Case study: UGC, social media and the BBC

This case study outlines how BBC News has developed since 2005 in terms of responding to ‘User Generated Content and Social Media’. Initially a response to the stories and images sent in to the BBC, the corporation’s policy has moved towards full engagement with a variety of social media networks.

The Case Study is offered as an extended example of work covered in The Media Student’s Book, 5th Edition, especially Chapter 8 ‘New media’ in a ‘new world’? and Chapter 12 News and its futures.

Case Study written by Claire Wardle, BBC College of Journalism.

In the days that followed the 2004 Tsunami, the BBC was inundated with messages from people in the area who had been directly affected, as well as footage of the event taken on mobile phones and video cameras. Managing the amount of information sent to the BBC was a major undertaking for the news organisation and it was clear that developments in mobile technology meant this type of material would feature heavily in news reporting from this point forward.

So in January 2005 a 3 month pilot project was funded by the BBC to support the creation of a User Generated Content (UGC) Hub in order to capture the best material sent in by the ‘audience’ and to disseminate it back out across the organisation.

Just as the pilot was being evaluated, the London bombings occurred in July 2005, demonstrating that UGC was now an invaluable way of reporting breaking news stories. Within 6 hours they had received 1000 still images, 4,000 text messages, and 20,000 emails. The main news bulletins included camera phone footage taken by survivors as they walked through the underground tunnels and the first image of the bus which had been taken in Tavistock Square by a passer-by. As a result the Hub was made a permanent feature of BBC newsgathering operations and it has grown significantly since the pilot. It is now a 24 hour operation with 23 members of staff.

- Every day journalists on the Hub are responsible for a number of tasks:

- monitoring the picture console which collates the images people send to yourpics@bbc.co.uk;

- overseeing the SMS interface which shows the text messages received in response to BBC news output;

- inserting ‘post-forms’ at the bottom of BBC online stories asking people to get in touch if they have particular expertise or who are located near a breaking news event.

The journalists also oversee the online ‘Have Your Say’ discussions, making sure contributors do not break BBC House Rules. They also use the message boards for newsgathering purposes, looking for people talking about particular experiences, and in those cases contacting the contributor to see if they would be willing to talk in more detail to a journalist covering the story. It quickly became clear that the UGC Hub was an invaluable resource on everyday stories as well as breaking news events.

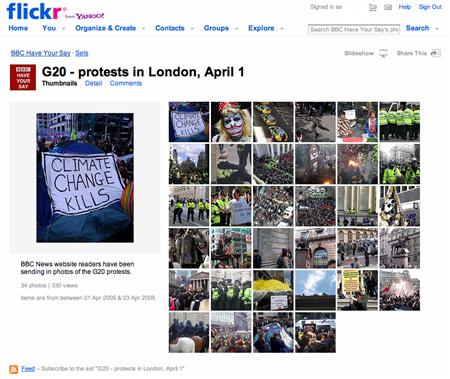

These tasks are still part of the remit of the UGC Hub. But significant shifts in web technology and audience behaviour means the Hub is no longer a passive recipient of content sent in by contributors. With the explosion in the popularity of sites such as Facebook, Twitter and YouTube, people are much more likely to share photos, videos or comments with their ‘friends’ on these sites, than send material to the BBC. It also means that during a breaking news story, journalists can go to these sites to find out who is nearby and is talking about their experiences, and contact them directly. As a result, members of the UGC team now spend their time on these social networking sites listening to online conversations, engaging with members on the different sites and looking to reflect these conversations and experiences in BBC output.

Journalism and ethics

The fact that journalists are using social networking sites to find useful material might sit uneasily with some, because of the ethical, privacy, and copyright issues which surround the use of material from these sites. But internal training and guidelines exist to ensure BBC journalists understand the subtleties of these issues. Overall however there is a recognition that even though the BBC receives over 10,000 emails per day and 1,000 still pictures per week, research showed that those who did submit content to news organisations in Britain were more likely to be educated, and from higher socio-economic groups, and the numbers who contributed were less than 5% of the total estimated audience. If the BBC is looking for a particular case study to illustrate a news story, then using Facebook to find someone who has been directly affected gives access to a much broader range of people.

Journalists on the Hub have developed an expertise in terms of verifying sources, aware that hoaxes are an ever present threat. During the Iran election protests in June 2009, they were able to highlight the fact that the Picture Agencies were sending material around to news organisations which had been downloaded from YouTube. Despite being labelled as footage from the current events, the images were in fact of protests from previous demonstrations. Similarly, during the Fort Hood shootings, journalists at the Hub used Twitter to contact someone who appeared to have uploaded a photo of the injured gunman from the hospital.

@BBC_HaveYourSay: @MissTearah Hello, it’s James at BBC News in London. I saw your picture from Fort Hood. It would be great to talk to you today. Are u free?

Her reply confirmed that the photo was not authentic and the BBC UGC journalist replied:

@BBC_HaveYourSay: @MissTearah Thanks for letting us know. We thought the email was suspicious. I’m glad we did not publish your pic. I’m sorry to trouble you.

Social Media is changing the way organisations like the BBC are engaging with audiences. Previously audiences received their news by watching the major news bulletins, or turning to the BBC homepage in the morning. For growing numbers of people, their social networking sites have become their main portal, and the online space where they spend most of their time. As a result they will only engage with BBC content if it is shared with them via their network. This means that the BBC and others have to be in these spaces, sharing, engaging and providing good content there, with the hope that this will bring audiences back to the BBC; audiences who have maybe got out of the habit, or don’t feel there is anything of interest to them there. Many BBC programmes, news and non-news now have Facebook fanpages, Flickr groups, YouTube videos, and Twitter accounts. By engaging in these spaces, the BBC hopes it is more likely to find the best content to include in its output. But it also hopes other people will find this content via these social networks and will come back and spend time with BBC output as a result.