tripped into dyslexic/ SpLD functioning that makes PITFALLS so important.

Glitches p 74

Examples: Glitches

Introducing someone by the wrong name, e.g. Champion for Campbell because both start with C and are linked in your mind, but noticing it immediately and then using the correct surname.

Saying, “The dyslexic person beside me needs some food now.” Then recognising you should have said “diabetic person” and correcting immediately.

It is the immediate correction that contains the pitfall as a glitch and prevents it becoming more of a problem.

To London for a cup of coffee p 122

Story: To London for a cup of coffee

One student was settling down to write his essay, and decided a cup of coffee would help. He found he’d run out of coffee, so he went down the corridor to borrow some from a friend. As the friend was out, he decided to go to the local shop and get some. The coach for London was picking up passengers outside the shop. So he got on and went to London.

Take everything just in case p 43

Insight: Taking everything, just in case

Many dyslexic/ SpLD people end up taking everything because they cannot be sure what they will need for the day and they know that they will not be able to do tasks without the necessary equipment.

The effort to arrive at precisely the right time p 49

Story: The effort to arrive at precisely the wrong time

One student discovered that the more she tried the worse the problems became and the more people emphasised any complications the more difficulty she had.

On one occasion, a tutor stressed that he had to go to a meeting at 3pm, so he would have time to see her at 2pm. The stress on ‘3pm’ eclipsed the session start at 2pm.

The student was very pleased with herself to arrive exactly at 3pm; she had taken a lot of trouble to get herself there on time, to no avail.

Fighting against sleep while reading p 252

Key point: Fighting against sleep while reading

I have learnt to recognise that fighting against sleep while trying to read means that I am not processing properly the material that I am reading; I have to look for something that is not being solved by [my reading strategies]:

- the author’s style may be wrong for me

- the grammar may be ambiguous

- negatives can be used in a complicated way

- there may be unfamiliar words, or unfamiliar use of words

- I may have questions about the background

- my mind can be engaged on another topic

- other.

A few of the dyslexic/ SpLD difficulties while driving p 486

Key points: A few of the dyslexic/ SpLD difficulties while driving

- You know the directions spatially, but don’t reliably say left and right correctly.

- You can’t concentrate long enough to take in the directions.

- You don’t remember to organise the route in advance.

- You don’t hear the words correctly when given directions.

- You transpose the road numbers; you transpose letters or words.

- You don’t mentally process the sequence of different directions.

- You don’t process what you see on the road signs quickly enough to take the appropriate action.

SpLD experience – thinking

Introduction

One of the joys of working with a group of dyslexic/ SpLD people is that they hear each other’s stories and experience. They begin to feel they are in good company; they take each other’s experience seriously; they can laugh with each other. They also see a bigger picture and realise there are so many differences in the range of experiences that this group of people have.

Non-dyslexic/ SpLD people often say that the stories are similar to their experiences. When they listen more deeply, they appreciate that there is an extra element from the dyslexia/ SpLD.

This selection is about the importance of knowing what thoughts are happening, or not.

CloseNot realising what you are doing p 175 p 86

Story: Not realising what you are doing

“You are so busy asking the question, you don’t realise that’s what you are doing” is the way one of my dyslexic colleagues describes her lack of grasp of what is happening when she is using words.

Changed perspective 3: "I got one spelling right!" p 90

Story: Changed perspective 3: “I got one spelling right!”

A teacher was looking at some work with Lucy and commenting on the spelling. Lucy had spelt one particular word many different ways, including one that was right.

Lucy’s tactic was to use as many different versions in the hopes that one would be right.

The teacher was puzzled by the variety and said to her, “Look you’ve got it right here, so why didn’t you get it right every time?”

Lucy, internally, was gleeful and thinking, “Yes, I got it right once!”

The external and internal views about the spelling were so different that there was no discussion about it, nor any development of spelling strategies; so Lucy made no progress from the conversation.

This story is not an unusual one. It shows a behavioural outcome from Learned Confusion, p 44.

Which SpLD is behind poor notes? p 98

Example: Which SpLD is behind poor notes?

Writing notes can be necessary:

- in many jobs

- for students

- to take telephone messages.

Among the reasons for poor notes are:

- dyslexia: not being able to spell words

- dyspraxia: fatigue setting in when writing; badly written words

- AD(H)D: lack of attention means there are gaps in the information.

Out of sight is out of mind p 48 p 90 p 110

Insight: Out of sight is out of mind

There are many times that I’ve discussed how easily SpLD people don’t remember anything that is out of view.

The situations include:

- of a pile of books or papers, only the top one can be thought about

- difficulty in remembering information on one website in order to work with it on another website; both need to be completely in view

- ideas for a big project have to be spread out so that they are all in view together.

"Meet you at the top of the road" p 367

Story: “Meet you at the top of the road”

