Chapter 17 - Managing boundaries

Download All Figures and TablesNote Click the tabs to toggle content

Helping the coachee to not depend on you

The coach has a role as a source of motivation. Coachees may undertake a flurry of activity in the week or so before a session, to ensure that they don’t have to admit that they haven’t acted on the self-commitments they have made in the previous session. This motivational dependency can be very gratifying, but it is also dangerous. How will the coachee self-motivate once the coaching relationship ends?

The coach has a responsibility to keep an eye out for such dependency and to address it. For many executives, a primary reason for having a coach is to remind them of what they need to do but are unlikely to get around to without an external stimulus. So it’s sometimes important to engage in an exploration of how the coachee can increase their self-motivation or create a network of motivational support. Some useful questions here include:

- Who else is a stakeholder in this issue?

- How can you involve them in reminding you of what you need to do?

- What do you allow to interfere with achieving your goal?

- In what ways are you rewarding yourself for not taking the actions you have committed to? How could you change the way you reward yourself to achieve a different/better outcome?

- What stories do you tell to yourself to avoid taking full responsibility for your actions on this issue? Could you replace these with a different story, which would increase your self-motivation?

- What happens just before you backslide? What could you change about your behaviour/ thinking pattern to achieve a different, better outcome?

Managing the coachee who needs more support than the coach can give

People going through a temporary crisis typically need support. How much support they need depends on a number of factors, including how severe the crisis is, how many simultaneous crises there are for this person, and the extent to which their coping mechanisms are being overwhelmed. The coach must be alert to the possibility that the coachee needs professional help (for example, counselling) and ready to help them accept the need for such help.

It is relatively common for the coach to be faced with a situation where they appear to be the only person the coachee can lean upon. The dangers here are many. They include:

- The potential to overwhelm the coach.

- The potential to build an unhealthy dependency.

- The likelihood that the relationship purpose may be undermined by concentration on immediate, emotional needs rather than longer-term developmental needs.

- An expectation on the part of the coachee that the coach will solve some or all of their problems, rather than that they must solve them themselves.

The coach can be of greatest real assistance by:

- Re-contracting to clarify the boundaries of the relationship – what they can and can’t provide.

- Helping the coachee separate out and clarify what the issues are.

- Helping the coachee identify what sources of support they can call upon, outside the coaching relationship.

