Chapter Resources

This chapter looks at the difference between memory, whether individual or collective, and the more disciplined approach towards the past that characterizes an awareness of history. All groups have a sense of the past, but they tend to use it to reinforce their own beliefs and sense of identity. Like human memory, collective or social memory can be faulty, distorted by factors such as a sense of tradition or nostalgia, or else a belief in progress through time. Modern professional historians take their cue from nineteenth-century historicism, which taught that the past should be studied on its own terms, ‘as it actually was’. However, this more detached approach to the past can put historians in conflict with people who feel their cherished versions of the past are under threat.

- How does historicism differ from other ways of approaching history?

- What are the key features of historical awareness?

- What is social memory and how can it distort the past?

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of periodization?

- What are the problems with a narrative of history as progress or as regress?

- Are history and social memory always in conflict?

Myths of popular history

When the Germans invaded France in May 1940 the British Expeditionary Force was forced to retreat to the port of Dunkerque (Dunkirk), from where it had to be evacuated under heavy fire. Many in Britain mistakenly perceived the operation as a success, and the ‘Dunkirk spirit’ came to denote cheery optimism and resolution in the face of overwhelming odds.

On Easter Tuesday 1282 the people of Palermo rose up against the French, massacring as many as they could find while they were at vespers (evening prayer). The ‘Sicilian Vespers’ became a symbol of the immense potential power of a popular uprising to strike without warning and to oust a foreign occupying force, and therefore had resonance far beyond its immediate historical context. The Mafia also has its origins in medieval Sicily, where it was one of a number of clandestine brotherhoods operating a pseudo-feudal system outside the law. Mafia ‘barons’ ruled their neighbourhoods, often combining benevolence with ruthless enforcement of their authority. Elements of the Mafia were caught up in large-scale Italian emigration to the United States in the late nineteenth century, where they moved into protection rackets and organized crime. The Italian–American Mafia rose to public prominence through its involvement in supplying illegal alcohol during the years of Prohibition (1919–33), becoming part of American mythology in the process.

In 1776 representatives of the thirteen British colonies in North America, including John Adams, Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin, met in Philadelphia and signed the Declaration of Independence, renouncing British rule and founding the United States. Nowadays they are popularly revered and romanticized in America as the ‘Founding Fathers’. It remains rare – indeed, it is considered almost unpatriotic – for Americans to subject the Founding Fathers to serious critical historical evaluation.

Malcolm X (1925–65), a leading figure in the radical black civil rights movement in the United States in the 1960s, called for a major reappraisal of the mythology of American history and of the role Africans played in it.

Periods of history

It is easy to forget that historical periods are later constructs; no one at the time knew they were living in ‘the ancient world’ or ‘the Middle Ages’. These terms also reflect the values and judgements of those who coined them. The term ‘Middle Ages’ was coined by scholars of the fifteenth and sixteenth-century Renaissance to refer to what they saw as a long period of ignorance and superstition which interposed between the ‘golden age’ of the ancients and their own day. Periods are often defined in terms of centuries or decades – ‘the eighteenth century’, ‘the Sixties’ – or else in terms of rulers, as in ‘Tudor England’ or ‘the Victorians’, though this can be unsatisfactory: ‘Victorian’ attitudes can be traced up to the First World War; the reign of the first Tudor monarch, Henry VII, was not significantly different from that of his Yorkist predecessors; and the features most commonly associated with the youth culture of the Sixties can be more accurately dated from c.1965 to c.1975. Historians often deliberately ignore conventional periodization: Frank O’Gorman has written of the ‘long eighteenth century’, from the ‘Glorious’ Revolution of 1688 to the Reform Act of 1832, while Eric Hobsbawm has written of a ‘short twentieth century’, beginning with the First World War and ending with the fall of European communism in 1989–91.

Enlightenment and the Romantics

The Enlightenment of the eighteenth century grew out of the scientific revolution of the previous century, which had stressed the importance of learning through observation and deduction rather than by the unquestioning acceptance of past authority. Enlightenment thinkers such as Montesquieu and Rousseau applied these ideas to human society, teaching that humans’ ‘natural’ condition is to be free, and that human behaviour should be governed by reason rather than by irrational and ‘unnatural’ tradition or religious faith. Enlightenment philosophy was an important influence on the leaders of the French Revolution. Romanticism was a cultural and intellectual movement in the early nineteenth century, heavily influenced by the ideas of the French Revolution. It sought to give free range to the emotions, and thereby to attain eternal truths. The Romantics found inspiration in the romances and tales of the Middle Ages, for example the tales of King Arthur. Nationalism, also originating in the French Revolution, emphasized the importance of a sense of collective national identity. Much of nationalism is concerned with preserving and cherishing ‘traditional’ national language and culture, but it is also closely identified with the idea of the nation-state, in which states are organized along national ethnic lines.

An illustration from Walter Scott's novel, Waverley (1814), a romantic portrayal of the Scottish Highlands.

- ‘Molly house’ sub-culture

- http://cabinetmagazine.org/issues/8/bailey.php

- An interview with one of the first historians to study the ‘molly house’ sub-culture of the gay community in London in the eighteenth century.

- Malcolm X

- http://www.malcolmx.com/about/bio.html

- During the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, Malcolm X called for African-Americans to rediscover their history.

- History Workshop

- http://www.historyworkshop.org.uk/

- The History Workshop and its journal were begun in the 1960s and 70s by several left-wing historians to promote the idea of ‘history from below.’

- Battle of Kosovo (1389)

- http://www.balkanhistory.com/kosovo_1389.htm

- The Serbs’ defeat at the Battle of Kosovo in 1389 at the hands of the Turks is commemorated every year and remains an important source of national identity.

- Daniel Boone

- http://www.history.com/topics/daniel-boone

- Daniel Boone (1724-1820), an American frontiersman, remains a popular folk hero in the American imagination for his role in exploring and settling Kentucky.

- Julius Nyerere’s Ujamaa

- http://www.nathanielturner.com/ujamaanyerere.htm

- Julius Nyerere, the first president of an independent Tanzania (previously Tanganyika), sought to govern the nation on the principles of ujamaa, or brotherhood. In this speech, Nyerere laid out how he believed these principles led to socialism.

This chapter looks at some of the different ways in which historians have tried to explain the purpose of their work. Some see history as a study in itself which needs no wider justification; others see it in terms of the inexorable march across time of great forces, human or even divine, which explain both how we got to where we are and where we might be heading; others deny that history has any lessons for us at all. Historians explain the past in response to present-day concerns and questions. History can certainly allow us to experience situations and face alternatives that we would not otherwise encounter, and in that sense it serves a useful purpose; it can also reveal that aspects of modern life are not as old, or as new, as we have assumed. But how can we learn any useful lessons from history – especially for the future – when so much depends on the details of the historical context? And if history does not repeat itself, what sort of a guide can it provide for the present?

- Why have some people subscribed to a form of metahistory? Why have others rejected history altogether?

- What are the practical applications of studying history?

- Can history be a guide for how to act in the present? What are the benefits and drawbacks of using history in this way?

- How can history challenge concepts that seem ‘natural’?

- Should historians seek to make their work relevant or should history be studied only for its own sake?

Marxism and the English Revolution

Marxism, the philosophy of Karl Marx (1818–83), was one of the most influential political and intellectual movements of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Marx held that all human history can be explained in terms of dialectic, the conflict between different social classes for control of the main means of economic production. This produces a succession of stages from feudalism to capitalism, and from capitalism to a communist society, in which workers enjoy the benefits of their own labour. The English Civil Wars (1642–9) were for many years understood essentially as a conflict for authority between king and Parliament. Marxist historians working in the twentieth century, notably Christopher Hill (1912–2003), saw it in much more radical terms, as an attempt to create a new society on principles of equality and individual liberty. In this sense it constitutes an English Revolution in the same way as the later revolutions in France and Russia, as a shift from aristocratic to bourgeois and even working-class hegemony.

