Students

Historical research tends to disregard the fortuitous concurrence of events that happen in widely separated parts of the world. Historians look for patterns and relations, and for their (structural) development and change through time, not for chance or contingency. Introduction to Medieval Europe 300–1500 is no different in this respect. It aims to present Europe’s medieval history in broad outlines by highlighting the main socio-economic, political, religious, cultural, intellectual and ideological features of the centuries between 300 and 1500, which should enable the reader to get a coherent picture of that period.

And yet we remain fascinated by synchronicity, not in the stricter, Jungian sense which claims that causally unrelated events can share meaning on a collective subconscious level, but seen from a more general historical perspective which discloses that causally unrelated events sometimes converge in their effects and in that way become concurrent causes of later developments. The invasion of the Langobard army in Italy in 568 was in no way related to the birth of the Prophet Mohammed in Mecca in about the same time, but in the longer run both events turned out to have dramatic consequences for Italy’s history. Drawing attention to such concurrences is another way of gaining a better, more detached appreciation and understanding of the past. That is why the timeline on the website is conceived with the purpose of adding synchronicity as a feature to the ‘normal’, comparative-diachronic timeline printed in the book.

The synchronic timeline works very simply. For each of the twelve centuries between 300 and 1500 a range of one to seven years has been selected, for which concise data on a limited number of ‘typical events’ from various parts of Europe (and often far beyond) that have no direct connection are brought together. They are intended first of all to surprise and to nourish a taste for the unexpected but, more importantly, to stress the importance of always holding on to a wide geographical scope. As they may also make it easier simply to memorise important facts, the textual information for each of the twelve synchronic nodes is supported by suitable illustrations and references to digitised maps.

The fourth century: the year 379

In the year 379, Theodosius, the 32-year-old son of a Spanish general, came to power during the months of chaos and crisis that followed the Roman defeat against the Tervingian Goths at the battle of Adrianople (378). He was appointed emperor in the East, and would not be the sole ruler of the Roman Empire until 392 (de facto 388). The new emperor’s first concern was to deal with the Goths. It would take several years before a satisfactory settlement was reached and peace restored. Under these circumstances, the political fate of Theodosius depended much on the absence of hostilities with Rome’s long-standing arch-enemy in the East: the ‘New Persians’.

Close to the western Iranian town of Kermanshah, halfway between Baghdad and Teheran, a series of impressive reliefs, cut out of the Zagros mountains, glorifies the deeds of the Sassanian dynasty that ruled Persia. One of these reliefs depicts the crowning ceremony of Ardashir II, who succeeded his half-brother Sapor II as shahanshah (‘king of kings’) in the same year as Theodosius became emperor. In the relief, the new shah is approached by the Persian god Mithras (to the left) and a figure believed to be either the god Ahura-Mazda or Ardashir’s predecessor, Sapor (or both!). He passes on to the shah the ring of power. Under the shah’s feet is the slain body of the Roman emperor Julian, who had been defeated by Sapor II in 363. Despite the strong anti-Roman feeling expressed by the relief, and despite a bloody confrontation between Romans and Persians at the beginning of Ardashir’s reign, the new shah understood that an enduring peace with the Romans was vital for the maintenance of Sassanian rule, so negotiations were started. Ardashir had already died when the treaty was finally ratified. However, its effects were long-lasting. It would not just save the regime of Theodosius, but inaugurate an extended period of peace with the (East) Romans, which would only end in 502.

Although Theodosius himself converted to Christianity only after he had been proclaimed emperor, he became the first Christian emperor who would no longer tolerate other religions in the Empire. He took great pains over the persecution of heretics and non-Christian ‘pagans’. Initially, this incited much resistance. For example, also in 379, the newly appointed patriarch of Constantinople, Gregory Nazianzus (aka the Theologian), was attacked and injured by an Arian ‘mob’.

Byzantine icon of Three Greek Fathers of the Church (from left to right: Saint Basil, John Chrysostom, and Gregory of Nazianzus).

Missorium (ceremonial silver dish) of Theodosius.

Taq-e Bostan relief in the Zagros mountains.

Taq-e Bostan relief in the Zagros mountains.

The fifth century: the years 450–455

In the year 450 the East Roman emperor Theodosius II died after a fall from his horse. His name is chiefly connected with his publication of the Codex Theodosiana, a compilation of Roman law that preceded the more famous Corpus Iuris Civilis, issued about a century later by the emperor Justinian. In the same period, Attila, sole khan of the Huns, prepared an invasion of Gaul, which ended in 451 near Châlons-en-Champagne in the great battle of the Catalaunian Plains. In the same year another great battle took place in Asia Minor, near the present-day enclave of Nakhichevan, in which a large Armenian army was defeated by the Sassanian shah Yazdegerd. Afterwards, the kingdom of Armenia would never regain its former size and power. However, while denying Jews the right to practice their religion, the shah respected Christianity. This would secure the survival of the Christian Church in eastern Anatolia.

Also in 451, and also in Asia Minor (but in the western, Roman part) a tricky issue in Christian doctrine, the dogma of the Holy Trinity, was finally decided upon at the Council of Chalcedon. How soon this news arrived in Ireland, at the other extreme of the Roman world, where two legendary missionaries, Patrick and Palladius, were active at the time, we’ll probably never know.

Equally legendary is the meeting of Pope Leo I with Attila, who invaded Italy in 452. The Hun’s total destruction of the city of Aquileia near the mouth of the Torre River instigated the foundation of a better-protected settlement in a lagoon area further to the west. This would grow into one of the largest and most magnificent cities of medieval Europe: Venice. Attila’s quick retreat was more likely to have been caused by disease in the Hunnic army than by papal pleading.

The years 453–455 were dreadful and murderous. One after another, the great leaders of the West died: first Attila, then the Roman commander in the West, Aetius, then his murderer, the emperor Valentinian III, and finally Valentinian’s short-lived successor, the scheming senator Petronius Maximus. Chaos and war reigned, both in the dwindling Hunnic steppe empire and in the Roman West. In August 455 a Vandal army, led by the old king Gens

Bust of the emperor Theodosius II from the Louvre Museum collection.

Croagh Patrick in County Mayo, one of the most dramatic sites in Ireland, associated with the activities of Saint Patrick.

Each year, thousands of pilgrims make the steep climb to the sanctuary on the top.