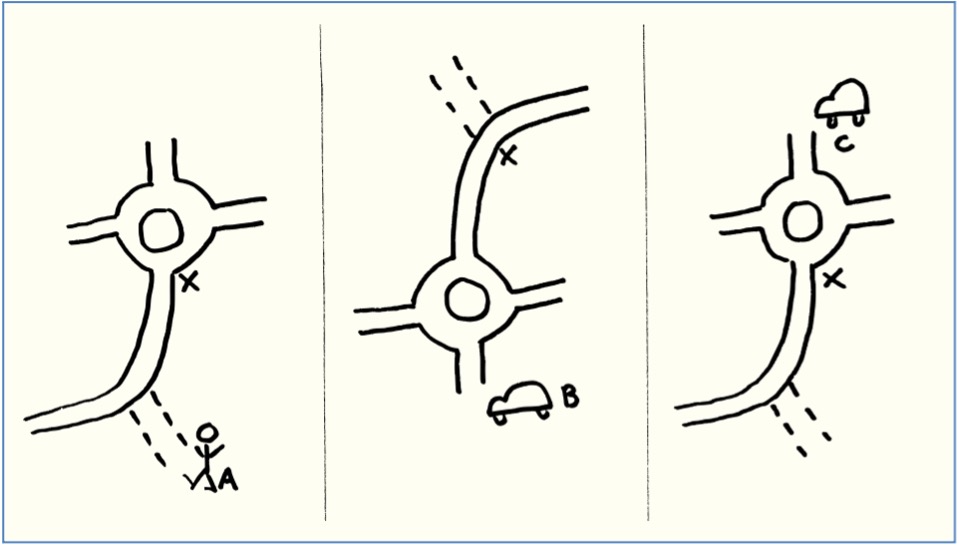

Two people A and B have agreed to meet “at the top of the road”. A is walking along a path to the road. B is coming to the road from a roundabout. They have to agree a time for meeting because parking is difficult. B was quite frustrated when he had to wait a long time for A. Since this happened several times during a week, they decided to compare what they meant by “the top of the road”.

Figure 1 Where is the top of the road?

X marks the top of the road for the 3 people A, B and C

A and B have internal, mental maps with themselves at the bottom, at the point where they enter the road; which is why they wait for each other for ages.

B told the story to C and discovered that in C’s internal map she is at the top of her map, again where she enters the road. She would have met with A as soon as they have both arrived.

Episodic memory remaining whole p 156

Key point: Episodic memory remaining whole

[Episodic] memory becomes a problem for dyslexic/ SpLD people if they cannot break the experience into smaller units, for example many dyslexic/ SpLD people can’t break up the alphabet song to find out where a letter is. Some have to start at ‘a’ and sing the song until they get to the letter; some know roughly where the letter is and can start a little bit before, and then they sing the song until they get to the letter they want.

No amount of using the song this way allows them to learn where the individual letters are in the alphabet.

Senses not working together p 122

Insight: Senses not working together

The senses may not work together for some dyslexic/ SpLD people.

I went to an outdoor concert of Handel’s Music for the Royal Fireworks accompanied by a fireworks display. I found I could watch the fireworks, in which case I didn’t hear the music, or I could watch the musicians in which case I heard the music but was unaware of the fireworks.

I have mentioned this in talks about dyslexia/ SpLD and found others experience the same thing. One person said:

“You mean you’re supposed to be able to hear and see together?”

I have also discovered that closing my eyes changes the way sound comes to me: with eyes closed it is all around me, with eyes open watching a performer, the music is less in volume and restricted to the performer.

Others have reported similar reactions.

Mind and hand out of sync p 96

Insight: Mind and hand out of sync

Students have reported that their minds are racing on with their ideas while the hand is dragging behind; they find words belonging to ideas in the mind get written in amongst the words that the hand is trying to write. Fast touch-typists should have less of a problem with this than slow typists or those who write by hand. To be a fast touch-typist many of the movements will have been learnt to the point at which they become automatic and the typing process will be much better able to keep up with the production of ideas.

A good sentence lost p 129 p 164

Insight: A good sentence lost

I discuss phrasing of ideas with students. Many times one of us will say a sentence that captures an idea very well. We try to write it down straight away but neither of us can remember what it was.

SpLD experience – time

Introduction

One of the joys of working with a group of dyslexic/ SpLD people is that they hear each other’s stories and experience. They begin to feel they are in good company; they take each other’s experience seriously; they can laugh with each other. They also see a bigger picture and realise there are so many differences in the range of experiences that this group of people have.

Non-dyslexic/ SpLD people often say that the stories are similar to their experiences. When they listen more deeply, they appreciate that there is an extra element from the dyslexia/ SpLD.

This selection tells some SpLD experiences of time problems.

CloseTime words have no meaning p 91

Story: Time words have no meaning

One lad kept missing evenings out with friends. They would all agree something like, “See you at 8 o’clock”. He would even check that he was free. The connection that was missing was: 8 o’clock was only an hour after dinner time and that the diary entry ‘dinner with Matt’ meant he was unlikely to be free at 8 o’clock.

Similar but different things kept happening to him. None of the solutions he tried worked until he saw that he was not really thinking about time, even when he was talking sensibly about it.

Problems with co-ordinating time p 92

Examples: Problems with co-ordinating time

- People will leave one place at the time they should arrive for a meeting, lecture, etc.: a meeting starts at 10, or the coach to London leaves at 10, and you leave the house at 10.

- Sometimes, it is only as you leave for an event, or just as an event starts, that you remember details and know about another collection of items you should have taken with you.

- You don’t remember what you have to do at a useful time; you remember when you can’t do anything about it.

I want to be early for once p 270

Story: I want to be there early for once

2 friends went to a birthday party together. They arranged to go in one car.

The driver emphasised that she wanted to be early and to arrive before 6pm. She said she’d pick her dyslexic friend up an hour earlier, at 5.

When she arrived at 5pm, the dyslexic wasn’t remotely ready, thinking there was still an hour left before the car owner would arrive.

So they were unhappy and late.

The emphasis on arriving early made 6pm the important time.

When it comes to getting ready, the important time is when to start getting ready, so 6pm had become the time to start getting ready.

I never start on time p 422

Story: I never start on time

One student came and said he could never start at the time he wanted to and that he wasn’t getting enough revision time. He was getting depressed about his late starts and therefore not working well.