Renaissance

The Renaissance was a fifteenth-century European cultural and intellectual movement which began in Italy and eventually spread to France, Germany, the Netherlands and England. It drew inspiration from new discoveries in the art and writings of the ancient Greeks and Romans. Artists experimented with perspective and depth, while sculptors created remarkably lifelike reproductions of human and animal forms. Renaissance writers explored Greek philosophy and sought to marry its ideas with those of Christianity.

Transformation: by peace and by war

In 1948 the white Afrikaaner government of South Africa imposed a policy of strict racial segregation known as apartheid. Black African resistance came to centre on the imprisoned African National Congress leader, Nelson Mandela. By the 1980s South Africa seemed close to civil war, but concessions by the government of F.W. de Klerk, and especially the release of Nelson Mandela in 1990, enabled the country to undergo a remarkable peaceful transition to democracy. In 1994 Nelson Mandela became the first black President of South Africa.

Nineteenth-century Germany presents a contrasting example. Germany consisted of a large number of separate states. German nationalists wanted to amalgamate them into a single, unified German empire, but Austria, the largest and most powerful German state, presented a problem, partly because it had a large non-German empire of its own, and partly because it had long dominated Germany and was unlikely to welcome the creation of a large, independent German state. In the event, in 1871 Germany was united into a single empire under the leadership of the militaristic north German kingdom of Prussia; Austria and its empire were excluded.

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa

- http://www.justice.gov.za/trc/

- Facing up to history can sometimes be a form of national therapy. This philosophy underlay the creation of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in post-apartheid South Africa.

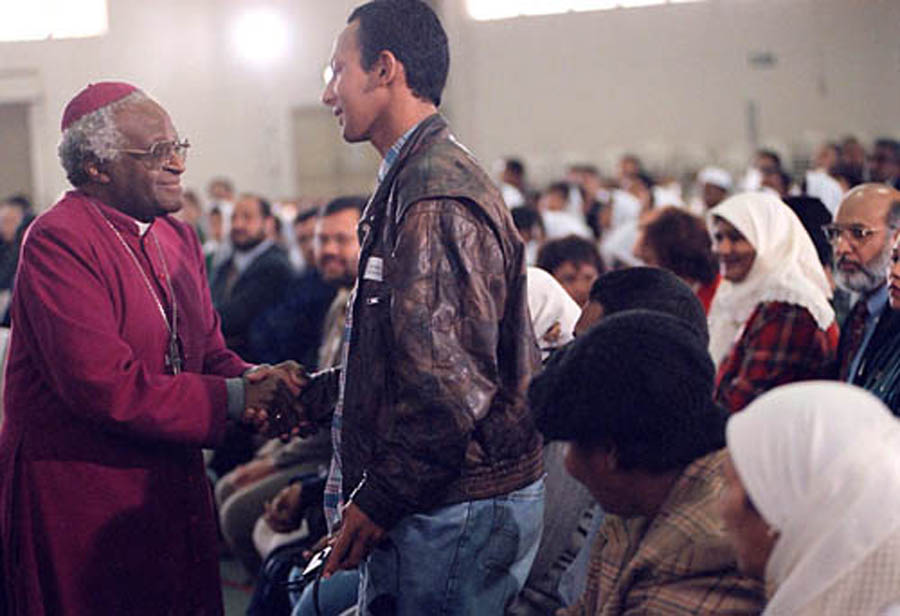

South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission provided a forum where those who had committed crimes in the name of apartheid could admit openly what they had done and receive forgiveness from their victims. This process of facing up to a painful recent past proved helpful in allowing South Africans to work together to face the future. © Topfoto/Image Works.

- Gulf War (1990-1)

- http://www.history.com/topics/persian-gulf-war

- The Gulf War of 1990-1 demonstrated that the media and the general public rarely consider present events in their wider context.

U.S. Marine artillerymen set up their 155 mm howitzer for a fire mission against Iraqi positions on 20 January 1991 during Operation Desert Storm.

- African National Congress

- http://www.anc.org.za/show.php?id=206

- The formation of the African National Congress in 1912 was part of a wider historical trend of anti-imperialist movements opposing foreign rule.

- Matrimonial Causes Act of 1857

- http://spartacus-educational.com/Wmatrimonial.htm

- This important act was part of a wider trend toward the liberalization of divorce laws throughout Europe.

- Race

- http://discovermagazine.com/1994/nov/racewithoutcolor444

- History can challenge concepts that seem ‘natural’ but really aren’t. ‘Race’ is one clear example: while the idea that humanity can be classified into ‘races’ has been widely held in previous centuries, this belief is actually without foundation.

- Gender roles in Victorian Britain

- http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/trail/victorian_britain/

- The Victorian ideal that a woman’s place was in the home came under fire by the turn of the nineteenth century.

Mapping the field

Much of the history students encounter is concerned with political events, but that is far from the limit of the historian’s interest or concerns. Historians have greatly widened the range of their studies since the heyday of Victorian constitutional history. Today, no aspect of human thought and activity is excluded from the scope of historical study. Economy, society, mentality and culture all have their place in the curriculum. This chapter describes and classifies this richness.

- Why has political history enjoyed such a prominent position within the discipline? Why did this begin to change in the twentieth century?

- What are the merits of a biographical approach to history? What are the limits to such an approach?

- What is ‘social history’ and what explains its increasing prominence?

- How does the author explain the ‘material/mental’ dichotomy? Are the two necessarily at odds?

- What subjects might be appropriate to study from a global perspective? And from a local perspective?

Hegelian dialectic

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831) was the leading German philosopher of the early nineteenth century. He argued that human events in history were determined by the operation of dialectic – the clash of opposing forces or ideas out of which emerged a synthesis, which would in its turn be challenged by an opposing antithesis. Hegel believed that this process would lead eventually to a state of harmony based upon Christian ethics and morality. Karl Marx, who was much influenced by Hegel, ‘turned him on his head’ by divorcing Hegel’s ideas from their Christian framework and applying the dialectic model to the clash of class interests throughout history, leading ultimately to the control of economy and society by the working class.

Tudor inflation

Across sixteenth-century Europe there developed a steady and alarming rise in prices which caused considerable hardship. The reasons for the inflation were not clear to contemporaries, who blamed anything from human greed to the enclosure of common land to graze sheep. The English government of Edward VI responded by debasing the coinage in order to put more money into circulation, but this simply led people to put their prices up still higher. Historians long thought the inflation was caused by the influx of gold and silver bullion from the Americas, but nowadays it is thought to be a result of the huge rise in population during the period.

- Paris Peace Conference

- http://www.firstworldwar.com/source/parispeaceconf_wilson.htm

- The Paris Peace Conference of 1919 decided the fate of post-war Europe and is therefore fodder for political and diplomatic historians.

- History of Parliament Online

- http://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/

- Sir Lewis Namier’s prosopographical method for studying politics has continued and biographies of over 20,000 Members of Parliament are now available online.

- History of Trade Unionism

- https://archive.org/details/historyoftradeun00webbuoft

- Sidney and Beatrice Webb’s History of Trade Unionism (1894, revised edition 1920) was an early work that examined social and economic history.

- Eminent Victorians

- http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/2447

- Lytton Strachey’s Eminent Victorians (1918) poked fun at the genre of historical biography.

- Poverty during the Elizabethan Era

- http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/tudors/poverty_01.shtml

- As the population of Britain grew during the sixteenth century, economic difficulties left many in poverty.

- Salvation Army

- http://www.salvationarmy.org/ihq/history

- The Salvation Army, a Christian charitable organisation modelled on an army, was formed in Victorian Britain.

- Big History

- https://www.bighistoryproject.com/chapters/4#intro

- The Big History Project is an ambitious attempt to trace history on a universal scale. Aside from non-traditional historical questions like the development of the universe, they also consider big questions like the growth of agriculture in human societies.

- ‘The Return of Martin Guerre’

- http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0084589/

- From her work as a historical consultant on the 1982 film, ‘The Return of Martin Guerre’, Natalie Zemon Davis wrote a book of the same name, which became a classic of microhistory.

The raw materials

Students rarely work with historical sources in their original state. Examination papers and textbooks contain short, labelled extracts, which bear little resemblance to the originals. What sort of sources are available to the historian? How did they come to be made available, and how might this affect their usefulness? This chapter gives a fuller idea of the provenance of, and problems with, the sort of sources historians habitually use.