The legendary meeting of Pope Leo I and Attila as painted al fresco by Raphael in the Stanza di Eliodoro in the Vatican palace in 1514.

The historical meeting of the East Roman historian Priscus with Attila as depicted by the Hungarian nationalist painter Mór Than in 1870.

Bust of Valentinian III, the last emperor from the House of Theodosius.

Satellite view of Venice, taken in 2008.

Sack of Rome in 455 as imagined by the Russian Romanticist painter Karl Pavlovich Briullov around 1835.

The sixth century: the years 565–570

The year 565 saw the death of the great Byzantine emperor Justinian. His marriage to Theodora, a much younger actress of ill repute, had not produced any children, so Justinian was succeeded by a nephew, Justin II. In spite of his remarkable successes in recovering Roman territory in the West, Justinian left behind a state that was still far removed from the ideal of Pax Romana (‘Roman Peace’). It is true that on the eastern front, after years of warfare, a 50-year truce had been concluded with the Sassanian shah in 562, but a new and greater threat emerged with the appearance of the nomadic Avars in the western steppes. They were remnants of the Jou-Jan (or Rouran or Nirun) khaganate that had built up an impressive empire in the Mongolian steppe until it was annihilated by the confederation of the so-called Blue or ‘Heavenly’ Turks (Göktürk). The Avars penetrated through the lower Danube area into what is now called the Hungarian puszta or steppe soon after the middle of the sixth century, where they were faced with Germanic speaking peoples such as the Gepids and the Langobards. In a set of events as yet ill understood, but taking place soon after Justinian’s death, the Avars probably supported the Langobards in their war against the Gepids, on condition that they would leave the steppe lands to the Avars. That is exactly what happened. Right after their great victory over the Gepids in 568, the Langobard ‘army’ left its homeland and invaded Italy. The historical consequences were far-reaching: while the larger part of Italy would come under Langobard or Lombard rule for centuries, the Avar khaganate became the dominant power on the Pontic steppe and in central and south-east Europe, giving the Byzantine Empire a new and dreaded enemy. One other result was the stealthy but continuous penetration of the Balkans and western Greece by small bands of Slavonic speaking peoples. They also were the Avars’ closest allies, to the point where the Avars changed their language from Altaic to Slav.

Far to the south east of these European developments, but at exactly the same time (although the events were in no way connected), something took place that would alter world history: the birth of the Prophet Mohammed in the Arabian city of Mecca.

Portrait of the emperor Justinian in one of the famous mosaics on the walls of the San Vitale church at Ravenna. The mosaics were created in 547, when Justinian must have been about 65 years old

Drawing from Avar graves showing horsemen, arms, decorations and spurs.

Drawing from Avar graves showing a novelty from the eastern steppe that the Avars introduced into Europe.

Allegedly, the Langobard king Alboin offered his wife, the fair Rosamund, daughter of the Gepid king Kunimund, a drink from her father’s skull. Ink drawing from the nineteenth century.

Langobard ruler on coin.

View of Mecca: great mosque of Mecca and its hundreds of thousands of pilgrims dwarfed by skyscrapers.

The seventh century: the years 660–665

In the year 660, members of the Pippinid family, the ancestors of Charlemagne, staged their first coup d’état in Merovingian Francia. Grimoald, son of Pippin of Landen and mayor of the palace – the king’s chief advisor – in Austrasia, together with his brother-in-law Ansegisel had the old king of Austrasia, Sigebert III, adopt Grimoald’s son, Childebert, and put Childebert on the throne after Sigebert died. The scheme did not last very long however, and all three Pippinids were executed in 662.

In that same period the steppe lands north of the Black Sea were shaken by a power struggle between two Turkic-speaking groups trying to fill the power vacuum that was left behind by the dwindling hold of the Avars over the area. The Khazars won; they became the masters of a powerful steppe empire centred around the lower Volga. The losers were the Bulgars of khan Kubrat, who shortly after 660 moved in large numbers to the lower Danube region and thence into the Balkans, and into the northern part of the Byzantine Empire. This was the beginning of the very successful ‘First’ Bulgarian Empire, which would last from 680 to 1018.

While in 664 at the council of Streonashalh, near Whitby, the fate of the Anglo-Saxon church was decided – it became definitively Roman rather than Irish – Muslim armies penetrated into Afghanistan (where Kabul was conquered in 665) and Libya.

Golden tremissis with the image of the short-lived Pippinid king of Austrasia, Childebert III ‘the Adopted’.

Heroic equestrian statue of the founder of the first Bulgarian Empire, Asparuch.

Asparuch’s successors were eternalised in the rocks of the holy site of Madara. The horseman (a Bulgarian khan?) tramples a lion.

Ruins of the first Bulgarian Empire’s capital Pliska that may have had more than 100,000 inhabitants at the height of its power.

The monastery of St Hilda at Streonashalh near Whitby.

Afghan craftsmen between the fourth and seventh centuries chiselled two giant Buddhas from the sandstone rocks flanking the Silk Road through the Bamiyan Valley connecting Afghan Kabul with India. The statues survived the Arab-Muslim invasion of the 660s, but not the attack by the Taliban in 2001.

The eighth century: years 750–755

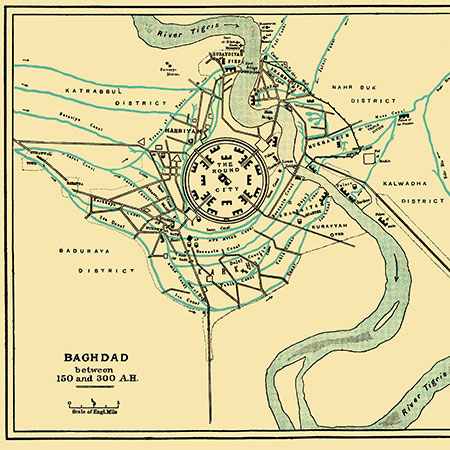

In the years 750–754, two political revolutions of great historical importance took place. First, in 750, Abu-Abbas al-Saffah (‘the blood spiller’), a direct descendant of the Prophet Mohammed’s youngest uncle, led a revolt against the Ummayad caliph in Damascus from eastern Iran. The rising succeeded thanks to the broad political and military support for Abu-Abbas’s case among both the Arab and Iranian elite. Abu-Abbas proclaimed himself the new caliph, the first in line of a dynasty that would formally hold to the caliphate until 1258. He moved the administrative centre of Arab-Islamic power further to the east, to the city of Kufa on the Tigris river. Soon afterwards the building of an entirely new capital started, which would become Baghdad.

