10.1 Making sounds, and writing them down

At various points in this book we shall be talking about consonants, vowels and diphthongs. There are many different linguistic perspectives from which these sounds can be described. The one we shall use here is based on how they are produced, or articulated. It is an articulatory perspective. It is also a traditional, as well as a much simplified, one – sound production in a very small nutshell.

The defining feature of consonants is that the sound is produced by air passing through an obstruction involving some of the organs we use to produce speech. Consonants can be classified according to three characteristics. One is which speech organs the obstruction involves. When you say the [b] at the beginning of the word ‘bit’, the speech organs in contact are your two lips. The sound is described as bi-labial, from the Latin word labium, meaning ‘lip’. In the case of the [t] at the beginning of ‘tip’, the organs involved are (in RP at least) the tongue and the hard ridge just behind your teeth, known as the alveolar ridge. The sound is classified as alveolar.

The second type of classification is according to the type of obstruction involved. In the case of [b] and [t], the obstruction is a complete one. For a short time, the lips (for [b]), or the tongue and the alveolar ridge (for [t]), come fully together. The sound is produced by the small explosion of air which occurs when the contact is released. This ‘explosive’ characteristic is captured in the name plosive, which describes these sounds. But there are various other types of contact possible. One is the kind of vibration created by the close proximity of two organs. An example is the [f] at the beginning of ‘fit’. This is not an ‘explosion’ but a ‘friction’, and the sound is classified as a fricative – a labio-dental fricative, in fact, because the organs involved are the bottom lip (the ‘labio’ part, and the top teeth (the ‘dental’ part).

The third classification in our traditional description is to do with voice. When you produce some sounds, your vocal cords vibrate, and these sounds are called voiced. An example is the [z] at the beginning of ‘zip’. But with some consonants, the vocal cords do not vibrate, and these are called voiceless. Voiced and voiceless consonants are often presented as ‘pairs’, and the voiceless ‘equivalent’ of [z] is [s], the sound at the beginning of ‘sip’. If you put your fingers on your throat when you say a voiced sound, you can perhaps feel a small vibration made by the vocal cords, which you do not feel for a voiceless sound. Other pairs of voiced and voiceless consonants are: [v] and [f], [d] and [t], [g] and [k].

Here are our three characteristics used to describe some of the consonants mentioned above:

- [b] is a voiced bi-labial plosive

- [t] is a voiceless alveolar plosive

- [z] is a voiced alveolar fricative

- [s] is a voiceless alveolar fricative.

This is, of course, just one small part of a complex picture. If you want to know more, there are various internet sites that have information, as well as innumerable elementary phonetics textbooks.

All English vowels are voiced, and what distinguishes them from consonants is that no major obstruction is involved; air passes relatively freely from the lungs out through the mouth. Because the shape of the oral cavity does much to determine the nature of vowel sounds, the position of the tongue plays an important role in categorising them. There are two dimensions involved: high/low, and front/back. Say the words ‘sit’ and ‘sat’ out loud to yourself. The vowels in these words are [ɪ] and [æ]. You can probably feel that the position of the tongue is higher for the first than for the second. The first is called a high vowel, and the second a low vowel – the terms close and open are also used, because the highness or lowness of the tongue makes the oral cavity smaller (more closed) or larger (more open). There are half-close and half-open vowels between these positions: the [e] in ‘bet’, for example. Now for front/back: words to say aloud here are ‘lee’ (with [iː]) and ‘loo’ (where the vowel is [uː]). Again, you will be able to feel the difference in tongue position, and understand why the first is called a front vowel and the second a back vowel. Between front and back lies central, and this is where our friend [ə] resides (this vowel is discussed in 10.2.2 and elsewhere). The third dimension is length – the amount of time that the sound is held. The symbol ‘ː’ is put after some vowels to signal that they are long rather than short. You will hear the difference of length if you pronounce ‘sit’, with its short vowel [ɪ], and ‘seat’, with its long [iː].