- Why has the written word been so important to historians? What other kinds of sources are available?

- Explain the division between primary and secondary sources, and the problems with such a clear division.

- Is there a hierarchy of primary sources? Are some more valuable than others?

- How have governments and other institutions sought to preserve their records? What are the challenges for accessing these materials?

- Are there any drawbacks to the increasing digitisation of primary materials?

The main reading room of the Thomas Jefferson Building. Built between 1890 and 1897, it is the oldest of the three Library of Congress buildings.

Roman historians

Roman history poses a problem for the historian because we are so heavily dependent on the accounts of Roman historians about whose sources we know very little. Julius Caesar (100–44 BCE) wrote detailed accounts of his campaigns in Gaul and against his political rival Pompey which are generally regarded as valuable but heavily one-sided. Cornelius Tacitus (AD 55–120) seems to have used his access to senatorial records to write his histories of the early years of the empire. Tacitus took a gloomy view of the growth of imperial power, but without access to his own sources we have no yardstick against which to check his version of events. Gaius Suetonius (AD 69–140) wrote a series of short sketches of the first twelve Roman Emperors which became the model for biographical writing, but his habit of recording accurate detail alongside gossip and hearsay, without any attempt to distinguish between the two, makes him a particularly problematic source.

Satire as a source

Satire is a potent but difficult source for historians. It dates very quickly and is often full of allusions and references to people and events that have sunk into obscurity. Its reliance on irony, in which writers say the opposite of what they mean, can mislead the unwary student. It is also easy to fall into the trap of assuming wrongly that the satirists’ views were universally held. There was a thriving market in eighteenth-century England for satirical journals, like The Tatler and The Spectator. Jonathan Swift’s famous Gulliver’s Travels was originally a scathing satire on Whig politics and society, though it has survived as a fantasy tale for children in a way Swift could never have anticipated.

‘Namierism’

Sir Lewis Namier (1888–1960) was a historian of eighteenth-century politics who developed a new approach to political history through exhaustive documentary study. His 1929 work The Structure of Politics at the Accession of George III was based upon the accumulation of biographical details of every single MP and member of the House of Lords in 1760. This comprehensive approach to the study of institutions is properly known as prosopography. He adopted a similarly exhaustive approach to his study of the Duke of Newcastle (Prime Minister 1754–6 and 1757–62), whom he once said he felt he knew better than he knew his own wife. Namier’s work led to the setting up of the multi-volume History of Parliament, which contains detailed studies of individual MPs and constituencies.

- Great Zimbabwe

- http://www.bbc.co.uk/worldservice/africa/features/storyofafrica/10chapter1.shtml

- The impressive ruins at Great Zimbabwe, built during the eleventh and fourteenth centuries, unfortunately held no written source material.

- Works by Julius Caesar

- http://www.forumromanum.org/literature/caesarx.html

- Julius Caesar’s (100 BCE – 44 BCE) commentaries on his military campaigns in Europe and North Africa, written during or soon after the campaigns, intended to inform the Roman people about the wars but also to favourably shape his image.

- Works by Tacitus

- http://www.forumromanum.org/literature/tacitusx.html

- Roman historian Tacitus’s (c. 56 CE – c. 120 CE) best known works are Historiae (Histories), which chronicled Roman political history from 69 CE – 96 CE, and Annales ab excess divi Augusti (Annals), which covered the years 14 CE – 68 CE, both of which were based on official Roman government documents.

- Works by Suetonius

- http://www.forumromanum.org/literature/suetoniusx.html

- Roman historian Suetonius’s (c. 69 CE – c. 135 CE) most important work was De vita Caesarum (The Twelve Caesars), which provides biographies of twelve successive Roman leaders, from Julius Caesar (100 BCE – 44 BCE) to Domitian (51 CE – 96 CE).

- Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

- http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/657

- The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (this edition is a nineteenth-century translation) compiled the history of the Anglo-Saxons. It was begun during the reign of Alfred the Great (849 – 899) and was still being updated as late as the twelfth century.

- Matthew Paris’s Chronica Majora

- Volume 1

- https://archive.org/details/matthewparisseng01pari#page/

- Volume 2

- https://archive.org/details/matthewparisseng02pari#page/

- Volume 3

- https://archive.org/details/matthewparisseng03pari#page/

- Jean Froissart’s Chronicles

- http://www.maisonstclaire.org/resources/chronicles/froissart/froissartschronicle.html

- Jean (John) Froissart (c. 1337 – c. 1405), a mediaeval French historian, wrote a number of non-fiction and fiction works. His most important historical account was the Chronicles (this site provides an incomplete version of the nineteenth-century translation), describing the Hundred Years’ War between England and France.

- Gerald of Wales

- http://www.gutenberg.org/browse/authors/c#a536

- Gerald of Wales (or Giraldus Cambrensis in Latin) (c. 1146 – c. 1223) was an archdeacon and historian. His most important historical works, The Description of Wales and The Itinerary of Archbishop Baldwin through Wales, document the history of his native Wales.

- Samuel Pepys diary

- http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Diary_of_Samuel_Pepys

- Samuel Pepys (23 February 1633 – 26 May 1703) was an English naval administrator and Member of Parliament. He is most well-known because of the diary he kept from 1660 to 1669, providing an insight into his public and private life and a personal view of major events of his time.

- John Evelyn diary

- http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/41218

- http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/42081

- John Evelyn (31 October 1620 – 27 February 1706) was an English gentleman whose famous diary documented his life from 1640 until 1706. Like Pepys’s diary, Evelyn’s diary provides an important look at his private life with commentary on contemporary events.

- Chancery

- http://www.medievalgenealogy.org.uk/guide/rol.shtml

- The Chancery rolls, records of dispatches in the king’s name, are a key source for mediaeval English history.

- State Papers

- http://gale.cengage.co.uk/state-papers-online-15091714.aspx

- The State Papers offer insight into royal government beginning with the reign of Henry VIII.

- American Memory

- http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/index.html

- The American Memory project at the Library of Congress aims to put written and other sources (sound, images, maps, etc.) online for free and open access.

- National Archives Online Collection

- http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/records/our-online-records.htm

- The National Archives in London have begun to digitise their collection. Thus far, over 5% has been digitised, including census and military records.

- British Newspaper Archive

- http://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/

- The British Newspaper Archive intends to digitise the newspaper collection of the British Library over the next ten years. This is a searchable database of their scanned collections so far.

- Old Bailey records

- http://www.oldbaileyonline.org/

- The Old Bailey was London’s criminal court from 1674 to 1913. Their records are now online and fully searchable.

- Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England

- http://www.pase.ac.uk/index.html

- This project aims to provide information about all the recorded inhabitants of Anglo-Saxon England from the sixth century to the eleventh.

- British Census Online

- www.1901censusonline.com

- www.1911census.co.uk

- The 1901 and 1911 censuses are fully available online.

- Hansard

- http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/

- Hansard is the report of debates in the British House of Commons and House of Lords. The site contains records from 1803 to 2005.

Primary Sources

Firsthand accounts for Roman History

Sources for Mediaeval Europe

Benedictine Monk Matthew Paris’s (c. 1200 – 1259) Chronica Majora (this edition is a nineteenth-century translation) is a history of the world, beginning with the creation of the world as described in the Bible, and ending with Paris’s death in 1259.

Diaries

Other sources

Using the sources

Having tracked the source material down, how should the historian set about using it? This chapter looks at different approaches that historians adopt: some start out with a specific set of questions, some follow whatever line of enquiry the sources themselves throw up. The chapter draws a distinction between the source critic, who analyses source material in great detail, and the historian, who does this too but puts the sources in the context of a wider knowledge of the period to which they relate. Sources have to be analysed for forgery, the author’s bias has to be detected and taken account of, and historians need to know how to spot when material has been removed from the record or covered up. Digitized material is not exempt from these procedures. The archive itself – traditionally regarded as authoritative – is increasingly scrutinized for ideological distortion.