Several months after this momentous event, a similar revolution took place in the Latin Christian West. In 751, Pippin the Short, long-time mayor of the palace who finally unified the kingdoms of the Franks, had the last king from the Merovingian dynasty, Childerik, deposed, and himself anointed and crowned with the support of the Roman pope. He was the first in line of the famous royal dynasty of the Carolingians.

King Pippin’s major military activities were his campaigns against the Arab-Muslim occupation of a number of cities and strongholds in Provence and Septimania (present-day Languedoc). Clearly, Pippin took advantage of the political turmoil in Arab-Muslim Andalus (Iberia) following the Abbasid revolution in the East, and he was not the only one. In 755, the Cordovan governor Yusuf al-Firi led an army against the Basques of Pamplona, and was defeated. Abu-Abbas himself, who died in 754, had been luckier against a formidable enemy appearing in Central Asia. In 751, an Abbasid armed force led by Ziyad ibn Salih blocked the advance of a Tang-Chinese army under the command of general Gao Xianzhi at the Talas river in present-day Kyrgyzstan. Chinese revenge was prevented by the outbreak in China, in 755, of the atrocious and protracted An Lushan or An Shi rebellion. In crushing that rebellion, the Tang emperor would have made use of Arab mercenaries, put at his disposal by the second Abbasid caliph, Abu-Abbas’s brother and successor, Al-Mansoer.

Manuscript page from the Tarikhnama (‘Book of History’) of Balami, written in 963 and known as the oldest prose work in the New Persian language. Balami was a Persian aristocrat who served the Samanids, the dynasty that ruled Iran during the ninth and tenth centuries, as vizier. The picture shows a page from a fourteenth-century manuscript of the Tarikhnama which describes the proclamation of Al-Saffah as caliph.

Plan of the original, perfectly circular structure of the new city of Baghdad.

Artist’s impression of early Baghdad.

Pippin the Short (the shorter man on the left) and his son Charlemagne (the taller man on the right) ‘offer’ the abbey of Prüm to God. Illustration in the thirteenth-century copy of the polyptych (list of possessions) of Prüm, drawn up by abbot Caesarius in 893.

Current view of the Talas river in Kyrgyzstan.

The ninth century: the years 874–879

While Viking settlers from Norway had found their way to the uninhabited isle of Iceland in the year 874, a ‘great army’ of Danish invaders was roaming England, spreading death and destruction. In 878 a decisive battle against the Anglo-Saxon army of King Alfred of Wessex was fought at a place called Ethandun (now Edington, Wiltshire). The Vikings lost. It paved the road to the conclusion, at an uncertain date, of a comprehensive treaty between Alfred and the Viking leader Guthrum, which divided the spheres of influence of the Danes and the English, with an old Roman road as a linear borderline.

The year after Edington, 879, saw the death of another legendary Viking chieftain: Rurik of Sweden, who had successfully penetrated the Volga basin with his retinue. The subdued Slav-speaking local populations called the Swedish Vikings ‘Rus’ (probably meaning ‘rowboatmen’). The Rus were there to stay, attracted by the wealth of the Arab world further south. Rurik’s son Oleg moved his power base to the west, to a place called Kiev, on the Dniepr river.

In the autumn of 877 Charles the Bald, king of the West Franks, and since 875 also king of Italy and Roman Emperor, died on his return from Italy to France on the descent of the Mont Cenis pass in a spa – now skiing resort – called Brides-les-Bains. Should Charles have lived longer, Italy and the imperial crown might have passed for good to the kings of West Francia (the later kingdom of France). Further west, in Viking-infested England, Charles’s old friend and long-time intellectual guide, John Scotus Eriugena (‘John the Scot born in Ireland’), passed away in the abbey of Malmesbury. Eriugena was considered by many to have been the greatest scholar of his age. Others, however, considered him to be a dangerous magician with suspect, heretical ideas.

Also in 877, an army of the caliph of Baghdad, al-Mu’tamid, tried to expel the rebel Turkic general Ahmad ibn Tulun from Egypt, where he had seized power – which makes him the first of many rulers of Turkic extraction in the Arab-Muslim world. Ahmad successfully fought off the caliph’s army and further extended his power over Syria. This was the beginning of the autonomous Tulunid emirate, which would last until 905.

Sólfar (‘Sun voyager’). Aluminium sculpture by Jon Gunnar Arnason in Reykjavik harbour commemorating the arrival of the Vikings in Iceland.

Reconstruction of Viking farmstead on Iceland; statue of Alfred the Great at Winchester (capital of Alfred’s kingdom of Wessex), made by the British sculptor Sir William ‘Hamo’ Thornycroft in 1899, a thousand years after Alfred’s death.

Sculpture of Viking ship with three Viking warriors in the city park of Kiev, fully recognising the Viking Rus as the founders of Kiev; Charles the Bald enthroned as king, manuscript illustration from 869 (Paris, BnF, Mss Latin 1152, f. 3v).

Charles the Bald enthroned as king, manuscript illustration from 869 (Paris, BnF, Mss Latin 1152, f. 3v).

Royal seal of Charles the Bald, 847.

Ink drawing of John Scotus Eriugena in a twelfth-century manuscript copy of Clavis Physicae, a book on physics by Honorius of Autun, in which ample use is made of Eriugena’s work (Paris, BnF, Mss Latin 6734, f. 3).

Map of the Tulunid emirate in Egypt and Syria (868–905).

The tenth century: the years 962–969

These were years of royal hopes and royal defeat, starting with the coronation of Otto I, king of Germany and Italy, as Roman Emperor in St Peter’s basilica in Rome (962). A short while later, in 963, and while Otto was busy subjecting the ‘duke’ of Poland, Mieszko (who was forced into paying tribute and into being baptised), a brilliant Byzantine career general named Nikephoros Phocas was pushed forward after the unexpected death of emperor Romanos II to become the joint emperor of Byzantium with Romanos’s two minor sons, Basilios and Constantine. Six years later, in 969, Phocas, described by the Italian bishop-diplomat Liutprand of Cremona as ‘a monstrous, fat-headed pygmy with the eyes of a mole’, was murdered by his nephew, John Tzimiskes – also a quite capable military man. He took over his uncle’s mistress, Romanos’s widow, Theofanu, and then his position as co-emperor.