When we did a very detailed look at his timetable for the day, he realised he wasn’t putting in time to eat breakfast and that eating breakfast made him start revision later than he planned.

Once he put in time for breakfast and was no longer starting later than he expected, his revision went well.

SpLD experience – space, place and direction

Introduction

One of the joys of working with a group of dyslexic/ SpLD people is that they hear each other’s stories and experience. They begin to feel they are in good company; they take each other’s experience seriously; they can laugh with each other. They also see a bigger picture and realise there are so many differences in the range of experiences that this group of people have.

Non-dyslexic/ SpLD people often say that the stories are similar to their experiences. When they listen more deeply, they appreciate that there is an extra element from the dyslexia/ SpLD.

This selection shows space, place and direction play a part in SpLD experiences.

CloseThe same behavioural difficulty from three SpLDs' perspectives p 255

Example: The same behavioural difficulty from three SpLDs’ perspectives

Take a difficulty with direction:

A dyspraxic person may have no sense of direction because their body is not giving them clear signals and there is confusion in the mind about direction.

A dyslexic person can know the directions quite clearly but not be able to verbally label them so they can still have a problem with direction and communicating direction.

A person with AD(H)D might have problems with direction because they can never pay attention for long enough to get a clear picture in their mind of where things are.

The source of the problem is quite different although to the outsider the behaviour may seem very similar.

An inconsistent memory for space and direction p 109

Story: An inconsistent memory for space and direction

A manager frequently had to direct visitors to the office of the next person the visitor was going to see. The manager’s memory for the route depended on the way she was facing. She could remember details of corridors and spaces in the direction that she was facing, but if the route for the visitor turned a corner, she had no memory of what came next unless she turned to face the new direction. But as she turned for the new direction, she lost her memory of the route she’d just described. So to describe a complete route, she had to keep turning herself with every turn of the route.

SpLD tactics

Introduction

This groups is a small sample showing some of the many different ways people deal with their dyslexia/ SpLD.

CloseClothes for the week p 99

Story: Clothes for the week

One headmistress set out all the clothes she would wear during a week every Sunday, so that choosing what to wear didn’t add an extra task to the morning.

Ideas lead, words follow p 370

Insight: Ideas lead, words follow

I find that when I focus on the ideas I want to talk about, I can leave the words to follow. I don’t get distracted because I can’t think of the best word or a word that is hovering on the edge of my conscious mind.

My way of focusing on ideas involves my Thinking Preferences. I will frequently use the situation or student who first showed me the importance of the topic I’m talking about. My notes will contain a reference to the person or situation, rather than a wordy description of the idea I want to put across.

Architecture in mind maps p 314

Story: Architecture in mind maps

One student put a whole year’s architecture modules in mind maps that he put on his walls. He found he had to remember only one key idea on each map and then he could remember all the rest of the map.

Calligraphy pen to distinguish importance p 178

Tip: Calligraphy pen to distinguish importance

One practical tip for distinguishing main themes from detail while taking notes is to find a calligraphy pen, a fibre tip one which has two different thicknesses. Important points are written with the thick side, the others are written with the narrower side. Your student is actively assessing the importance of information as she writes, which helps her to make the decision.

Distant deadlines p 188

Story: Distant deadlines

One person had three deadlines all in one week which was several months away.

We had a single calendar sheet which went from the present day to the last of the deadlines. When we put in her lectures, her holidays, some family events and calculated the amount of time she had for each deadline, she found she had just three weeks for each of the deadlines.

Realising how little time she had gave her the motivation to work seriously even though each deadline was several months away.

The look of the printed page p 123

Tip: The look of the printed page

The visual aspects of the printed page can make a difference in so many different ways:

- the colour of paper

- the colour and contrast of computer screens

- the font used

- italics may not be read as easily as normal

- full justification distorts the words or their relative position

- hyphens can help or hinder.

Using punctuation p 256

Story: Using punctuation to read

One student used the punctuation to help her read aloud while recording herself. She didn’t try to understand what she was reading. She used the punctuation to modulate her voice, so that it became softer at the end of phrases and sentences.

She then listened to her recording. The rise and fall of her voice helped her to understand what she was listening to. For her, this was much more satisfactory than re-reading a passage several times and still not understanding. It was better than reading aloud on its own because she could go back over any passage if necessary.

Notes that are for your student p 303

Key point: Notes that are for your student

Notes are often a private affair, reminding your student of some ideas. She can mis-spell to her heart’s delight; she can use symbols rather than words; she can show relationships between ideas by the way she uses the space around the words; she has to worry about neatness only in so far as it matters to her.

Managing SpLD – strategies

Introduction

Dyslexia/ SpLD are syndromes for which there is no cure. Even when a person has learnt how to deal with many of the effects, there is always the potential to find oneself in a situation when all the coping strategies have evaporated because a dyslexic/ SpLD pitfall has come your way.

Managing dyslexia/ SpLD is a combination of knowing what works best for you, the individual, most of the time and how to deal with pitfalls when they occur.

This selection highlights some issues about strategies.

CloseIndividual profile develops over time p 65

Insight: Individual profiles develop over time

A profile [of dyslexia/ SpLD – strengths, strategies, pitfalls] is unlikely to be fixed for all time. You can get to a stage where your profile serves you well in most of your life and then you find a new task or situation is bringing back dyslexic/ SpLD problems again. You should go back to exploring your profile and see what you need to add to cope with the new situation or task.

Add the new insights to your profile.