- Discuss the different strategies involved with the source-oriented method versus the problem-oriented one?

- How can historians verify a document’s authenticity?

- What does it mean for a source to be reliable? What factors can historians take into account to assess a source’s reliability?

- What is ‘unwitting evidence’ and why is it important?

- How should historians use statistics?

- Why must historians be critical of both digital records and those held in archives?

Bishop Stubbs’ Select Charters and the British constitution

The work of the nineteenth-century British historian Bishop William Stubbs (1829–1901) is an example of the application of scholarly historical research to contemporary concerns. Stubbs was Regius Professor of Modern History at Oxford, and later Bishop of Chester and of Oxford. His compilation of medieval charters and his three-volume Constitutional History of England were drawn up to show through exhaustive documentary evidence the antiquity – and therefore the legitimacy – of English legal and political institutions. His work is therefore as important nowadays for what it reveals about the Victorian mentality as it is for understanding the period Stubbs was actually studying.

British rule in Palestine

Palestine, roughly equivalent to modern-day Israel and Jordan, was a province of the Turkish Ottoman Empire until after the First World War, when the British took the area over, under mandate from the League of Nations. However, the British were also bound by their undertaking under the 1917 Balfour Declaration to establish a homeland in Palestine for the Jewish people. Palestinian resistance to Jewish immigration grew steadily through the 1930s. After the Second World War and the Holocaust, increasing demands for large-scale Jewish settlement in Palestine enjoyed considerable international support. Jewish terrorist groups, Irgun and the Stern Gang, launched a series of bomb attacks on British troops and administration buildings. British attempts to create some sort of bi-national Arab–Jewish state failed, and in 1947 the United Nations (UN) agreed to partition Palestine between Jews and Arabs. Britain handed the mandate back to the UN in 1948, and the UN immediately declared the Jewish state of Israel.

Palaeography

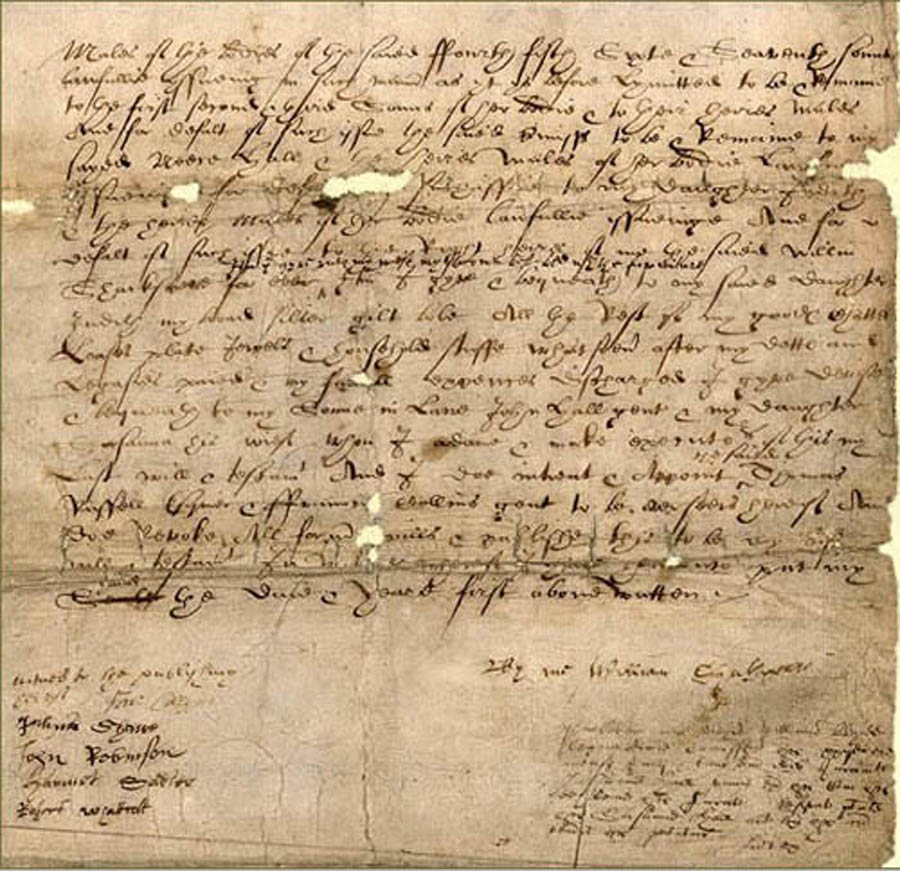

Palaeography is an important skill for historians who intend to study handwritten documents that are centuries old. This is necessary because, not only has a particular language itself evolved over time, the ways of writing various characters of the alphabet have also evolved, meaning the characters may be written differently from the ones today. Additionally, writing produced by scribes or secretaries might be filled with abbreviations and other forms of shorthand which can be difficult for the untrained eye to decipher. The writing of an individual scribe might even have its own distinct style. Palaeography can also be used as a way to determine the approximate date and location a document was produced, or to authenticate documents or expose forgeries, as in the case of William Henry Ireland (1777-1835), whose forgeries of William Shakespeare’s plays were discovered partly through analysis of the handwriting. Many universities offer courses in palaeography, particularly for those studying Mediaeval or Early Modern Europe.

Historians may need to be trained in palaeography if they intend to study centuries-old handwritten documents, as in this case, the 1616 will of William Shakespeare.

- Hitler Diaries

- http://hoaxes.org/archive/permalink/the_hitler_diaries/

- An in-depth article on the Hitler Diaries, one of the most famous recent examples of forged historical documents.

- http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/features/3636377/

- A retrospective article by the deputy-editor of The Sunday Times on publishing the Hitler Diaries.

- The Second Reform Act (1867) and the Balfour Declaration (1917)

- http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/1867_reform_act.htm

- http://history1900s.about.com/cs/holocaust/p/balfourdeclare.htm

- The Second Reform Act and the Balfour Declaration are both important historical documents, but must be read in context as parts of historical processes.

- Destruction of British colonial documents

- http://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2013/nov/29/revealed-bonfire-papers-empire

- As the British Empire was being dismantled, colonial officials often destroyed important documents to cover up British actions.

- Domesday Book

- http://www.domesdaymap.co.uk/

- http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/domesday/

- The Domesday Book was the record of a massive land survey covering England and Wales, completed in 1086 on King William the Conqueror’s orders.

- Donation of Constantine

- http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Donation_of_Constantine

- The Donation of Constantine, purportedly written by the Roman Emperor Constantine in 315 – 317, was one of the most famous forgeries in history. In the document, used to bolster Papal authority in the mediaeval period, Constantine supposedly gave control of Rome and the western part of the Roman Empire to the Pope. The document was uncovered as a forgery by a Catholic priest, Lorenzo Valla (c. 1407 – 1457), in 1439 – 1440.

- The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire

- http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/1681

- Written by English historian Edward Gibbon, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire was a landmark history work. Gibbon relied heavily on primary documents to recount the history of the Roman Empire from its height to the aftermath of its fall. The work was published in six volumes from 1776 to 1789.

- The Story of the Ashantee Campaign

- https://archive.org/details/cu31924090934690

- Written by Winwood Reade, this work detailed the British campaign against the state of Asante in West Africa in 1874, often making the Asante seem particularly brutal through lurid and exaggerated descriptions of human sacrifice.

- British Census reports

- http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/records/census-records.htm

- Much of the data of British census reports from 1841 is now searchable online, although some websites may charge to view the full records.

Primary Sources

Writing and interpretation

Most students’ experience of historical writing is limited to producing essays or assignments, or addressing questions and problems set by others for assessment purposes. Historians, however, are usually able to set their own questions of the material they have unearthed, and can plan and design their work as they choose. How, then, does the historian turn research into historical writing? And what role does the historian’s interpretation play in the process?

- What are the various forms of historical writing? How can they best be balanced?

- How has the writing of history changed since the nineteenth century?

- Contrast the writing of a narrow, focused history with a large-scale synthesis.

- What are the rewards and challenges of writing comparative history?

- What skills or qualities does a historian need to possess?

- Why do historians disagree so much?