In the meantime, the western emperor Otto in his turn had deposed Pope Benedict V in favour of a man of his choosing: scion of a noble family from Rome who took the name Pope Leo VIII. Leo would die less than a year later, two years before Otto, in 967, had his eponymous son and future successor, Otto II, crowned as co-emperor in Rome by Leo’s successor Pope John XIII.

The same years, 966–967, saw the birth of two royal princes who were both destined to become great rulers although neither succeeded in fulfilling this promise. Louis, the son of Lothar III, king of the West Franks, would reign for only 14 months as the last ruler in the West who descended directly from Charlemagne. He died at age 20 in 987. Due to the insignificance of his reign he was nicknamed Louis V ‘Le Fainéant’ (‘who did nothing’). In contrast, his counterpart Aethelred II, son of King Edgar of England, would rule over England for almost 40 years, from 978 to 1016 to be precise, but his reign was steeped in disaster. It was characterised by lost battles against the Danes, protracted periods of Danish raids ending in large-scale invasion, and a foolish attempt to deal with the Danes in England once and for all by staging a bloody day of reckoning. All this misfortune earned Aethelred the nickname ‘the Unready’, which means much the same as ‘ill-advised’.

In the east, the descendants of the Viking Rus were waging their own life-and-death struggle. After the Rus ruler of Kiev, Sviatoslav, had first invaded the Khazar steppe empire in 965, ending Khazar power over the western steppe, and then proceeded to conquer Bulgaria, the emperor of Byzantium, alarmed, paid the Turkic confederation of the Pechenegs to lay siege to Kiev, which they did in 968. After having solved this problem, Sviatoslav continued campaigning against Bulgaria – with the aid of Pecheneg mercenaries. Several years later, while planning to attack the Pechenegs on the steppe, he was ambushed and killed.

The most spectacular, and historically far-reaching, event of 969 happened in Egypt, which was invaded from the west by the army of Al-Mu’izz li-Din Allah, fourth caliph of the Berber dynasty of the Fatimids (‘descendants of [the Prophet’s daughter] Fatima’). The Fatimids had extended their power over Muslim Ifriqya (present-day Tunisia and Algeria) from the beginning of the tenth century, and taken on the title of caliph in 921. After their successful invasion of Egypt they moved their centre of power to their headquarters just north of the city of Fustat on the Nile; they called it al-Qahira (Cairo), ‘the Victorious’, a reference both to their astounding military success and to the planet Mars, which had been high in the sky at the moment of decisive battle. Because the Fatimids were Shi’ite Muslims, the new Egypt became a Shi’ite state until the fall of the Fatimid dynasty in 1171.

The German king/emperor Otto I and his wife Adelheid of Burgundy. Statues in polychromed stone on the interior wall of the choir of Meissen Cathedral, Germany – Otto and Adelheid founded the diocese of Meissen.

Coronation of King Louis V le Fainéant as depicted in a fourteenth-century manuscript of the Grandes Chroniques de France.

Gold coin with the head of King Aethelred II the Unready from c.1005.

‘Glorious entry’ of the emperor Nikephoros Phokas in Constantinople, 963, as depicted in a thirteenth-century manuscript copy of the chronicle of John Skylitzes, which covers Byzantine history of the years 811–1057.

Pechenegs attacking Kiev, 968, as depicted in the so-called Madrid manuscript copy of the same chronicle of John Skylitzes.

Gold coin struck by caliph al-Mu’izz in Cairo, 969, after his conquest of Egypt.

Map of old Cairo, with the citadel (military headquarters) to the south-east, and old Fustat to the south, opposite the Gizeh plateau.

The eleventh century: the years 1064–1066

In 1064, the Seljuq sultan Alp Arslan conquered Armenia and Georgia before invading, in 1068, Byzantine Anatolia (Asia Minor), to devastating effect. In the same year 1064, the reformer Pope Alexander II (1061–1073) sent the papal banner to Duke William of Aquitaine, who had put himself in command of a large army of knights ‘from France and Burgundy and other peoples’. Its target was the Iberian peninsula. Duke William wanted to give military aid to the king of Aragon in his struggle against the Muslims, who were advancing against the Christian principalities in the north of Spain. The knights were moved to their supportive action by fiery sermons by Pope Alexander and the abbot of Cluny. They insisted that liberation of Christian lands that had been occupied by Muslims was of ‘utmost necessity’. The major feat of arms was the siege and capture of the town of Barbastro in the southern foothills of the Pyrenees. It has often been seen as the start of the Reconquista, if not of the Crusades.

Among the ‘peoples’ in the army of William of Aquitaine most certainly of prominence was the Norman ‘race’, because this was the era of the Normans, the masters of political power play in eleventh-century Europe. Also in 1064, and inspired by the same spirit of holy war against Islam, Pope Alexander sent a second papal banner to the Norman warlord Roger of Hauteville, who three years earlier had crossed the Strait of Messina with his private army with the aim of conquering the isle of Sicily, that had been in Muslim hands since the beginning of the ninth century.

Of course, the most significant Norman success story started two years later, in the early days of 1066, when the English king Edward the Confessor died without leaving any offspring. Less than a week later England’s most powerful aristocrat, Earl Harold Godwinsson, was crowned as Edward’s successor, but this bloodless take-over of power was defied at once by two other candidates, both reputable warriors: the king of Norway, Harald Hardrada, and William, Duke of Normandy. Their relentless struggle came to a head in the course of three weeks at the beginning of autumn, when three battles were fought on English soil which would decide over England’s fate. Each of the competitors won one – Hardrada beat the English at Fulford; Earl Harold beat (and killed) Hardrada at Stamford Bridge; Duke William beat (and killed) Earl Harold at Hastings – but only the last winner took all. For reasons not entirely clear, Duke William, at the battlefield of Hastings, flew the papal banner.

Understandably, other events in 1066 are overshadowed by Hastings, but they are still important: the grant of a written charter to the town of Huy on the Meuse (the earliest north of the Alps), the horrifying pogrom against the Jewish community of Muslim Granada, and the irreparable Slav destruction of Hedeby, once the centre of long-distance trade between the Scandinavian and the Frankish worlds.