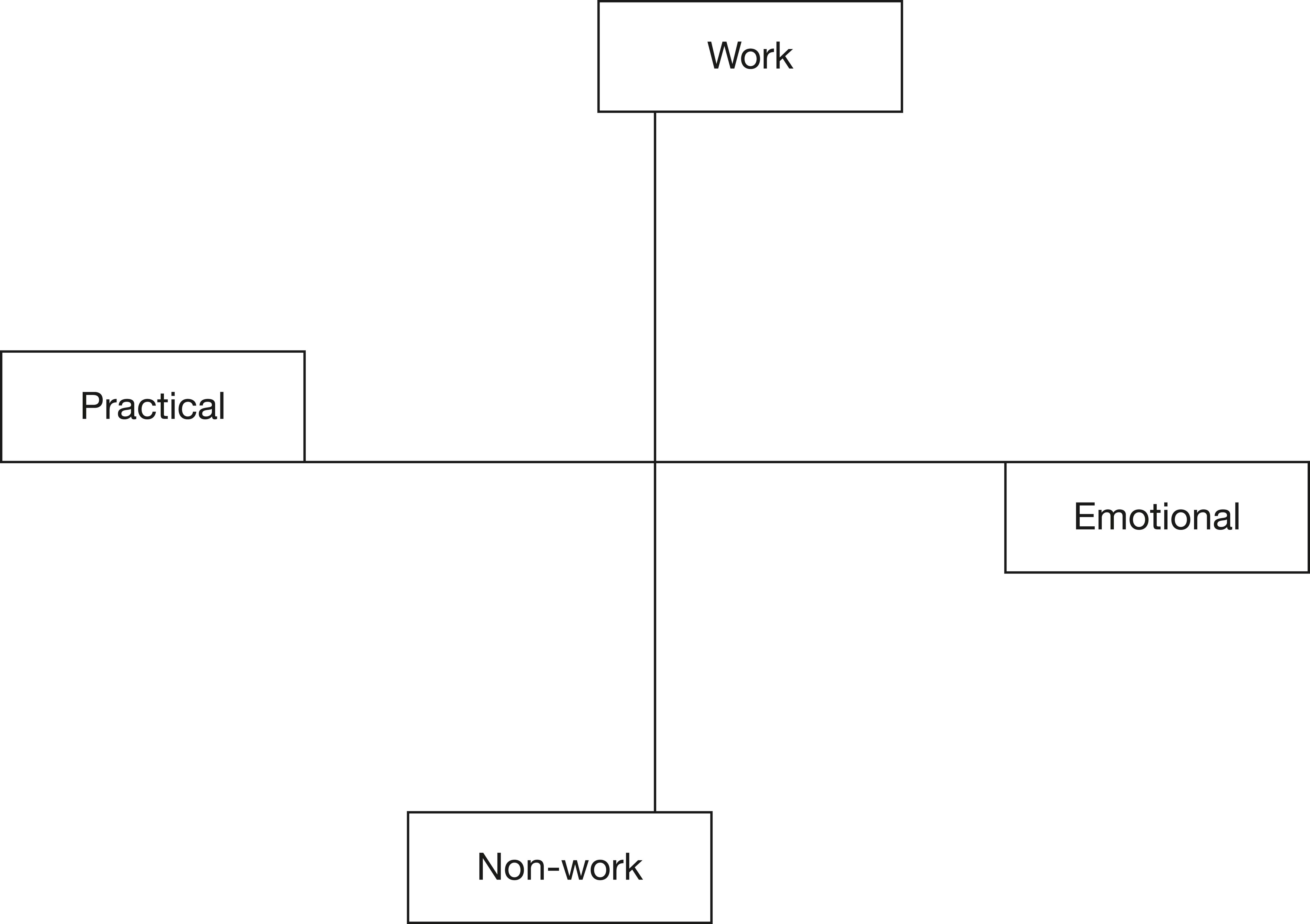

A useful tool for achieving this is the support matrix as shown in Figure 17.1.

Download Figure

The matrix provides a basis for describing who can help in each quadrant; and where the gaps are. Useful follow-on questions include:

- Who might be more helpful, if they were more aware of your circumstances/feelings?

- Who would you like to be more helpful?

- Who might be able to recommend additional sources of help you are not aware of?

- Who do you know who has been in a similar position to your own? What lessons could you learn from their experience?

In terms of how the coachee leans on the coach, useful questions include:

- What are the three (maximum) most helpful things I can do in my role as coach/mentor to help you?

- What specific part should this learning relationship play in supporting you?

- How much of this situation would you like to be able to solve with your own resources? How can I help you make that happen?

Maintaining the boundaries

It’s important for the coach or mentor to recognise when the coachee may need professional therapeutic help to deal with particular emotions or mixes of emotions. A rule of thumb here is to consider counselling if:

- The emotion is at the extreme of one of the cascades, or flips between two extremes, and

- The emotion is a permanent or semi-permanent feature of the coachee’s predominant mood.

If in doubt, discuss with a qualified colleague, preferably in the context of supervision of practice.

Referring on

Knowing when to refer a coachee on can be a difficult decision. The simplest guideline is that you should consider referring on when you are aware that the issues under discussion or the depth of the discussion are outside of your competence, or require a re-contracting of the relationship.

The process of referring on should involve:

- Explaining to the coachee why you feel that you have a boundary issue.

- Exploring their feelings and preferences about the order issues should be tackled in (e.g. should you leave discussing a career decision until they have dealt with a bereavement issue, which may be clouding their judgement?).

- Exploring, if appropriate, the benefits and disadvantages of referring on or working on the issues within the current relationship.

- Advising on who to refer on to (should you offer a choice?) – this may require you to take advice in turn from a coaching/mentoring supervisor or from the HR department.

- Ensuring that the handover is managed efficiently and empathetically. (The professional you refer on to will need to have some basic information about why you felt this was appropriate, but may not require your thoughts on a diagnosis, if you have made any.)

- Ensuring there is an efficient process for liaising between the professional therapist (or other specialist) and the coach/mentor, either while the two relationships continue in parallel, or when the coachee is ‘handed back’.

If you decide to continue in the relationship, at the same time as referring on, it is important to re-contract with the coachee and to form a clear contract with the therapist. The decision whether to re-contract should depend on:

- How confident you feel in your ability to work in the new area (and what evidence/relevant experience you have to justify that confidence).

- Whether the issue can be isolated from the initial or overarching purpose of the relationship; or whether it replaces that purpose.

- Whether it will be in the coachee’s best interests to deal with these issues together or separately.

Contracting with the therapist should cover at a minimum:

- What understandings and communication should there be between the therapist and myself? (In particular, what are the boundaries of confidentiality in this circumstance?)

- What conversations do we need to have to ensure that the boundaries are maintained?

- What process will we have to ensure that we can raise concerns with each other?

Any situation where the coach considers referring on is a potential issue to discuss with a supervisor.