Alexis de Tocqueville (1805–59)

Alexis de Tocqueville was a French lawyer, historian and social commentator. His 1835 study of Democracy in America argued that although Americans enjoyed greater liberty than Europeans, their liberty led to oppression of the poor by the materialistic rich on a much greater scale than was to be found in the monarchies of Europe. De Tocqueville was a staunch libertarian and opponent of the centralizing tendencies of bureaucratic government; he was Foreign Minister in the short-lived second French Republic (1849– 52) but refused to serve under the autocratic government of Louis Napoleon (Emperor Napoleon III from 1852). His classic study of The Old Regime and the French Revolution argued that the Revolution and the Napoleonic Empire that followed it merely continued the oppressive, centralizing tendencies of the Bourbon regime. He also taught that an oppressive regime is at its most vulnerable precisely at the moment when it begins to reform itself.

Origins of the First World War

The causes of the First World War (1914–18) have long proved a fruitful source of historical controversy. The wartime allies concluded that Germany was directly to blame and drew up the draconian Treaty of Versailles on that basis; German resentment at this helps to explain popular support for Hitler. By the 1960s most historians were more prepared to explain the outbreak of the war in terms of the complex interplay of political, diplomatic, military, social and personal factors. However, the German historian Professor Fritz Fischer broke this consensus by arguing that German diplomatic correspondence showed that the German government had indeed been planning for war and was largely to blame for it. The British historian A.J.P. Taylor argued provocatively that in the end the crucial factor was that each state’s railway timetables were so rigid that it was impossible for even the most powerful government, once orders had been given for troops to move, not to invade its neighbours. Few modern historians share Taylor’s extreme view, but the Fischer thesis still retains a substantial body of support.

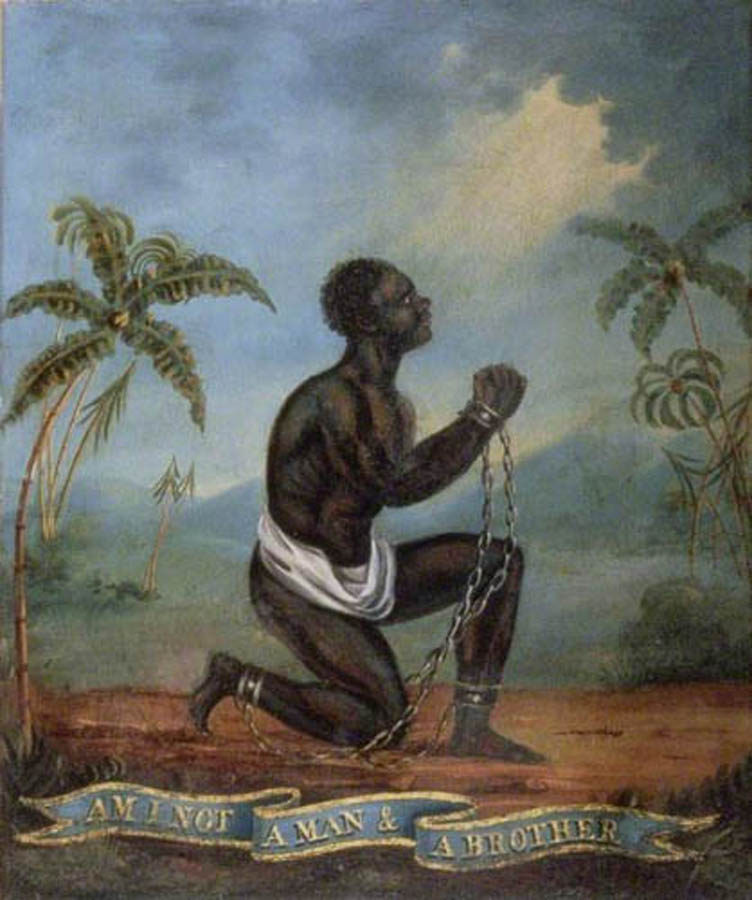

The abolition of slavery

The campaign against the transatlantic slave trade began among evangelical Christians in late eighteenth-century England and pioneered many of the features of modern pressure groups. The movement’s most important convert was William Wilberforce, Tory MP for Hull and a close friend of the Prime Minister, William Pitt the Younger. Despite support from Pitt and the Opposition leader, Charles James Fox, it took until 1807 to persuade Parliament to outlaw the slave trade, and till 1833 to abolish slavery itself. Illiterate and without skills, thrown into a job market in which they could earn only the lowest wages, many former slaves were reduced to penury.

'Am I Not A Man And A Brother?' was a famous slogan used by British abolitionists to evoke empathy for slaves, but changing economic conditions may have been just as important as these humanitarian campaigns in ending slavery.

- Puritans

- http://www.history.com/topics/puritanism

- The rise of Puritanism in England (and subsequently in the United States) was one of the consequences of the English Revolution.

- The Cambridge Modern History

- http://www.uni-mannheim.de/mateo/camenaref/cmh/cmh.html

- Planned by Lord Acton, the Cambridge Modern History (1902-1912) was a collaborative effort to cover the grand sweep of European history since the mid-fifteenth century.

- Samuel Johnson

- http://www.historytoday.com/peter-martin/our-debt-dr-johnson

- Aside from Samuel Johnson’s pithy put-down of historians, he remains one of the most quotable figures in British history.

The limits of historical knowledge

Historians make many claims for their subject, but can any historical account amount to anything more than its author’s personal take on the past? This chapter looks at the debate surrounding the essential nature of historical work and therefore, to some extent, its value. The positivist position sees history as a form of science, in which historians amass facts from hard evidence and draw valid conclusions; the idealists on the other hand stress that the incomplete and imperfect nature of the historical record obliges the historian to employ a considerable degree of human intuition and imagination. Challenging both positions are the Postmodernists, who point to the highly subjective values and assumptions latent not just in the historical record but in the very language that historians use to express their ideas. Does this mean that objective historical accounts are an impossibility, and if so, what is the student to make of a philosophy that questions history’s very existence as a subject?

- Should history be considered a science?

- What is a historical fact? How should historians select facts?

- Why has the positivist view of history fallen out of favour?

- Why is present-mindedness inevitable among historians? Is this always a bad thing?

- How has postmodernism challenged the positivist view of history?

- Has postmodernism dealt a fatal blow to the study of history? How can historians respond to its challenge?

Inductive reasoning

Historians have to achieve a balance between deductive and inductive reasoning. Deductive reasoning is employed when the conclusion is entirely supported by the information on which it is based, known as the premise. Thus, if the premises are a) that all cats are vertebrates and b) that Toby is a cat, we can safely deduce that Toby is a vertebrate; indeed no other deduction is possible. Deductive reasoning is well illustrated in the methods adopted by the fictional detective Sherlock Holmes, who once remarked that, when all other possibilities have been eliminated, what is left, however unlikely, must be the solution. The point of the italics is that many people allow their expectations, drawn from everyday experience, to influence their interpretation of data. This is inductive reasoning. For example, a visitor to London who saw a host of red buses and black taxis might, understandably but still wrongly, conclude that all London buses are red and all London taxis are black. Mathematicians rely entirely on deductive reasoning and can be impatient of scientists’ tendency to slip into the inductive; for historians, with their often patchy and incomplete evidence, the temptation to rely too much on purely inductive reasoning is even stronger. Every time a historian generalizes from a single incident or example he or she is employing inductive reasoning, which further evidence might well show to be mistaken.

Holocaust denial

In the closing stages of the Second World War, allied armies overran German concentration camps and uncovered evidence of the Nazis’ policy of exterminating Jews, Gypsies and other groups. However, a move also got under way fuelled by extreme right-wing and anti-semitic groups in different countries to deny that the Holocaust had ever happened. A characteristic approach of Holocaust denial is to adopt an outwardly respectable, academic manner and to appear to subject the evidence for the Holocaust to careful and objective scrutiny. For example, it is often pointed out that no document has survived with Hitler’s signature on it ordering the murder of Jews. From this it is argued, implausibly, that Hitler can have known nothing of the Holocaust. Holocaust denial is based upon the systematic suppression or distortion of the evidence. (For the court case involving David Irving, see Chapter 2.)