One of many representations of battles between Christians and Muslims during the Reconquista. Miniature from a thirteenth-century copy of the Cantigas de Santa Maria.

‘Duke Roger’, probably Roger Borsa, Duke of Apulia, son of Robert Guiscard, brother of Roger of Hauteville. Drawing from the manuscript of Peter of Eboli’s Liber in honorem Augusti (1196).

Harald Hardrada (in red, with royal crown) fighting at the battle of Stamford Bridge. Miniature from copy of Matthew Paris, Life of King Edward the Confessor (c.1250).

Overview of the modern display of the Bayeux tapestry in the Bayeux Tapestry Museum.

Scene from the Bayeux tapestry showing a messenger approaching Duke William who is holding the papal banner (second scene from the left).

The town of Huy, near Liège, on the confluence of the rivers Hoyoux and Meuse. There is a marked contrast between the steep rock on which the bishop’s castle and church once stood (now a fortress built in the nineteenth-century), and the lower town on the river shore, where the merchants’ and artisans’ quarters were.

Aerial photo of the medieval location of the town of Hedeby on the medieval border between Germany and Denmark.

The twelfth century: the years 1143–1144

The year 1143 saw the death of prince Yelü Dashi (or Yeh-lü Ta-shih), who had fled China after the collapse of the Liao, the dynasty of nomadic Kitan origin that had ruled northern China since the beginning of the tenth century and into which Yelü Dashi had been born. In a series of heroic events Yelü Dashi had escaped to the Mongolian steppe with a large army of followers. On the western extensions of the Mongolian steppe he created a huge empire that became known as the empire of the Xi Liao (‘Western Liao’) or khanate of the Qara Kitan (‘the Black Khitan’). Under Yelü Dashi it would pose a serious threat to Seljuk power in the Middle East. For that reason, western legend would transform the Kitan khan into the ‘priest-king John’ (Prester John), a mysterious Christian ally from the Far East, who was first mentioned in a German source in 1145. The actual Yelü was succeeded by his wife, princess Tabuyan (T’a-Pu-Yen). For a period of six years she acted as a regent for their grandson who was still in his minority, and during that time she must have been one of the most powerful women in the world.

One year after Yelü’s death, in 1144, the Turkic lord of Mosul and Aleppo, Imad ad-Din Zengi, stormed and conquered the town of Edessa, now in northern Iraq, then the capital of one of the small so-called crusader states that had been founded during the First Crusade. The outrage in Latin Christendom was great, and a new crusade was preached, most famously by the militant Cistercian leader Bernard of Clairvaux. From 1145 on, various crusader armies would depart to the East; the largest two were led by the German king, Konrad III, and by the king of France, Louis VII, who was accompanied by his wife, Eleanor of Aquitaine. The whole enterprise turned into a fiasco.

Also in 1144, Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou, assumed the title duke of Normandy on behalf of his wife, the empress dowager Mathilda, daughter and heiress to the English king Henry I. This can be seen as the hesitant start of what would grow into the Angevin Empire under Geoffrey and Mathilda’s son, Henry Plantagenet, who was recognised as king of England in 1154, two years after he had married Eleanor of Aquitaine.

Without a doubt, on 11 June 1144, Eleanor, then still queen of France, will have attended the grandiose ceremony to rededicate the magnificent Cathedral of Saint-Denis which had been completely rebuild in a revolutionary new architectural style now known as ‘Gothic’. And while being blinded by the dazzling light pouring in from the stained glass windows, decorated with the images of margrave Roland and other heroes of France, she may have dreamed of being buried there, her grave surrounded by the tombs of so many kings and queens of France. However, fate would have something completely different in store for Eleanor.

Funerary mask from the Kitan-Liao (tenth–twelfth century).

The town of Edessa on a postcard from the early twentieth century.

Bernard of Clairvaux blesses King Louis VII of France on his departure for the crusade – engraving by Gustave Doré from the illustrated re-edition of Jean-François Michaud’s History of the Crusades (Paris 1875).

Eleanor of Aquitaine’s effigy on her tomb in the abbey of Fontevraud in Poitou. Although the work is probably near contemporary, the artist made Eleanor look decades younger than she was when she died at age 82.

King Henry II of England deliberating with Thomas Becket, archbishop of Canterbury. Miniature from an early fourteenth-century manuscript of Peter of Langtoft’s Chronicle of England.

Gothic choir of the cathedral of Saint-Denis.

The thirteenth century: the years 1212–1215

1212–1214 were the years of three momentous battles in various parts of Europe, which is in itself remarkable. Battles were usually avoided because of the tremendous consequences they potentially had; not only armies but whole kingdoms could be lost in a few hours. The battles fought in 1212–1214 were all turning points in medieval history: on the field of Las Navas de Tolosa in southern Spain (July 1212) an end was made to the power of the Almohad rulers of al-Andalus, and the Reconquista was decided in favour of the Christians. The battle of Muret (September 1213) put an end to Aragonese ambitions north of the Pyrenees, and opened the road to definitive French royal penetration in the Languedoc. The battle of Bouvines (July 1214) decided the fate of the Angevin Empire of the Plantagenets, who lost all hope of recovering most of their French territories – although the English presence on the battlefield had been limited. The uncontested winner of this outward show of muscle was the French king Philip II August. His Aragonese colleague Peter II, although one of the great heroes of Las Navas, lost his life on the battlefield of Muret as an enemy of Christendom, while the Christian victory over de Almohads at Las Navas brought the king of Castile, Alfonso VIII, to the brink of bankruptcy. Many foreign knights had left his army even before the battle had started because he was no longer able to pay them.

In the same year, 1212, crusading enthusiasm had infected common people for the first time since 1096, and in France and Germany two motley ‘armies’ gathered, mainly consisting of pueri, which must be translated as ‘lads’ rather than ‘children’ – a misapprehension that gave rise to the myth of the ‘Childrens’ Crusade’. Predictably, this youthful enthusiasm led to nothing. The luckier ones returned home after months of hardship; others stayed in the south and settled in the larger cities on the Mediterranean coast (Genoa, Marseilles) which the dwindling armies had managed to reach.