Managing disclosure

Personal disclosure is an important part of an open, trusting relationship. It allows us to build multiple points of connection, in terms of shared experiences, shared values and shared hopes and fears. Overused, it can have the opposite effect -- as anyone will testify, if they find themselves on a train or plane sitting next to someone determined to tell you their life history in the first few minutes of acquaintance!

Effective disclosure is 100 per cent coachee-focused – in other words, it is about providing information that will help build trust and encourage openness in the other person. You have to trust in order to be really trusted. So a basic ground rule of disclosure is first to ask yourself: ‘How will saying this add value to this conversation?’

There are three types of disclosure:

- Empathetic disclosure aims to demonstrate shared experience, either real (‘I've been there, too’) or projected (‘I can imagine how frustrating that must be’).

- Manipulative disclosure is about achieving superiority over the other person -- for example, ‘It was so much worse for me!’

- Emotional disclosure involves revealing feelings within you, which the other person may not be aware of. It is fundamental to gestalt therapy.

It is important in coaching to avoid manipulative disclosure entirely, and to use empathetic and emotional disclosure sparingly and deftly. A little goes a long way! With empathetic disclosure, it's often enough to indicate that you understand and have similar experiences, but not to go into any detail. If the coachee wants to tap into your experience, they will indicate this.

Emotional disclosure can be used in a number of ways, all based upon what you are feeling in the moment. For example:

- ‘I can feel a shift in how you are approaching the relationship with this person’.

- ‘When you spoke about this last time, your enthusiasm was infectious. Now I'm feeling almost bored. What has changed for you?’

- ‘I'm sensing that you are reluctant to address this issue...’

- ‘I'm feeling that you have a real sense of purpose now’. (This is also empathetic disclosure.)

- ‘I'm wondering about the irritation I'm feeling as you talk about the conversation with your boss... Could that be what she was feeling, too?’

Emotional disclosure can be highly supportive -- or highly challenging. It requires quite a lot of courage sometimes, but used wisely, it usually has the effect of deepening both the conversation and the coaching relationship.

Who can I work with?

Every coach has boundaries in respect of who they can work with. Some of these boundaries relate to the difference in our experience or culture – it is generally easier to build empathy and rapport with someone with whom we share important life experiences. So, for example, convicted prisoners often find it helpful to be coached or mentored by someone who has themselves been in jail, but has subsequently ‘gone straight’.

Equally, some boundaries are needed because the coach is too similar or too drawn to the coachee. When a relationship demands a high level of personal disclosure, the level of intimacy may need careful management, if the coach is not to over-identify with the coachee, for example.