Whig history

The Whigs were a political group that dominated British politics in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Whiggery developed out of the parliamentary side in the English Civil War and retained a strong attachment to the rights and privileges of Parliament, whose virtues, the Whigs believed, could be explained by a particular reading of English history. The Whigs interpreted it as a long battle with the Crown for the restoration of the ancient rights of Parliament, which they fondly believed had been enjoyed in Anglo-Saxon times but lost at the time of the Norman Conquest. Historians have long since shown the Whig version of events to be myth, but the general theme of progress towards a pinnacle in the present day remained very popular. Herbert Butterfield attacked Whig history for looking at medieval or Tudor institutions in entirely modern terms and not taking the contemporary context into account; left-wing historians have rejected Whig history for its over-confident, patriotic tone. The general Whig tendency, however, to see modern conditions or attitudes as the peak of perfection and then to look to the past to see how we attained it, is by no means confined to constitutional history and can be found in such diverse fields as women’s history or the history of science and medicine.

- Auguste Comte

- http://www.victorianweb.org/philosophy/comte.html

- Auguste Comte (1798-1857) developed the philosophy of positivism in the nineteenth century. This philosophy would influence many scientists, as well as some historians.

- Karl Popper

- http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/popper/

- Karl Popper (1902-1994) was a philosopher of science who argued that all scientists can do is to refute hypotheses, never actually prove them. This outlook has also been taken up by some historians.

- Ferdinand de Saussure

- http://www.learn.columbia.edu/saussure/

- Ferdinand de Saussure (1857-1913) was an influential linguist whose ideas helped to open the way for the postmodernist approach to texts.

History and social theory

What role should theory play in the work of a historian? Some approach history from a Marxist point of view and find that the application of social theory helps to make sense of a past that might otherwise defy analysis. However, others see such theorizing as dangerous, twisting the facts to fit the theory. This chapter considers the relationship between history and different social theories. It suggests that Marxism in particular might have rather more to offer the historian than its detractors have allowed for.

- Why do many histories use theories? Why do some reject their use?

- Why must historians be cautious when using techniques of social science?

- Contrast the popular understanding of Marxist theory with the reality.

- To what extent is Marxism deterministic?

- Why has Marxist theory proved such a useful tool for historians?

- With the fall of the Soviet Union, has Marxist theory continued to be relevant for historians?

Theorists and the ‘English Civil War’

Marxist history has made a particularly important contribution to the historiography of the English Civil Wars of 1642–9. In his book The World Turned Upside Down, the British historian Christopher Hill broke with orthodox analysis, which had concentrated on the constitutional arguments between Parliament and the Crown, to look at the explosion of radical political and religious groups the period also witnessed, such as the Levellers and Gerrard Winstanley’s Diggers. Hill was not merely putting forward a version of ‘history from below’; he was presenting the period as one in which constitutional and religious arguments were essentially conduits for a more fundamental conflict between classes. Other historians have responded to the relentlessly secular terms of Marxist analysis by stressing the roots of the conflict in actual religious belief, rather than viewing religion as a vehicle for non-religious issues of class control. The growth of nationalist movements in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland has led to a separate reappraisal of the period in British terms, in which the conflict between Crown and Parliament is seen as part of a much broader interplay of religious and constitutional issues in Ireland and Scotland, as well as England. Where the period used to be referred to simply as ‘the English Civil War’, it is now common to hear reference made, according to the standpoint of the speaker, to ‘the English Revolution’ or ‘the British Civil Wars’.

E.P. Thompson and The Making of the English Working Class

E.P. Thompson’s 1963 The Making of the English Working Class won a wide popular readership for the way it brought the experiences of ordinary people to the historical forefront. It was the first systematic attempt to provide the working class as a whole, as opposed to the trade unions or the co-operative movement, with a heritage and a sense of collective identity. Thompson’s book remains popular, particularly among those on the political Left, though it is admired across the political divide for the clarity of its style and for the humanity of its judgements. Thompson himself went on to become a leading figure in the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament.

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels (1820–95) was the son of a prosperous German cotton manufacturer. He acted as his father’s agent in Manchester, then the centre of European cotton manufacture, and was thus able to gain a detailed understanding of the workings of the British economy and to observe at close hand the lives of the working classes, which he described in his 1844 exposé, The Condition of the Working Classes in England. He met Marx the same year, and the two men produced The Communist Manifesto in 1848, laying out the basic theory of communism and calling on working men of all lands to unite to free themselves from oppression. After the failure of the European revolutions of 1848–9, Marx joined Engels in England and began the mammoth task of research in the British Museum Reading Room, which was to result in 1867 in his detailed critique of the capitalist system Das Kapital: Kritik der Politischen Ökonomie (Capital: Critique of Political Economy). Marx took a leading role in the First International, an international workers’ association which, he hoped, would precipitate proletarian revolution and establish the communist order, but he was unable to prevent it from splitting into Marxist and anarchist factions. Marx died in poverty in 1883 and was buried in Highgate Cemetery in London, where his tomb is still a place of pilgrimage for socialists and communists. Engels devoted the rest of his life to translating and editing Marx’s works in order to bring them to a wider readership.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989, popular insurrection overturned communist governments across Eastern Europe. Some held that Marxism itself had been discredited; graffiti on this statue of Marx and Engels in Dresden, in East Germany, has them declaring ‘we are not guilty’, a view shared by many who saw the Soviet dictatorship as a perversion of Marxism. Not everyone agreed, however, and many statues of Marx and Engels, like those of Lenin, were overturned and smashed. © Alamy/ICP.

- Cliometrics

- http://eh.net/encyclopedia/cliometrics/

- Cliometrics was the application of economic models to history developed in the 1960s and 1970s. While the method promised to explain history through laws, the approach has proved controversial.

- Communist Party Historians’ Group

- http://newhistories.group.shef.ac.uk/wordpress/wordpress/history-from-below/

- The Communist Party Historians’ Group comprised many influential Marxist historians. This article argues that their work had a dramatic impact on shifting historiography to focus on ‘history from below.’

Cultural evidence and the cultural turn

Whereas the social theories discussed in the previous chapter focus on structure, change and agency, cultural theory attends to meaning and representation. Its influence is evident today in the very high profile enjoyed by cultural history. To some extent cultural history draws on the well-established field of art history (and also the history of film). But its approach to questions of meaning is much more strongly influenced by literary theory and by anthropology. The chapter ends with an assessment of the present state of history in the light of what has come to be called the cultural turn.

- How have historians understood the different meaning of ‘culture’? What was the ‘cultural turn’?

- What can be gained by studying visual sources like art and film?

- How have historians attempted to bring psychology into the study of history? What objections have been made to this approach?

- What insights have come from historians’ use of literary theory?

- Why have techniques from cultural anthropology found a ready audience among historians? What are the limits of these techniques?

Freud and psychoanalysis

The Austrian neurologist Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) developed the process of psychoanalysis, whereby patients were first relaxed and then encouraged to speak freely about their feelings and memories, often going far back to childhood. His 1900 work The Interpretation of Dreams argued that dreams bring out mental pain and trauma that is otherwise repressed in the mind. There was fierce controversy over his tracing of the development of sexual feelings and desires to early childhood, including the Oedipus complex, named after the figure in Greek mythology who unknowingly kills his father and marries his own mother, by which a young boy experiences a powerful desire to possess his mother and a fear that his father might retaliate by castrating him.

Freud held that the mind is divided into three parts: the id, which represents inherited, innate instinct; the ego, which represents the individual’s sense of his or her own self within the world; and the super-ego, which reflects those wider social values and ideals that have been learned from parents or through schooling or experience. The Swiss psychiatrist Carl Gustav Jung identified different types of personality, notably the introvert and the extrovert, and formulated the theory of the ‘collective subconscious’, those hidden attitudes and fears that are shared by the members of a particular cultural grouping.

Freud’s theories proved a major inspiration to artists and writers and were particularly popular in the United States, whereby the late twentieth century psychoanalysis had become a virtual industry. Although the basis for Freud’s theories has come under increasing attack in recent years, public interest in psychology and the working of the mind remains as strong as ever.