All this did not prevent Pope Innocent III from making yet another urgent call for yet another crusade to the Holy Land. Innocent liked to present himself as the true leader of Europe. In 1215, he convened the Fourth Lateran Council in Rome, the largest church meeting held to date (almost 1,400 church prelates attended the council sessions). It tackled a number of serious problems facing the Roman Church. But Pope Innocent also interfered directly in secular policy; in 1209, he excommunicated John Lackland, King of England, who refused to install the pope’s candidate for the archbishopric of Canterbury. In 1210, the same sanction was meted out to the German King, Otto IV. In the end, Otto had to pay dearly for defying the pope. In 1212, he could not prevent the election of Innocent’s former pupil, Frederick of Hohenstaufen, as (rival) king of Germany. His hopes or turning the tables were dashed at Bouvines, and four years later Otto, disillusioned and ill, was battered to death by a group of priests in Harzburg castle. King John’s reconciliation with the pope came too late to prevent the outbreak of the barons’ revolt, which certainly was not ended with the promulgation of the Magna Carta in June 1215.

In the same year, 1215, a Castilian priest called Dominic Guzman, who by that time was making a career of challenging the so-called Cathar heresy in the Languedoc, had been given several houses in Toulouse for the establishment of a fraternity of preachers, just after the city had been captured by the crusading army that had been set at the Cathars – or rather, at the people of Languedoc. Later in the same year, Dominic travelled to Rome to ask the pope to recognise his friars as a special branch of canons regular, following the rule of Saint Augustine and with the specific task of preaching. The pope yielded after a second visit the following year: the Dominican Order, or Order of Preachers, was born.

One might wonder whether during these exciting events rumours had already reached Europe of the rise of a new and terrible great Khan named Chinggis in the miraculous Far East. In the years 1212–1215 Chinggis was constantly campaigning in the north-eastern part of China. In 1215 he razed the city of Zhongdu to the ground. It was rebuilt as Beijing and would become the seat of government of Chinggis’s grandson, Kublai, who was born in 1215. Kublai became the founder of the Mongol Yuan dynasty and the first Mongol emperor of the whole of China.

The battlefield of Las Navas de Tolosa. Drawing from a Spanish textbook. On the left: the Christian army; on the right, the Muslim army.

Peter II, king of Aragon (1196–1213). Engraving from about 1860 of Peter’s original seal.

Ferrand of Portugal, Count of Flanders, is taken prisoner in the battle of Bouvines. Miniature from a fourteenth-century manuscript of the Chroniques de Saint-Denis.

Children’s Crusade fantasy from a modern children’s book.

Pope Innocent III (Lothar of Segni) (1198–1216), as depicted on a fresco in the Sacro Speco (‘Holy Cave’) at Subiaco, a separate sanctuary close to the Benedictine mother abbey of Sancta Scholastica.

Magna Carta of 1215. Authentic copy in the British Library (Cotton ms Augustus II.106).

Portraits of the Mongol Yuan emperors, starting with Genghis Khan (top left), from a seventeenth-century Chinese manuscript.

The fourteenth century: the years 1321–1324

In September of the year 1321, arguably the greatest poet of the Middle Ages, Dante Alighieri, succumbed to a bout of malarial fever at age 56. Dante’s deathbed was in Ravenna, where he had spent the last years of his life as the guest of the local lord, Guido Novello da Polenta. Dante had been exiled from his native town, Florence, in 1302, after a political coup, and he never returned there. At the time of his death, Dante was still working on ‘Paradise’, the last part of his masterpiece The Divine Comedy; it was probably completed by his eldest son Jacopo, who also wrote the very first commentary on the Comedy.

One of Dante’s other works, On Monarchy (written in Latin) was to be much used, deservedly or not, to defend the position of Louis, duke of Bavaria from the House of Wittelsbach, who had been elected as king of the Romans (king of Germany) in 1314. The election was disputed, and Louis had to tolerate a rival king, his cousin and friend Frederick the Fair of Austria from the House of Habsburg, until the two met on the battlefield of Mühlberg in 1322, where Louis won. This victory paved the road for Louis’ coronation as Roman emperor six years later.

In 1324, far to the south, the inhabitants of Cairo turned out to witness in amazement a stunning procession entering their town. At the centre of allegedly 60,000 soldiers and servants, and 200 camels carrying luggage, was mansa (‘high king’) Musa of Mali, ruler of a desert kingdom larger in size than any principality in late medieval Europe. As a true and faithful Muslim, mansa Musa was making the hajj to Mecca. After his return to Mali he conquered Timbuktu, centre of the gold trade between the West African Guineas and North Africa. He would have been unaware that, while on his way to Arabia, Latin Europe’s most famous traveller, Marco Polo of Venice, had died.

These were all signs that the world was getting larger. But it was quickly changing in another way as well. 1324 saw the publication of Defensor Pacis, an explosive political treatise, whose author, an Italian professor at the Medical Faculty of Paris University called Marsilius of Padua, had wisely, but in vain, tried to remain anonymous. In his book, Marsilius argued that the clergy – including, most importantly, the pope – should not interfere with secular affairs, because that had proved to be a recipe for much trouble in the world; clergy should stick to their business, which was saving souls. Many contemporaries more critical than Marsilius would go even further, and openly declare that in order to acquire God’s grace, the clergy were redundant.

The ugly side of change came to the surface in Ireland, where in 1324 a noblewoman called Alice Kyteler of Kilkenny was accused of sorcery and, in particular, to have had intercourse with the devil. Alice managed to escape, but her unfortunate servant and confidante Petronella was tortured into confession, and then publicly flogged and burned at the stake. It is the first known instance of what would turn into a recurrent pattern of the religious climate in late medieval and early modern Europe: the belief in witches and the witch hunt.

Ironically, the case against Alice Kyteler was initially tried before an inquisition led by a Franciscan bishop who was acting on a recent order of Pope John XXII (1316–1334) to treat sorcery and witchcraft as heresies, while Pope John himself at that time was locked in sordid battle with radical Franciscans, some of whom would end up being burned at the stake as well. In 1323, the same Pope John canonised Thomas Aquinas (†1274), the highly venerated theologian of the rival order of the Dominicans which would become the main supplier of papal inquisitors into matters of heresy during the late Middle Ages.