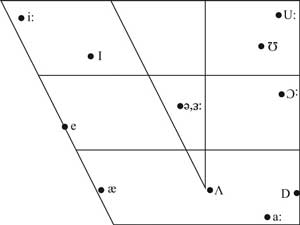

Because our description is articulatory, and the position of the tongue in the mouth is involved in two of the classification characteristics, it is possible to show vowels in a representative diagram of the mouth like the one below. The sharp pointy bit in the top left corner is the top front of the mouth, and the right angle at the bottom right corner is the lower back point of the mouth. The low front corner is slightly further back in comparison with the top front corner because most people’s lower front teeth and chin are further back than their upper lip and teeth. The horizontal lines in the diagram show how close or open a vowel is, while the vertical lines indicate whether it is front or back. Central vowels reside in the middle triangle. Sounds are represented by dots, which indicate tongue position.

English RP monophthongs

(approximate tongue positions)

What about diphthongs? Although long vowels are longer than short ones, the quality of the sound produced when saying a vowel does not change much. The result is one constant sound, and these vowels are called monophthongs (from the Greek monos meaning ‘single’). Diphthongs are different, because they involve a deliberate ‘glide’ from one vowel to another: the prefix di- in the name comes from the Greek dis, meaning two. Take the sound at the end of the word ‘now’, for example. It starts off as an [a] and moves to [ʊ]. It is a glide from a short close front vowel to a short close back vowel. The sound is written as [aʊ].

Is a diphthong one sound or two? The answer is ‘one sound with two elements’. In all important respects it functions as one sound. For example, in English, separate vowels indicate separate syllables. But ‘now’ is a one (not two) syllable word, precisely because the two vowels [a] and [ʊ] are treated as one sound. It is possible in English to find two vowels following each other without a joining glide. In such cases, the result is not a diphthong but simply two separate vowels next to each other. The word ‘reiterate’ is an example. It has the vowels [iː] and [ɪ] together, but they do not form a diphthong. The word has four separate vowels, and four syllables, not three.

We use phonetic transcriptions more than once in this book. These are written-down versions of speech. We will discuss in 12.2 the fact that the letters of our written alphabet can represent more than one sound, and for this reason, this alphabet does not give an accurate representation of pronunciation. You may want to take a look now at what the opening paragraph of 12.2 says on this matter. A phonetic transcription, using the symbols given on page xv, is far more accurate, because these symbols are (to a good extent) uniquely associated with separate sounds.

If you are new to phonetic transcriptions, you may find that they take some getting used to. First of all, to manage them easily, you need to be very familiar with the phonetic symbols. You may also at first find it difficult to keep in mind that you are not dealing with the world of writing, but of sounds. You will often find words which, though always written in the same way, can have more than one phonetic version – because they have more than one pronunciation. Take the word ‘the’ for example. It is always written in the same way, but it can be pronounced [ðiː] – as in ‘the end’ for example, and also as [ðə], in ‘the cat’. With phonetic transcription, you have to ‘think sound’ all the time.

Newcomers to transcriptions may like to try reading a few of them aloud. They are easy to find on the internet. Try Lingorado for example. It allows you to input your own text. Be sure, if you use this site, to check the ‘show weak forms’ button before starting. You could also try reading the RP version of the Prologue to Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. The transcription is given in Chapter 14, Figure 14.1.