Mental energy reserved for monitoring p 127

Insight: Mental energy reserved for monitoring

Some part of [your] mental capacity has to be alert for problems, especially in meetings or exams and similar situations.

Remembering the system p 174

Insight: Remembering the system

If [your student] needs to use a specific pattern, encourage her to record it in some way and some place so that she doesn’t forget her decision. It is quite easy to design a system one day, forget what it was and design another the next day and end up confused between the two systems.

Knowing the goal p 181

Key point: Knowing the goal

The final element in your student’s Regime for Managing Dyslexia/ SpLD is to know her goal in any task. In using knowledge and skills your student is aiming to achieve a particular result, or several results. If she is very clear about what she wants to achieve, she is more likely to stay on task and be able to minimise the effects of her dyslexia/ SpLD.

What is your goal? p 79

The previous Key Point: Knowing The Goal applies to many situations or tasks. This exercise is a good way to recognize your goal.

Exercise: What is your goal?

You have paused to manage a situation or task.

What is the task facing you? or the situation?

What do you want to do?

How much time do you have?

What resources do you have?

Define your goal as clearly as possible.

What Pitfall has caused you to pause? Is it a hazard or an obstacle?

How do you want to cope with it?

How is it impacting on your goal?

What is the next step for achieving your goal?

Your student understanding her own notes p 308

Key point: Your student understanding her own notes

There is often a time issue about remembering what the notes mean.

- Many dyslexic/ SpLD people recognise that there is a limited period of time during which they can remember what the notes meant and what else was being discussed at the same time.

- If the notes were made to be used later, it is important that they are re-drafted while they can still be understood.

- Students either need to add to the original set or they need to re-make the notes in a way that will make sense after some considerable time.

At this point it is probably worth your student getting the spelling right, so that she produces the correct words in her work. She can still use symbols and space to convey meaning, and she need only worry about neatness if the notes are to be shared with others.

Choice of job p 505

Key point: Choice of job and avoiding dyslexia/ SpLD

- The effects of dyslexia/ SpLD could well be magnified, if your student chooses a job that she is uninterested in but which she hopes will not challenge her dyslexia/ SpLD.

- A job that interests her is likely to help her manage her dyslexia/ SpLD, see Dyslexia/ SpLD and Interesting Jobs.

Managing SpLD – pitfalls

Introduction

Dyslexia/ SpLD are syndromes for which there is no cure. Even when a person has learnt how to deal with many of the effects, there is always the potential to find oneself in a situation when all the coping strategies have evaporated because a dyslexic/ SpLD pitfall has come your way.

Managing dyslexia/ SpLD is a combination of knowing what works best for you, the individual, most of the time and how to deal with pitfalls when they occur.

This selection highlights some issues about pitfalls.

CloseThe art of managing is to diminish pitfalls p 69

Insight: The art of managing is to diminish pitfalls

The more you inspect the pitfalls of your profile, the more you learn how to deal with them.

Recognising pitfalls p 76

Tip: Recognising pitfalls

As you observe objectively, you will be able to describe pitfalls that occur for you in terms of:

- any dyslexia/ SpLD issues

- what you notice as advance warnings

- any reactions in your body

- other signs you come to know.

Add anything useful to the pitfall section of your profile.

Be selective of ideas from others p 176

Tip: Be selective of ideas from others

Don’t expect other dyslexic/ SpLDs’ solutions to become yours; don’t adopt them without testing whether they will work for you. Other people’s strengths could be quite different from yours, and their strategies may not work at all for you.

Pay attention to newness p 52

Tip: Pay attention to newness

This insight applies to any first time event that might be repeated several times.

It is worth getting the way you deal with the situation right for you at the start of the event. It is often difficult or impossible to delete any errors from your memory by getting the processes right on the second run through. See the Index for other discussion about aspects of ‘new’.

Boring, safe options are dangerous p 68

Insight: Boring, safe options are unsafe

The other (external source of stress) is trying to avoid the effects of dyslexia/ SpLD by opting for a less interesting job or hobby; doing so can be counterproductive and increase levels of stress.

Because you are not interested, your mind will not be using interest to chunk information together and the capacity of working memory will not be enhanced; as a result, the effects of your dyslexia/ SpLD can become worse, and will not be avoided.

By contrast, an interesting job or hobby can minimise the effects of dyslexia/ SpLD. Tackling tasks that are difficult or especially challenging for you can be empowering. You are more likely to bring something special to the job or hobby. Other people are more likely to be supportive when they can appreciate and value your different contribution.

Policy

Introduction

The approaches that are VITAL for dyslexic/SpLD people to learn well and function using their best potential are good practice for everyone; it’s just that they are not necessary for other people.

This selection includes the benefit of others knowing the impacts of dyslexia/ SpLD and enabling the dyslexic/ SpLD people to use the processes that help them function well.

A key theme is that the right policies and approaches in education and society at large would reduce the financial and emotional cost of dyslexia/ SpLD.

CloseFor policy-makers and general readers p 495

Key points: For policy-makers and general readers

- Policies need to incorporate the good practices that are VITAL for dyslexic/ SpLD people.

Key general principles are:

- an openness that accepts differences easily

- clarity of expression

- a basic understanding of the difficulties from dyslexia/ SpLD and the solutions

- accommodations to meet the needs of dyslexic/ SpLD people when their own strategies can’t provide solutions.

A little good help early prevents a large need later p 157

Key point: A little good help early prevents a large need later

It is worth remembering that a small amount of effort and resources used early will save a great deal of effort and resources later on.

It is very much less wearying to have co‑operative children than ones who are fighting you every day of their childhood.