Development of photography

Photography developed in the early nineteenth century, although the two principles of photography, the understanding of the camera obscura (a chamber which projects light from the outside onto a screen inside) and the knowledge that certain materials become altered when exposed to light, had been known for millennia. The first person to combine the two was Thomas Wedgwood (1771-1805), who used white paper treated with silver nitrate to capture an image, but Wedgwood was unable to retain the image before it turned completely dark. Nicéphore Niépce (1765-1833) conducted his own experiments and produced the oldest surviving photograph (View from the Window at Le Gras) in 1826 or 1827 by using bitumen, a kind of petroleum tar. Niépce began work with Louis Daguerre (1787-1851) and together they refined the technique, but Niépce’s death in 1833 left Daguerre to carry on the experiments. Daguerre returned to using silver compounds and was also able to reduce the necessary exposure time to produce an image from several hours to just a few minutes. In 1838 Daguerre produced the first photograph of a person, unwittingly captured as Daguerre photographed a Paris street. Henry Fox Talbot (1800-1877) had been doing his own independent experiments in Britain and revealed his work soon after Daguerre released his photographs in 1839. Talbot’s technique differed from Daguerre’s in that it produced a negative copy of the image, which could be used to produce multiple positive copies. As photography boomed in the nineteenth century, newer developments included film to replace metallic plates and colour photography, all of which led some to proclaim the death of painting. This prediction obviously did not come true, but photography did force artists to dramatically rethink the purpose of art.

- Nazi propaganda

- http://www.bytwerk.com/gpa/posters1.htm

- http://www.bytwerk.com/gpa/posters2.htm

- http://www.bytwerk.com/gpa/posters3.htm

- Historians have viewed the Nazis’ use of propaganda before and during their reign in Germany as an important factor in their rise to power and their ability to retain control of the population. The collection here includes posters from before and after the Nazis’ rise to power in 1933.

- Soviet propaganda

- http://www.visualnews.com/2011/08/29/soviet-propaganda-posters-of-the-second-world-war/

- The Soviet Union also used propaganda to a powerful effect; in this case, to build support for the war against Nazi Germany.

- Political Cartoons

- http://www.cartoons.ac.uk/group/history-british-political-cartooning

- A selection of political cartoons from the British Cartoon Archive at the University of Kent.

- http://www.loc.gov/teachers/classroommaterials/primarysourcesets/political-cartoons/

- A selection of political cartoons from the Library of Congress.

- Bayeux Tapestry

- http://www.aemma.org/onlineResources/bayeux/bayeuxIntro.html

- The Bayeux Tapestry (which is not actually a tapestry, but an embroidered cloth) was created in the 1070s to celebrate the Norman Conquest of England by William the Conqueror (c. 1028 – 1087). The document is nearly 70 metres long and contains about 50 scenes with accompanying Latin text.

- Renaissance Art

- http://www.history.com/topics/renaissance-art

- Renaissance art has been an important area of study for art historians.

- 19th century photography

- http://www.vam.ac.uk/page/0-9/19th-century-photography/

- Modern photography developed in the nineteenth century. The Victoria and Albert Museum in London has a collection of nineteenth-century photographs.

- Films of everyday life in 1901-1907

- http://player.bfi.org.uk/collection/edwardian-britain-on-film/g1dzZrZDoQMz1ZIcurTtZSmrKYCj9Psj

- These films from the Edwardian Era in Britain were discovered at Blackburn in 1994 by the Mitchell and Kenyon film company.

- Documentaries during New Deal Era

- http://www.parelorentzcenter.org/works/

- This website contains links to films made by Pare Lorentz (1905 – 1992), one of the leading documentary filmmakers during the New Deal Era in the United States. Lorentz’s films captured the devastation of the Great Depression and both natural and man-made environmental degradation.

- Freud’s essay, “Leonardo Da Vinci, a Memory of His Childhood”

- http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/34300

- Sigmund Freud’s (1856 – 1939) essay, “Leonardo Da Vinci, a Memory of His Childhood,” published in 1910, was one of the earliest works of psychohistory. The essay offered an interpretation of the famous Italian thinker’s childhood through a psychoanalysis of his painting.

Gender history and postcolonial history

This chapter examines some of the most dramatic extensions of history’s subject matter. Fifty years ago women were ignored, and Third World countries were treated in a narrowly Western perspective. Today, women’s and gender history is regarded as central to the understanding of the past. Meanwhile postcolonial historians are not only developing histories of Africa and Asia ‘from below’, but are insisting that the history of the former colonial powers be reassessed from the perspective of the colonized.

- How has women’s history evolved since its inception in the 1970s?

- How does gender history differ from women’s history?

- How has the cultural turn impacted the study of the history of gender?

- What is the goal of postcolonial history?

- How has postcolonial history developed since the 1960s?

- Why have practitioners of postcolonial history expressed ambivalence about their discipline?

- How are gender history and postcolonial history similar?

The history of the family

This is one of the areas where the history of gender has made a decisive contribution. For many people ‘family history’ means the recovery of their own genealogy and personal details about their ancestors. Historians, on the other hand, are chiefly interested in the family as a building block of society. The earliest studies were demographic; they drew heavily on the census records, focusing on family size, migration and relations with kin (see, for example, Michael Anderson’s Family Structure in Nineteenth-Century Lancashire, 1971). Gender historians have put the spotlight on the family as the formative site in the acquisition of gender and sexual identities. This has involved a shift in research method, with a far greater emphasis on personal documents, such as letters and diaries (see, for example, Amanda Vickery’s The Gentleman’s Daughter: Women’s lives in Georgian England, 1998). The history of the working-class family still lags behind, because of the much greater scarcity of these materials.

Independence in South Asia and Africa

The period between 1945 and 1980 marked the end of the colonial era, after four centuries of European overseas expansion. All the colonial powers – Britain, France, the Netherlands, Portugal and Belgium – abandoned their colonies. In some cases they were forced to do so by national liberation movements; in other cases they withdrew with a good grace in the hope of retaining influence in the future. The British withdrawal from India and Pakistan in 1947 was marked by severe communal violence. The independence of Ghana in 1957 set in train a rapid sequence of decolonization, leading to independence for Nigeria (1960), Kenya (1963) and many others countries. Independence for Zimbabwe (1980) marked the end of this phase. Hong Kong was not handed over to China until 1997.

Lord Mountbatten swears in Jawaharlal Nehru as the first Prime Minister on an independent India on 15 August 1947.

Orientalism

In the eighteenth century European scholars developed a keen interest in the history and culture of the ‘Orient’, a concept they applied to an area ranging from North Africa and the Middle East through the Indian subcontinent to China and Japan. In his 1978 book Orientalism, the literary scholar Edward Said argued that this interest in fact reflected the Europeans’ sense of their own superiority over what they saw as a romanticized and ‘mysterious’ East.

- Edwardian suffragettes

- http://www.bbc.co.uk/archive/suffragettes/

- This collection from the BBC includes personal memories of women involved in the movement to win the right to vote in Edwardian Britain.

- Aristotle’s Masterpiece

- http://www.exclassics.com/arist/ariscont.htm

- This work, not actually written by Aristotle, was an early sex manual written in the seventeenth century, but was reprinted various times over the following centuries. This reprint is from the early twentieth century.

- A Vindication of the Rights of Women

- http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=rbc3&fileName=rbc0001_2008amimp11328page.db

- Mary Wollstonecraft’s 1792 work is one of the earliest feminist books. In the work, Wollstonecraft made analogies between the position of women in Western societies and the position of slaves.

- Ibn Battuta

- http://ibnbattuta.berkeley.edu/

- Ibn Battuta (1304–1368/9) was a Moroccan explorer who travelled throughout the Muslim world, which included much of Africa. His writings provide an early source for African history before the arrival of Europeans.

- Edward Said on Orientalism

- http://www.counterpunch.org/2003/08/05/orientalism/

- In this article written 25 years after the publication of Orientalism, Edward Said reflects on the book’s impact.