Dante Alighieri and the Divine Comedy. Fresco by Domenico di Michelino on the west wall of the cathedral of Florence (c.1465).

Battle of Mühldorf, miniature in contemporary manuscript.

Mansa Musa of Mali, ‘lord of the negroes of Guinea’, holding a gold nugget in his hand, as depicted on one of the twelve maps of the so-called Catalan Atlas, made in 1375 by the Jewish Majorcan workshop of Abraham Cresques and commissioned by the French king Charles V – hence its present location, the Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

Kyteler’s Inn in modern Kilkenny (Ireland) still calls to mind the horrible events of 1324.

The so-called ‘Triumph of Saint Thomas Aquinas’, an allegory reflecting the achievements of the Dominican order in science and theology. Fresco by Andrea di Bonaiuto (or: of Florence) in the Spanish Chapel of the Santa Maria Novella complex at Florence (1366–1367).

The fifteenth century: the years 1433–1436

In the year 1433, Jan van Eyck, one of the favourite painters of the Burgundian court of Duke Philip the Good, made a small but beautiful oil painting on wood, now known as the ‘Portrait of a Man in/with a Red Turban’. Modern art historians agree that this is most probably Van Eyck’s self-portrait, and may have been intended as an advertisement for his workshop, to show customers and patrons: ‘Look how realistically I can paint; compare this painted portrait to my real face, and you’ll see no difference!’ The possibility of such a message is confirmed by what is written (in paint) on the painting’s frame: not only is the name of the painter mentioned, as is the exact date on which the painting was completed, it also discloses – in Greek letters – the painter’s personal motto: ‘Als ich can’, which means ‘As I can’ or … ‘As Eyck can’ – which is just one of the puns hidden in these three words. It all testifies to a new self-consciousness, if not self-confidence, that was emerging in works of art and literature of this period, and whose clearest expression in painting was the realistic portrait.

Van Eyck’s portrait does not stand on its own. There are several more paintings from the first half of the fifteenth century containing exactly the same image: a man with a red turban. But none of these compare to Van Eyck’s masterpiece in terms of technical skill in rendering detail and conveying the impression of reality.

One year later, in 1434, when Van Eyck completed the famous ‘Arnolfini Wedding’ – an even more iconic painting for the northern Renaissance – the rich Florentine banker Cosimo de’ Medici returned from exile in his native city and took de facto power over the Florentine city-state. It was the start of the long-lasting Medici regime in Florence and Tuscany. Whereas Cosimo still had to be satisfied with a Circassian slave girl from the Caucasus to mother his bastard son, entirely new possibilities opened in this field with the arrival, that same year, of the first cargo of black slaves on the Lisbon market.

Also in 1434, the Hussite Taborites of Bohemia were defeated by a coalition of Catholics and moderate reformists on the battlefield of Lipany, east of Prague. The battle put an end to the devastating Hussite wars in Bohemia, which had been driven by an explosive mixture of (Czech) nationalism and demands for religious reform.

The year 1435 became the decisive turning point in the Hundred Years War when King Charles VII of France and Duke Philip the Good of Burgundy signed the Treaty of Arras. In exchange for Charles’s promise to give Philip full satisfaction for the murder of his, Philip’s, father, John the Fearless, at Montereau in 1419, Philip in his turn would renounce his alliance with England and recognise Charles as king of France. ‘Arras’ severely diminished English chances of ever winning the war with France, although it would take another 18 years before the last cannon shot was fired.

In 1436 the most impressive architectural tour de force of the Italian Renaissance was consecrated: Filippo Brunelleschi’s ingenious dome of the Santa Maria del Fiore – the cathedral of Florence. It had taken Brunelleschi 25 years to complete his masterpiece.

Archival sources from the city of Strasbourg from the years 1434–1436 are the first to mention the name of an immigrant goldsmith, Johannes Gutenberg. Three years later Gutenberg would start his revolutionary experiments with moveable type printing that would change the world for good. It would take another 15 years before Gutenberg, by then living in Mainz, printed his first major book, which of course was the bible. 48 copies of this first printed edition are still in existence.

Jan van Eyck’s ‘Portrait of a Man with a Red Turban’. National Gallery, London. Posthumous portrait of Cosimo de’Medici by Jacopo da Pontormo, 1519–1520. Modern memorial at the battlefield of Lipany, Czech Republic. Charles VII, king of France (1422–1461). Contemporary portrait by Jean Fouquet, c.1445, now in the Louvre Museum, Paris. The cathedral of Florence with Brunelleschi’s dome. Model of Brunelleschi’s dome. Library of Congress copy of the Gutenberg bible of c.1454.

Fictionalising the Middle Ages in movies and novels

The typical artistic expression of contemporary medievalism is the fictionalisation of the Middle Ages in movies and television series, novels, fantasies, opera, architecture and decorative arts, painting and sculpture, comics, computer games, and re-enactment play. Studying these diverse genres of both highbrow and pop(ular) culture is a specialist, interdisciplinary field in itself, supported by its own publication media, such as Studies in Medievalism.

The limited purpose of this website is to present a selection of movies and novels on the Middle Ages that may enrich students’ understanding of the medieval period by underscoring the difference between the picture emerging from summarising scholarly research (the chapters in the book) and the far more distorted images that emerge from fictionalised re-creations of the Middle Ages (the movies and novels on the list). The latter have the advantage on the former that in movies and novels all kinds of facets of past life that historians have to put aside – how people in the distant past, and known historical persons in particular, spoke and behaved – are filled in. Its downside is that historical fiction is not always based on adequate scholarly knowledge or else is wilfully adapted to modern taste in order to answer the expectations of viewers and readers. This leads to an image of the medieval world that is distorted in two directions: the grotesque and the romantic. The former refers to the stereotypical dark side of the medieval image, including lots of violence, bloodshed and witchcraft, while the latter is characterised, in the words of David Matthews, by ‘stereotyped gender roles (with many damsels in distress), fear of technology, and dreams of powerful monarchies’ (Medievalism: A Critical History, 29).

To create a balanced and representative overview of even just movies and novels that are situated in the Middle Ages would be a task far beyond our reach. A survey of ‘medieval historical novels in the English language’ by Shuan Tyas counted more than 5,000 items (Proceedings of the Harlaxton Symposium 2005), and the number of ‘films set in the Middle Ages’ also runs in the hundreds, witness various lists on websites such as IMDb (International Movie Database) and Taste of Cinema. Students whose interest extend beyond what follows can start their own research on such rich specialist websites as medievalists.net and medievalnews.blogspot.com.