Why waste human beings or money? p 132

Key point: Why waste human beings or money?

The GOOD PRACTICE proposed should increase satisfaction and human potential and reduce costs, both financial and resource.

Group leaders and enabling dyslexic/ SpLDs p 460

Key points: Group leaders and enabling dyslexic/ SpLDs

- Put practices in place that accommodate some key needs:

- paperwork well in advance so that it can be read

- clarity in documents

- all information about a meeting kept together, even when only one detail is changed

- timing set out clearly.

- Check for possible misunderstanding.

- Leave material and information visible as long as possible.

- Allow time for dyslexic/ SpLDs to collect their thoughts.

- Understand the problems that could arise.

- Observe what happens.

- Assist when asked, without patronising.

- Reduce stress or tension in any situation.

Employers missing good employees p 442

Key point: Employers missing good employees

Employers should be aware that psychometric tests are ruling out some candidates who would have much to offer as employees.

For certain dyslexic/ SpLD people, asking them to succeed in psychometric tests is like asking a wheelchair user to go up a steep flight of stairs: practically impossible.

Employer reaction p 212

Insight: Employer reaction

One dyslexic person was in a job for several months before mentioning that she was dyslexic. She asked her employer whether he would have given her the job if he had known. His reply was: “No, I wouldn’t have done, but I am glad that I did.”

Someone knows about dyslexia p 120

Story: Someone knows about dyslexia

At my first role as university support tutor, the students had to fill in a form to request exam provisions every time they had exams. The exams office were frustrated that the forms from dyslexic students were so badly filled in. I told them to put example answers on the back of the letter that went with the exams form. I stressed that the students needed to see the blank form and the answers at the same time, otherwise there would be no improvement. The forms were then filled-in correctly.

One student told me the example being on the back of the letter told her that someone in the university knew the problems of dyslexia. The knowledge reassured her to the point that she relaxed about her difficulties and found her own ways round them.

Assessment test sidestepped p 199

Story: Assessment test sidestepped

“Well! He (the psychologist) said I’m dyslexic. It makes sense of quite a few things and he explained some issues to me. But he said the digit span [a test that is frequently used to assess auditory memory] showed I had a good auditory memory. And in my head, I saw my hand as I imagined writing the numbers as he said them and I read them from the picture. To read them backwards, I just read in the opposite direction. That’s not verbal. I can’t do it without picturing it.”

Thinking preferences

Introduction

This selection contains stories showing people using different ways to think and how it is possible to explore the ways people think.

CloseFeynman on testing thinking p 202

Story: Feynman on testing thinking

Richard Feynman, who won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1965, describes how he found out about his thinking in What Do You Care What Other People Think? Further Adventures of a Curious Character (Feynman, 1988).

He wanted to know how accurately he could count 60 seconds. (He was accurate at 48 secs.) As a result of his experiments, he found out how he did the task.

After he talked to colleagues about his experiments, one of them repeated the trials. They found that his colleague did the same task in a completely different way. Feynman was talking to himself; his colleague was watching a tape with numbers on it going by.

Feynman wrote:

‘We discovered that you can externally and objectively test how the brain works; you don’t have to ask the person how he counts and rely on his own observations of himself; instead, you observe what he can and can’t do while he counts. The test is absolute. There’s no way to beat it; no way to fake it.’

Thinking preferences and 5 objects to remember p 156

Insight: Thinking preferences and 5 objects to remember

You have been asked to take a collection of objects to a meeting and for other people to use, say a tape measure, a pair of scissors, a camera, tea bags and cake.

You could:

1) make a list |

verbal thinking |

2) picture all the items |

visual thinking |

3) know there are 5 in the list |

‘other’: it works, but I don’t know where to put it! |

4) run a video in your mind |

visualisation |

5) weave a story of the items being used |

interpersonal (MI) |

6) remember the reason for the items |

rationale |

These are just a few of the ways that you could use. The skill is to know the style that works for you, and to develop it to be really good. Be confident in your chosen style.

Know Your Own Mind exercise from a workshop p 194

Example: Mind exercise from a workshop

Contributions from [4] people were as follows:

RED: sun, Barcelona, car, fruit, wine, warm, happy, cotton rep

STAR: Christmas, money, family, wine, tree, presents, music

RED: ketchup, blood, Santa Claus, tomato, sea, pen, pepper

STAR: starry night, twinkle twinkle, starfish, brittle star, Southern Cross, star-crossed lovers, star student

The first RED came from a person who was seeing one particular holiday; the implication was that she was using the visual memory and episodic memory.

The person centring on STAR visualised herself in a scenario; she was remembering the situation in a way which showed a tendency for visualisation with kinaesthetic memory.

The second RED collection of ideas came from a person who was using visualisation, with taste where food was concerned.

The second STAR collection of ideas was triggered by songs, or verbal association with the word ‘star’.

No one size suits all p 196

Insight: No one size suits all

There are stories of the response, “You’re dyslexic, you must like mind maps,” to the deep irritation of those dyslexics for whom mind maps are anathema.

Variations in thinking preferences p 180

Example: Variations in Thinking Preferences

One person could

- perceive information from experience

- understand it by using a mind map

- start memorising it through the logical connections on the mind map.

While another person could

- perceive information visually

- understand it by making a list of keywords

- start memorising it through the rehearsal of the keywords.

A spanner in the notes p 197

Story: A spanner in the notes

One student came to me, for the first time, just before he had to do a presentation. We discussed his thinking preferences and how he was making his notes. He stopped making verbal notes for his presentation, because we had decided he was a visual thinker, and he drew his notes. A week later he came back with a grin on his face; he said that his conclusion was a drawing of a spanner. He looked at the spanner, knew what it meant; he looked his audience in the eye, and he “socked it to them”.