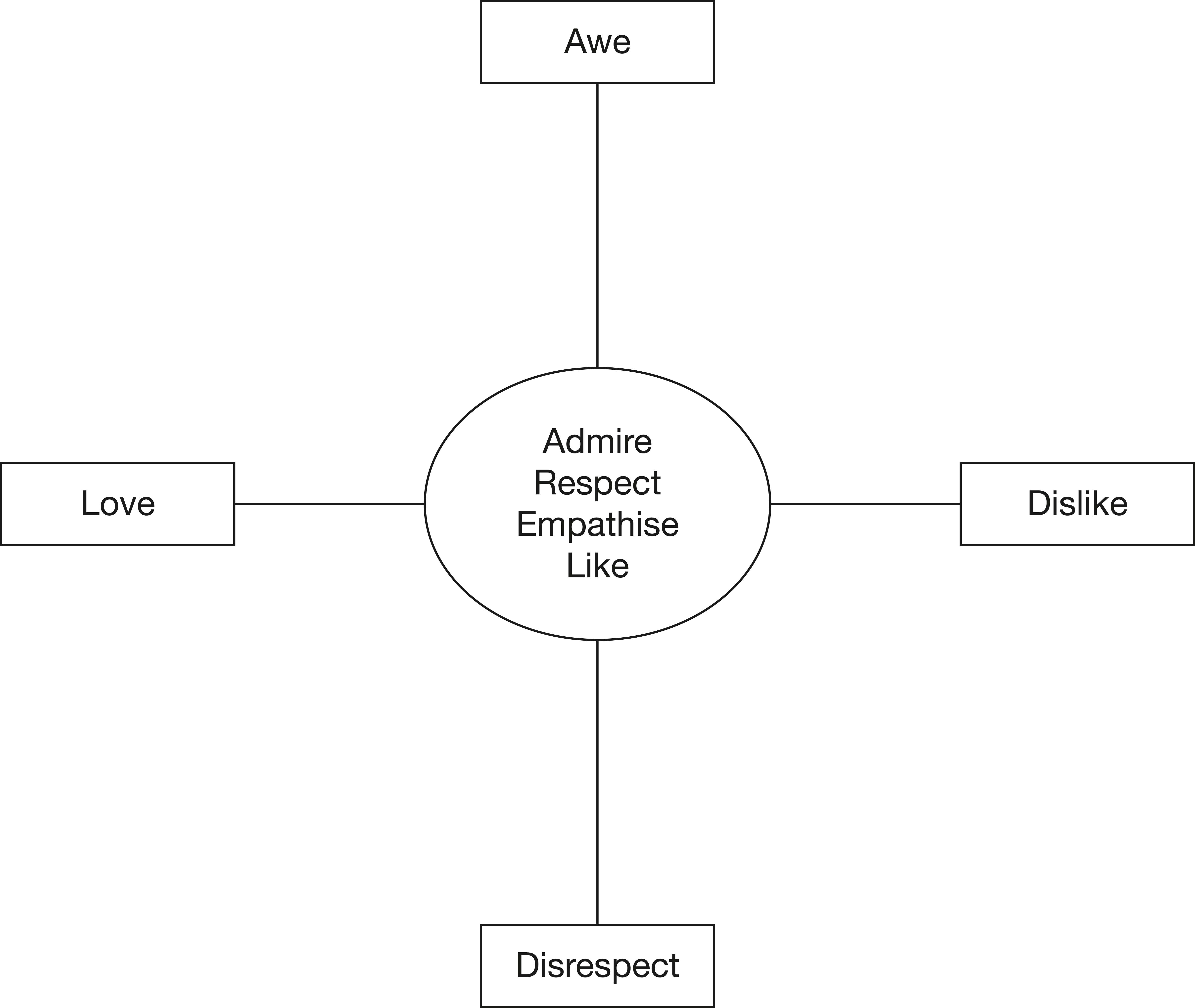

Figure 17.2 illustrates some aspects of the boundary dilemma. The place where the coach can operate most effectively and most comfortably is in the middle, where three elements of an effective helping relationship defined by Carl Rogers (Rogers, 1961) come together. These are:

- Genuineness (congruence).

- Respect (unconditional positive regard).

- Empathy.

Too much respect (awe) does not lead to a healthy relationship. Nor does too little respect (disrespect). Similarly, it is difficult (though not impossible) to coach someone you don’t like. And liking them too much can blind you to characteristics or behaviours which they would benefit from addressing in the learning conversation.

Download Figure

The opportunity for the coach or mentor is to experiment with these boundaries and with specific coachees to see how far they can expand their central circle. They can, for example, learn to accept and work with people who they might otherwise avoid as coachees because they disliked them, by searching out and finding things they can like about them. The coach can similarly learn to change their own responses to authority and power, to enlarge their comfort zone with respect to people who currently overawe them.

Recognising and challenging boundaries is an important part of continuous development for a coach. One of the authors tested his own boundaries by taking on an assignment in the justice system, which meant that he would have opportunities for dialogue with a variety of prisoners. He moved most of his boundaries in this context well beyond their previous point, but found a new boundary when it came to prisoners who had abducted and murdered children. At this point, it became difficult for him to apply any of the Rogerian principles. While this is an extreme example, we do take the view that most people – coaches and mentors included – tend to seek coachees who are like themselves. We commend the developmental opportunities inherent in seeking coachees who are different.

A systems approach to manage the balance between coaching and psychotherapy

Any coach or mentor who has been through an advanced level of training in the role, should be fully aware of the dangers of accepting presented issues at face value. One experienced executive coach recently said that it was a rarity for any of his coachees’ presented issues to be what they really needed to work on. Almost invariably, the presented issue was a clue to deeper or broader issues, which the coachee had not identified or had been deliberately or unconsciously avoiding.

At the same time, however, it is important that the coach should not place himself or herself in the role of amateur psychologist. Having enough knowledge to recognise indicators of psychological conditions that require specialist help is critical in recognising and respecting the boundaries of competence. But stepping over those boundaries is both dangerous (for both parties) and irresponsible.

Does that mean that all professional coaches and mentors should be psychotherapists? It is difficult to sustain such a position, especially with regard to mentoring, where critical parts of the relationship are empathy and mutual respect, based on the mentor’s practical experience in the world the mentee wants to learn about. In a sounding board role, clinical detachment is a hindrance to the learning dialogue.

So how can the non-therapist coach or mentor ensure that they manage this delicate balance, adding real value to the coachee’s thinking, assisting them in making behavioural change, yet remaining within the bounds of their psychological competence? The answer appears to lie in the development of an entirely different competence – systems thinking.

Systems thinking is about taking a holistic approach that views the individual and his or her environment as interconnected and complex. Instead of focusing on problem/solution, it attempts first to understand the context in which an issue is grounded. It explores the impact or influence parts of this larger picture have upon each other – what may make a change in one factor more or less effective, and what unexpected outcomes may occur. (See Chapter 13 for techniques using systems thinking.)