10.2 Strong verbs behaving badly

Here is the list of the seven OE strong verb classes, given in Table 6.4:

| Class | Infinitive | Past singular | Past plural | Past participle |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | rīdan (‘ride’) | rād | ridon | geriden |

| II | clēofan (‘cleave’) | clēaf | clufon | geclofen |

| IIIa | findan (‘find’) | fand | fundon | gefunden |

| IIIb | helpan (‘help’) | healp | hulpon | geholpen |

| IV | stelan (‘steal’) | stæl | stǣlon | gestolen |

| V | tredan (‘tread’) | træd | trǣdon | getreden |

| VI | scacan (‘shake’) | scōc | scōcon | gescacen |

| VII | blōwan (‘blow’) | blēow | blēowon | geblōwen |

OE strong verbs underwent many changes in ME, with classes becoming mixed and different forms merging. Here are two OE → ME changes:

As you can see, in OE Classes II, IIIb and IV (among others), the vowel is different in the past plural and the past participle; so you have clufon and geclofen, for example.

In ME verbs coming from these OE classes, the vowel of the past participle came to be used in the past plural too; so for the ME verb cleven, instead of cluven you have cloven.

Given this change, what would be the past plural forms of the ME verbs helpen, stelen, and the ME crepen (from OE Class II crēopan – ‘creep’, which conjugates like clēofan)? The answer is given below.

- In ME, the vowel in Class V participles becomes the same as in Class IV participles. So OE getreden becomes ME ytroden. What then happens to Class V, the verb participle which would otherwise have been yspekan (from speken ‘speak’)? Answer below.

(i): holpen, stolen and cropen; (ii): yspoken.

10.3 Covering your head

The Pastons were a family of Norfolk gentry who wrote a series of letters to each other between 1422 and 1509. Theirs is the largest surviving collection of ME letters. Here is part of one written in 1448 by Margaret Paston to her husband, John. It describes an argument between the Pastons’s chaplain, James Gloys, and a family rival, John Wymondham. The argument starts because Wymondham tells Gloys to cover his head, which good behaviour requires. But good behaviour also requires that someone should raise their hat to greet a superior – hence Gloys’s response and the anger that it causes. The argument turns rather nasty after this extract, and several swear words look as if they may possibly have been scratched out of the text:

Jamys Gloys hadde ben in þe toune and come homward by Wymondams gate. And Wymondam stod in his gate, and John Norwode his man stod by hym, and Thomas Hawys his othir man stod in the strete by þe canell side. And Jamys Gloys come with his hatte on his hede betwen bothe his men, as he was wont of custome to do. And whanne Gloys was a-yenst Wymondham, he seid þus: 'Couere thy heed’ And Gloys seid ageyn, -So I shall for the.’ And whanne Gloys was forther passed by þe space of -iii or iiij strede, Wymondham drew owt his dagger and seid, 'Shalt þow so, knave?' And þerwith Gloys turned hym, and drewe owt his dagger and defendet hym, fleyng in-to my moderis place . . .

a-yenst – opposite |

iiij = 4 |

strede – strides |

Note that the word order is very much as it would be today, with the possible exception of the clause: as he was wont of custome to do, where a preferable PDE order might be as he was wont to do by custom. There is one example of SV inversion – 'Shalt thow so? – which, because it is a question, you would find in PDE also.

The text is taken from Davis (2004: 224).

10.4 A particularly moral dative?

In Latin there was a construction known as the ‘dativus ethicus’, used to signify that the person mentioned had a particular interest in what was being talked about, or was particularly affected by it in some way. ‘Dativus ethicus’ became ‘ethic(al) dative’ in English. The word ‘ethic’ here does not mean ‘moral’ but something like ‘emotional’ – because a personal emotional involvement is indicated. The construction first appeared in ME, and is found in the work of Chaucer. In The Knight’s Tale, for example, a character says: Now to the temple of Dyane the chaste,/ As shortly as I can I wol me haste. Another possible example from The Pardoner’s Tale is: he wole him no thing hyde. Me and him are ‘ethic datives’.

The construction was still found in the eighteenth century. Here is Henry Fielding, in his novel Tom Jones (X.iii.475): as wholesome as the best champagne in the kingdom . . . and they drank me two bottles.