Memory recall triggered by movement p 157

Story: Memory recall triggered by movement

One successful company executive could never remember whether she had put the milk back in the fridge at the end of the day; the question would surface in her mind just as she was dropping off to sleep and then, whether she got up to check or not, going to sleep became difficult. She was a kinaesthetic thinker; she found that if she made some bizarre movement as she put the milk away, a different one every night, she could think of the movement, remember the milk going into the fridge, and go to sleep.

Physical energy used to sort out ideas p 206

Insight: Physical energy used to sort out thinking

[A colleague] wrote:

Some highly intelligent, kinaesthetic thinkers find their thought processes are sabotaged by sitting at a desk. They need to think by doing something quite physical and feel their thoughts through their bodies; it is as if their learning percolates by doing.

One client, who is extraordinarily gifted, goes on his bike when he wants to crystallise complex ideas and decide how he will convey them to others. He says his “gut gets it, understands it, but only by doing can I formulate and execute – I don’t have a picture or the words, but I know it’s there. It needs to grow, – and it can’t; sitting at my desk or in my office just does my head in”.

Adding kinaesthetic sense p 312

Examples: Adding kinaesthetic sense

One person liked gym. She would actually do cartwheels while working on one part of a subject, headstands on another, somersaults on a third, etc. Then in exams she just remembered the movement used while making notes and revising and all the information came to her mind.

Others take their notes for a walk, usually on a route they know well. They then mentally attach information from the notes to different objects along the walk: trees, gate posts, bus stops, etc. To recall the information they mentally go along the route to find it. The initial walk can be real or imaginary.

Rooms or places can be used in the same way to create a holding system for information. Changing the season or the decoration can be a way of expanding the possibilities. [Roman orators used this scheme.]

Make up a Story shows how one student linked marketing information to an imaginary walk. It is another example of adding the kinaesthetic sense to notes.

Processing skills – techniques

Introduction

There are a range of processing skills that help dyslexic/ SPLD people to use their minds more effectively. The ones highlighted here are about learning techniques.

CloseUsing mind set p 153

Tip: Using mind set

Mind set can be done by any method that gets you actively thinking about the task, or subject, that you are about to engage with:

- brainstorm: get down on paper everything you know about it, or dictate to a recording device

- make a mind map

- create a drawing or diagram that contains what you know or are interested in

- recap the last meeting, lecture, event or whatever is closest to the task in hand

- look up technical, or jargon, words used; get correct pronunciation.

Explore some useful questions:

- Why am I involved with this event/ studying this subject?

- What ideas are being discussed?

- What does anyone think is important?

- What is the scheme of the event/ framework of the subject?

Mind set extras for reading a book: pick up key ideas by looking at

contents, glossary, index, preface, covers,

chapter headings, summaries, tables, pictures, diagrams.

Analogy for mind set p 152

Insight: Analogy for mind set

Imagine going into a dark cottage, in the country, on a moonless night with the light switch the other side of the room: you will bump into furniture and anything else, you may fall over, you will move slowly and carefully across the room feeling for the light switch when you get to the other side.

But if you switch on a torch, you can walk confidently over to the light switch.

This analogy shows the difference between starting a new task with your mind switched off and with it switched on.

Mind set the evening before a day's revision p 418

Insight: Mind set the evening before a day’s revision

When there is a full day of revision planned, some people use the evening before to do mind set tasks in preparation for the next day. The mind set tasks might be something like organising the notes for the subject or finding the past papers or getting the textbooks together. It is often a related task but one which doesn’t make heavy demands on your student’s mental energies.

Chunking p 107

Tip: Chunking

Chunking is the process of making connections, or links, between pieces of information so that more is stored in each chunk and the capacity of working memory can be expanded.

Aids for concentration p 173

Tips: Aids for concentration

- Some find their concentration is improved by having music on.

- Some find breaks, going for a walk or run, are useful ways to refocus when concentration has been broken.

- For others, the break needs to engage the mind at the same intellectual level, e.g. by playing the violin, so that the mind is diverted, given a break but still intellectually active.

What goes wrong is useful p 54

Insight: What goes wrong is useful

Although I use visual thinking preferences very well on many occasions, I can’t use Post-it reminders the same way that others can.

Many people put notices to themselves where they will see them at strategic moments: e.g. notes stuck on the door to see as they go out of the house.

I don’t ‘see’ such notes; I have to put the notes where they will be in my way, so that they obstruct my physical movements; that way they work for me.

This pattern shows me that what I do (moving over the Post-its) is more powerful than what I see. I need to focus on using my kinaesthetic sense.

Remembering and positive concept p 159

Tip: Remembering and positive concept

To use the positive concept of remembering rather than the negative one of forgetting can be an important shift. Try thinking “I must remember ...” rather than “I mustn’t forget ...” and even “I won’t remember that!” is more useful than “I’ll forget that!”

Transferring skills from one task to another p 151

Example: Transferring skills from one task to another

On the football pitch, you learn to focus your mind where it is going to help you play, on:

your position, where opponents are, where the ball is, where your team mates are, how you are playing.

You try to ignore:

comments from the crowd, photographers near the pitch, aggravation from opponents or crowd.

Once you have the skill to focus your mind on football, you can transfer the skill to help with reading; you focus on:

what you want to know, what the author thinks are the key points.

You ignore: information that is not important to you, any thoughts that take you away from the ideas you want to get from the reading.