- Black Cultural Archives in Brixton

- http://www.theguardian.com/culture/2014/jul/29/black-cultural-archives-new-centre-brixton

- While black immigration in Britain did not get underway on a large scale until the 1950s, blacks have been in Britain since at least the sixteenth century. The Black Cultural Archives have recently opened in Brixton, in London, and aims to collect documents and other records of black history in Britain.

Memory and the spoken word

History is both a form of memory and a discipline that draws on memory as source material. Today some of the most productive discussions about the nature of history are pursued in this area. This chapter looks at the culture of commemoration before examining in more depth the practice of oral history, in which people are interviewed about their memories. Oral sources have had a major impact on social history, and on the pre-colonial history of Africa. Such material can give an exhilarating sense of touching the ‘real’ past, but it is as full of pitfalls and difficulties as any other sort of historical material. What questions should historians ask of oral material, and what role do they themselves play in its creation?

- What role have oral traditions played in preliterate societies?

- How should historians assess these traditions as sources?

- How do oral tradition and collective memory function in Western societies?

- How has historians’ use of oral history changed over time?

- What are the promises and pitfalls of oral history?

- Why has the study of memory emerged as a new area of inquiry?

Gathering oral history

As oral history has grown in popularity so historians have become more sophisticated in how they set about collecting reminiscences. Museums and archives specializing in the history of the twentieth century (for example, the Imperial War Museum) often invest in the gathering of oral memory interviews while potential interviewees are still alive. Television history has long made use of oral history interviews, often with figures who played a leading role in important events of twentieth-century history. Such important first-hand testimony can be invaluable, but it needs to be treated with caution: interviewees can be wanting to get ‘their’ version of events on record. Oral history societies publish handbooks to give advice to novices in the field. The oral history researcher needs to bear in mind that interviewees may be very elderly and frail, and unable to take being interviewed for any lengthy session. Few interviewees can launch immediately into detailed reminiscence about events they might not have thought about for years. Historians have learned the value of approaching the main theme of the research carefully, sometimes providing artefacts or music from the period to help to trigger the memory. Memory itself has to be treated with great caution. It can be remarkably clear, even after a very long time; on the other hand, memory can play tricks, and what seem to be firm and detailed memories can be disproved by other evidence.

Historians have learned the techniques required to get hold of the oral testimony of witnesses to the past. But how much care is needed in dealing with first-hand accounts that are inevitably influenced by hindsight? © Topfoto/Image Works.

Riots in Brixton in the 1980s

A number of riots occurred in the 1980s in various urban, predominantly black areas in Britain, the result of high unemployment, poor housing, and a distrust of police and local authorities. In April 1981, tensions flared in Brixton in London as police attempted to deal with street crime through application of the so-called ‘Sus’ law, which allowed police to stop and search anyone suspected of a crime. More than 1,000 people were stopped, and many black residents felt they were unfairly targeted. Rioting began in Brixton on 10 April over rumours of police brutality and the following day crowds had swelled, forcing a confrontation between rioters and police. Cars and businesses were burned and hundreds of people were injured before the rioting was contained in the middle of the night. Riots also occurred that summer in Liverpool (Toxteth) and Leeds (Chapeltown). In the aftermath of the rioting, an independent report found that in addition to the economic disadvantages racial minorities had suffered, police actions had been heavy-handed. The report did not however find the police ‘institutionally racist,’ a judgment that would be contradicted by another report the following decade. While police practices were overhauled, little was done to remedy the economic deprivation in these areas. Rioting again broke out in Brixton in September 1985, this time triggered by the shooting of a woman at the hands of police as they searched for her son on a gun offense. Rioting again lasted several days and spread to Tottenham in London, as well as Toxteth.

- Proposed Removal of the Henry Havelock statue from Trafalgar Square

- http://www.theguardian.com/uk/2000/oct/20/london.politicalnews

- In 2000 London mayor Ken Livingstone proposed (unsuccessfully) to remove the statue of Henry Havelock, a general during the 1857 Indian Mutiny, in favour of a more widely known figure.

- Federal Writers’ Project

- http://www.loc.gov/rr/program/bib/newdeal/fwp.html

- During the 1930s, the Federal Writers’ Project – a project originally funded by the US government to provide work for unemployed writers during the Great Depression – compiled local histories and undertook oral interviews. Part of the project was the Slave Narrative Collection, which comprised over 2,000 interviews with former slaves.

- British Library Sound Archive

- http://sounds.bl.uk/Oral-history

- The British Library contains a large collection of oral history recordings, some of which are available to listen to online.

- The People’s Autobiography of Hackney

- http://www.yeahhackney.com/catching-up-with-ken-jacobs-the-peoples-autobiography-of-hackney/

- An interview with Ken Jacobs, one of the original interviewees of the 1970s oral history project about the people of Hackney.

- Interviews of Anzacs

- http://www.australiansatwar.gov.au/throughmyeyes/w1_wwp.html

- This website contains a number of interviews with Australian soldiers who fought at the Battle of Gallipoli (1915) during the First World War.

Anzac troops charge a Turkish position during the disastrous Gallipoli campaign of 1915.

History Beyond Academia

History has a life beyond the university. Popular interest in the subject is evident in television, tourism, local history and reading tastes. This chapter considers the relationship between these popular forms and the academic kinds of study which have been the focus of this book until now. History beyond academia is now referred to as ‘public history’. Does it undermine historical scholarship, or should all approaches to the past be welcomed as dimensions of a common historical culture?

- What is public history? What do public historians do?

- How have concerns about ‘heritage’ evolved over time?

- Why are some historians ambivalent about public history? How can academic and public historians work together?

- How have historians engaged with the public through various media like television, newspapers, and the internet?

Development of the British Museum

The British Museum was founded in 1753. Most of its material came from the collections of the scientist Sir Hans Sloane (1660-1753), who bequeathed his nearly 71,000 objects – books, animal and plant specimens, artwork, and other artefacts from civilisations around the world – to King George II on condition of payment to Sloane’s heirs £20,000, a sum much less than the overall value of the collection. Initially George was unsure if sufficient funds were available, but appealed to Parliament for the money and MPs seized the opportunity to create a national museum. Three other libraries, the Cottonian Library (the collection of Robert Cotton (1571-1631)), the Harleian Library (the collection of Robert Harley, 1st Earl of Oxford and Earl Mortimer (1661-1724)), and the Royal Library (the collection of past monarchs), were added in short order, and with Sloane’s collection would make up the foundation of the museum’s holdings. The museum received further donations in the following decades and increasingly included objects acquired from Britain’s overseas empire. The location of Montagu House was chosen for the site of the museum and it opened, free of charge, to the public in 1759.

The British Museum, founded in 1753, established the concept of the public museum, funded by and accessible to the public.

- David Irving and Holocaust Denial

- http://www.hdot.org/en/trial/

- In 2000 David Irving sued author Deborah Lipstadt for libel for claiming that he was a Holocaust denier. This led to the unusual circumstance of the historicity of the Holocaust being determined in court.

- English Heritage

- http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/

- English Heritage projects are one of the main examples of public history through the preservation of historic sites and artefacts for the public.

- District Six Museum

- http://www.districtsix.co.za/

- The District Six Museum in Cape Town, South Africa, opened in the 1990s after the end of apartheid. The museum documents the stories of those forced out of their homes to make the area ‘white-only’.

- Carl Chinn

- http://www.carlchinnsbrum.com/

- Carl Chinn’s interviews with individuals in Birmingham reflect a democratic view toward oral history that seeks to record the lives of the least advantaged.

- Economic historians on the financial crisis

- http://www.theguardian.com/business/2010/mar/03/history-lessons-on-public-debt

- One way historians can contribute to the public debate is through letters to the editor, as in this case, where leading economic historians wrote to The Guardian on the importance of understanding the historical context of the financial crisis.

- History News Network

- http://historynewsnetwork.org/

- The History News Network is an important Internet resource which gives historians a platform to examine contemporary issues in their historical context.

- History and Policy

- http://www.historyandpolicy.org/

- History and Policy is another site that allows historians to offer their expertise on a variety of policy issues.