You also find versions of this curious construction today, in sentences like ‘I must get me a wife’. Some say that a modern equivalent is sometimes the phrase ‘for me’, added politely to a request or instruction and indicating that sense of ‘particular interest’. This is in common use among nurses, who might ask someone ‘Pop this [e.g. thermometer] in your mouth for me’. It makes the request sound like a personal favour rather than an imposition.

The ethic dative was particularly common in EModE times, and is found not infrequently in Shakespeare. You will find an example of it in 13.4’s ‘buckrom story’, when Falstaff says I followed me close. On one occasion, in The Taming of the Shrew, a joke is constructed around its use. Petruchio wants his servant Grumio to knock on the door of a house. Knock me at this gate, the master says, using the ethic dative. Grumio, doubtless disingenuously, interprets this to mean that he should ‘knock’ (hit) Petruchio when they reach the gate, which he duly does. Petruchio is not amused and punishes the servant, who protests thus: O heavens! Spake you not these words plain, ‘Sirrah, knock me here, rap me here, knock me well, and knock me soundly ’? He was, he says, just obeying orders.

10.5 The past in the present

The ME period also saw the development of the so-called historic present tense. This is when a present tense is used to describe past actions. You can find an example of this in the opening paragraph of section 10.3, where a continuation of the Chaunticleer story is given. The events were, of course, in the past, but the story is told in the present. This practice is first recorded in the Early Middle English period. One explanation for this use of the tense is that it makes narrative sound more vivid – as if it were happening at the present time. Mick Short (unpublished) puts forward another explanation. He points out that the present tense is used for commentary (in football matches, for example), where a commentator is between the listener and the events being described. Often in narratives, the historical present has a similarly ‘distancing effect’, Short argues.

Storytellers like Chaucer (and later Dickens) use it. In The Canterbury Tales, it is particularly found in The Knight’s Tale and The Man of Law’s Tale. One of the characters in the latter is King Alla, and these lines describe, in the historic present, his return home: Alla the kyng comth hoom soone after this/ Unto his caste!, of the which I tolde,/ And asketh where his wyf and his child is. The use of this tense is sometimes controversial today, with some arguing that ‘past events should be told in the past tense’.

10.6 Chaunticleer escapes

(a) Here is a recording of the ME version:

A phonetic transcription of this recording:

ðə fɒks ænswɜːrd ‘in faɪθ it ʃæl beɪ dɒn’

ənd æz heɪ spaːk ðæt wɜːrd æl sɒdeɪnliː

ðɪs kɒk braːk frəm ɪz muːθ dəlivrɜːliː

ənd haɪx əpɒn ə treɪ heɪ flaɪx ənɒn.

ənd wæn ðə fɒks saʊx ðæt ðə kɒk wəz gɒn

‘əlaːs’ kwəʊt heɪ ‘əʊ ʃæntəkleɪr əlaːs

iː hæv tʊ juː kwəʊt heɪ iːdɒn trespaːs

. . . . .

Bət siːr, iː dɪd ɪt ɪn nəʊ wɪk əntentə

Kɒm duːn, ənd iː ʃæl tel juː wɒt iː mentə’

(b) A recording of the RP version:

A phonetic transcription of this recording:

ðə fɒks ɑːnsəd ‘in feɪθ it ʃɑːl biː dʌn’

ənd æz hiː speɪk ðæt wɜːd ɔːl sʌdənli

ðɪs kɒk brəʊk frəm ɪz maʊθ delivrəli

ənd haɪ əpɒn ə triː hiː fluː ənɒn.

ənd wen ðə fɒks sɔː ðæt ðə kɒk wəz gɒn

‘əlæs’ kwəʊθ hiː ‘əʊ ʃæntəklɪə əlæs

aɪ hæv tʊ juː kwəʊθ hiː iːdʌn trespæs

. . . . .

bət saɪə, aɪ dɪd ɪt ɪn nəʊ wɪk əntent

kʌm daʊn, ənd aɪ ʃæl tel juː wɒt aɪ ment’