Thinking processes for plumbing job p 167

Example: Thinking processes for plumbing job - highlighted in orange

Plumber setting about a new job: ‘What’s needed to do a job?’

To describe the situation: The plumber is an operative within a small plumbing business which has office staff and a manager. The plumber will be given details of work, with client information.

I am assuming the plumber has the skills and training for the job.

He needs to check the paperwork is complete, that he understands what the client wants. He needs to organise the paperwork so that he can find it when he needs it and record information that the office will need for invoicing purposes, or further discussion with the client.

He needs to assess how long the job will take, when he is likely to get to the site and at what point (in time) he needs to tell the client, or office, that he is likely to get there.

He should decide whether he needs to investigate the job first in order to know what materials to use.

He will need to maintain his standard van stock as well as to order and collect any materials specific to the job.

With everything to hand, he can carry out the job.

Thinking processes p 173

The example highlight above has thinking processes picked out in orange; look at it before doing this exercise.

Exercise for student: Thinking processes

Reflect on a couple of situations you deal with regularly and decide what thinking processes are involved.

Use the patterns from Example Boxes: Thinking Processes for Plumbing Job, for Household Decision, for Coursework.

Write down what happens in the situations that you have chosen and then highlight all the thinking processes you are using.

Processing skills – language

Introduction

There are a range of processing skills that help dyslexic/ SPLD people to use their minds more effectively. The ones highlighted here relate to using language.

CloseAn aside about language interpretations by dyslexic/ SpLDs p 227

Insight: An aside about language interpretation by dyslexic/ SpLDs

It was very interesting teaching a group of dyslexic/ SpLD people. I knew that the way they interpreted what I said could be quite different and you could hear the differences in how they spoke:

- some would almost repeat my words

- some would be describing a picture in their heads, as observers

- some would be relating the conversation to themselves

- some would come back with an analysis of the ideas

- some would go off at tangents prompted by what I had said.

It was quite possible that none of us would remember my exact words, so any checking about the relationship between their thinking and what I had actually said would not happen without my visual teaching aids!

Reading meaningful groups of words p 187

Example: Reading meaningful groups of words

If the sentence

Harry had to go to the beach shop to buy his basket ball and spades.

is read with the following groupings:

Harry had to go to the beach shop to buy

his basket ball and spades.

the initial idea, ‘Harry had’, is one of possession, which starts the mind with the wrong expectation.

If the child’s mind is struggling to make the letters on a page into words he can sound, he won’t have enough working memory to store the words long enough to change his interpretation. Gradually, the whole passage becomes meaningless.

He needs to learn to group words in a more meaningful way:

Harry had to go to the beach shop to buy his basket ball and spades.

Main and second idea in a paragraph p 250

Exercise for students: Main and second idea in a paragraph

Read G9 - The Short Story: Paper on the template section of the website.

It has 4 paragraphs:

1) the first group of sentences

2) the next pair of sentences

3) and 4) the last two are obvious paragraphs.

What is the main theme of each paragraph?

What is the second theme?

Complex negative p 257

Example: Complex negative

Two statements from a questionnaire demonstrate complex negatives:

1

I have been fascinated with the dancing of flames in a fireplace. TRUE / FALSE

You picture the flames in your favourite fireplace and give the answer: TRUE

2

The warmth of an open fireplace hasn’t especially calmed me. TRUE / FALSE

You see yourself by a fireplace, relaxed, at ease with the world and answer: TRUE

BUT there’s a negative in there (The warmth... hasn’t ...calmed me.’), so the picture you’ve imagined is contrary to the statement. The answer for you is: FALSE.Learning

Introduction

The challenge of learning is often when dyslexia and dyscalculia first become an issue. Dyspraxia and AD(H)D may be noticeable before formal learning, but they also affect a person’s learning.

This selection highlights a few of the techniques which are really helpful and some of the stories about attitudes towards learning.

CloseWho eats the apple? p 43 p 143

Story: Who eats the apple?

One school-teacher friend used to ask his children, “If you are hungry and there’s an apple on the table, is it any good if I eat the apple?” “No, sir.” “Learning is the same: it’s your brain that has to do it.”

Pupil reluctance p 172

Story: Pupil reluctance

Hugo was 10 years old when he started receiving support. He was new to the idea that there were other ways of learning and, initially he was suspicious of some of the techniques. The teacher didn’t think that he really believed they would work.

They started with a target of learning how to spell some of the fairly short high‑frequency words that cannot be taught by using phonics, e.g. said, many, piece, etc.

So, on the ground they lined up as many footballs as there were letters in the word, i.e. 4 for ‘said’, 5 for ‘piece’. He would shout out the word and then as he kicked each football as hard as he could, he said the name of the letter; so in auditory terms, it would sound like “said, S, kick, A, kick, I, kick, D, kick”.

They continued to go through this five‑minute routine every day until they had covered about 10 words. At the end of the time, he was assessed and he could spell every word correctly. The teacher thought he felt that a bit of magic had happened.

Hugo is so proud and pleased with his progress that he wanted his own name used in this story.

Avoid more problems when learning new skills p 8 p 8 p 11 p 9

Any time a dyslexic/ SpLD person is learning new skills, the skills are vulnerable to being learnt with embedded dyslexic/ SpLD problems – not a desirable state of affairs. This exercise is a way of reflecting on your experience of learning new skills and thinking about the best way for you to learn new skills.

Exercise: Avoid more problems when learning new skills

- What were the skills you learnt most recently?

- How did you learn them?

- What task was involved?

- How important are the skills to you?

- What made them easy to learn?

- What was hard about learning them?

- How easily have you been able to adapt the skills to other uses?

Reflection question: Is it a good idea to try out something new on tasks that are really important to you?

- It is OK if you can easily make changes to the way you do something later.

- It is not OK if you find the first way you tackle something leaves a strong impression.

- If this is your experience, try out new systems or skills on tasks that you don’t mind about too much but that you are quite interested in.

- It is not OK if you are likely to think: “Can I trust this new approach? Will it muck up this task or topic?” Doubt like this will not allow you to explore the new approach freely.

- If in any doubt, use a task or topic that doesn’t matter too much first; struggling with dyslexic/ SpLD tangles is such a pain, it’s worth avoiding new problems.

- You won’t give a new skill or system a fair trial, if you are worried about it or the task.

Use interesting, but unimportant topics for new techniques p 316

Key point: Use interesting but unimportant topics for new techniques

I usually suggest that students try new ideas on something that isn’t essential to them, but is interesting. If they are trying a new technique and worrying about getting everything, they will not give the new way a fair trial.

Use recall, not re-read p 159

Key point: Use recall, not re-reading

Re-reading information does not strengthen memories in long-term memory.

Systematic recall does strengthen memory.

Recall and check p 62

You want to be sure that the thinking preferences you have identified are right for you. This exercise is a good one for doing just that. It is also a good exercise to use when you are learning something; it helps you identify what you are learning well and what is missing.

Exercise: Recall and check

One test to see how well you have uncovered your Thinking Preferences is:

- to find something you don’t care about but which is similar to material you would like to remember (not always a possible option) [once familiar with the technique, use it on material you do care about].

- understand it and organise it in a way that seems to fit the topic

- convert the important parts into notes; use any method of making notes that suits you; it is quite good to leave about 10 minutes between the end of working on the topic and making the notes

- the next day, see how much you can remember and why; check against the notes you made

- think about the links between ideas or items that you remember and

- try to work out any relationships between them

- work out their relationship to you

- look at the ideas or objects that you didn’t remember

- see what you could adapt from the things you did remember

- see whether you are bored or have some other adverse reaction

- alter the way you think about these things so that they are hooked into your memory more firmly

- keep assessing what you are learning about your way of thinking through this mechanism.

Lack of flexibility p 61

Key point: Lack of flexibility

For most dyslexic/ SpLD people, there is little flexibility in the way they learn:

- they have to do it the way that works for them

- they need to be disciplined to keep to that way

- trying someone else’s way often leads to no learning

- the determination to learn in their own way can be misinterpreted as bloody-mindedness.

Teaching

Introduction

Teaching is partly about the way your students receive your methods of teaching and your expectations of how they might learn. This selection relates to the dynamics between teacher and student, including some processes that hinder your students from learning from your teaching.

CloseThe starting point matters p 88

Key point: The starting point matters

You need to work with the most pressing task that your student is facing. If you decide you will work on a skill or topic unrelated to his task, he is unlikely to be able to learn. Even if he tries to pay attention, the task will be lurking in his mind and preventing the right neurons from firing together, see Where to Start for several suggestions.

Mental on/off switch p 86

Key point: Mental on/off switch

It is important to recognise that students are not wilfully switched off from learning; and to recognise that their brains and minds need switching on in a different way in order for learning to happen.

Geography by 3 methods p 178

Story: Geography by 3 methods

One geography teacher said in a workshop, “By the time I’ve taught a topic in 3 different ways, almost all the children have got it.”

Planning p 200

Key point: Planning

- [Good planning can assist learning knowledge and skills, and using them.]

- Planning can be undertaken before your student has all the necessary knowledge or skills; the planning allows her to be clear about any work still to be done.

- Knowing what she wants to achieve (i.e. Know the Goal of Any Task) before she does any research can make the research processes much more effective.

- Knowing what she wants to achieve can also help her to be clear about any skills she needs to acquire.

Mistakes contribute to learning p 159

Key point: Mistakes contribute to learning

A positive attitude towards mistakes can also be an important part of dealing with any difficulties. If a mistake is viewed as an opportunity to find out more about the way a child is learning or approaching tasks, it can be seen as beneficial.

Mistakes can be viewed as evidence to assist learning rather than failures which sap the self‑confidence of the learner.

Unobtrusive objective observation of a pupil p 167

Tip: Unobtrusive Objective Observation of a pupil

Use games and tasks to observe a pupil objectively. Choose ones that aren’t part of basic learning about words and numbers. You need to avoid any mistakes being built into a Learned Confusion at the early stages of important skills.

- Give a pupil tasks to do; observe how he responds.

- Get a pupil to teach you something he knows very well, or a topic that he is interested in.

- Get him to give you instructions about a game he can play.

- Get him to describe something he knows well: his room, his way to school, his computer desktop.

Analyse the way he tells you or shows you the task, or game. Use Thinking Preferences in the analysis.

Rote learning doesn't work p 118, 216

Insight: Rote learning not working

For people who learn by understanding, rote learning doesn’t work.

Absence of subliminal learning p 57

Key point: Absence of subliminal learning

Generally, subliminal learning should not be taken for granted for dyslexic/ SpLD learners. They need to pay attention in very specific ways to everything they need to learn and they need to use their individual thinking preferences.

Correct spelling but no spelling learnt p 175

Story: Correct words but no spelling learnt

One girl was given a page of spellings to practise by writing each word out 3 times. She handed in the finished page and it was accepted as correct.

What the teacher didn’t know was that her method was to write all the first letters down the page, then all the second, and third and so on going down the page each time until the words were finished. Writing the complete words was too boring.