Our two shortlists are selections based on what we happened to read and watch over the last decades, with varying degrees of admiration, amazement and dismay.

A. Movies on the Middle Ages

| Chapter of book | Title, year and director of movie | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | King Arthur: Legend of the Sword (Guy Ritchie, 2017) | The latest of countless movies on the legendary hero of ‘Dark Age’ post-Roman Britain. |

| 2 | Agora (Alejandro Amenábar, 2009) | Over-emotional picture of Christian violence against ‘pagans’ in late-Roman Alexandria, starring Rachel Weisz as the female philosopher Hypatia. |

| 2 | The Virgin Spring (Ingmar Bergman, 1960) | The second movie on medieval Scandinavia by the famous Swedish director opposes a cultured Christian lady, who is raped, to a ‘wild’ pagan servant girl, who is pregnant. Won Bergman his first Oscar. |

| 3 | The thirteenth Warrior (John McTiernan, 1999) | Vikings meet Slavs. Clever mixture of Beowulf and Ibn Fadhlan’s travel account. But Spanish actor Antonio Banderas is miscast. |

| 3 | Severed Ways: The Norse Discovery of America (Tony Stone, 2007) | Story, set in 1007, of two Icelandic Vikings who get lost in the North American forests. One finds religious comfort through an Irish monk (the true Columbus?), the other sexual relief in the arms of an Indian woman. A recipe for disaster. |

| 4 | The Lion in Winter (Anthony Harvey, 1968); The Lion in Winter, miniseries (Andrej Konchalovsky, 2003) | Two screen versions of the play by James Goldman on the Angevin family. Compare Katherine Hepburn with Glenn Close as Eleanor of Aquitaine, and Peter O’Toole with Patrick Stewart as Henry II! |

| 4 | Ironclad (Jonathan English, 2011) | Improbable story on John Lackland’s siege of Rochester in 1215 stars Paul Giamatti as an interesting version of King John. |

| 4 | Becket (Peter Glenville, 1964) | This older, theatrical movie on another main character of Angevin England, Thomas Becket, has a remarkable cast, with Richard Burton, Peter O’Toole and John Gielgud. After the play of the same name by Jean Anouilh. |

| 5 | Marketa Lazarová (Frantisek Vlácil, 1967) | Generally considered to be one of the best cinematic representations of the medieval world ever made. Staged in rural Bohemia in the thirteenth century; haunting and complex. Only to be compared with Tarkovsky’s Rublev (next item). |

| 5 | Andrei Rublev (Andrej Tarkovsky, 1966) | Made in about the same period of Soviet domination as Marketa Lazarová. Equally haunting image of grim medieval world, to which only an icon painter can add bright colour. |

| 5 | La passion Béatrice (Bertrand Tavernier, 1987). | Forget about a cosy life in luxury on a medieval castle. Staged in France in the middle of the fourteenth century, this movie pictures the extreme violence of the medieval nobility in a household setting. A story about sin for which no redemption can be found. Fabulous role by Bernard-Perre Donnadieu as castle lord. |

| 5 | Robin Hood (Ridley Scott, 2010) | Second excursion to the Middle Ages by one of the world’s leading action movie directors. Not everybody will be taken in by Russell Crowe’s casting as main character, but the script is interesting because it attempts to provide the legendary Robin Hood with a credible historical background. |

| 6 | Francesco giullare di Dio (Roberto Rossellini, 1950); Brother Son, Sister Moon (Franco Zeffirelli, 1972) | Two famous Italian directors from the second half of the twentieth century ventured to make a movie on arguably the most appealing medieval saint: Francis of Assisi. Unsurprisingly, Rossellini’s is more realistic, Zeffirelli’s more romantic. |

| 6 | Vision – From the Life of Hildegard von Bingen (Margarethe von Trotta, 2009) | Attempt to bring into being the twelfth-century multitalented abbess Hildegard von Bingen by feminist director Von Trotta. |

| 7 | Kingdom of Heaven (Ridley Scott, 2005) | Latest crusader blockbuster, which after a gripping start gradually falls back to an average Hollywood mass spectacle. One of the first movies on the crusades, though, in which not all the crusaders are good guys and not all the Muslims are bad guys. In that sense, this movie tells more about what was going on in 2005 than in the twelfth century. |

| 7 | Mongol (Sergey Bodrov, 2007) | Powerful representation of the rise to power of Temüjin/Chinggis khan, based on the contemporary Secret History of the Mongols, which combines historical facts with myths. Amazing acting by the Mongol boy who plays young Temüjin. |

| 7 | Valhalla Rising (Nicolas Winding Refn, 2009) | Band of Viking merchants/crusaders(?), in search of heaven, finds nothing but hell, thanks to the company of a one-eyed human devil who himself meets death at the hands of Indians in accidentally discovered America. Not for the weak-hearted among us. Extremely violent and disturbing. |

| 8 | Stealing Heaven (Clive Donner, 1988) | Medieval philosophy and theology does not make good theatre, but here’s one movie on Peter Abelard, played by Dutch actor Derek de Lint, with Kim Thomson from Scotland as Heloise. |

| 9 | Il Decameron (Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1971) | Medieval towns are often enough the setting of movies on the Middle Ages, but urban life and urban politics rarely dominate the plot. If we consider Giovanni Boccaccio as a typical exponent of Italian urban culture of the fourteenth century, then his masterpiece Decamerone could be seen as a typical product of that culture. |

| 10 | The Seventh Seal (Ingmar Bergman, 1958) | To play chess with Death was one of the allegories for death-struggle often used in fourteenth-century Europe. Turned by Bergman into Leitmotiv of odyssey made by knight returned from Holy Land through death-ridden Denmark. |

| 10 | The Navigator (Vincent Ward, 1988) | Intriguing story of a small village in northern England that is hit by Black Death. Viewers who want to give up when the plot becomes incredible should persist. The (Christological) end is truly original, convincing and haunting. It will knock many of their chairs. If medieval religious mentality has ever been approached in a modern movie, it is in The Navigator. |

| 10 | Black Death (Cristopher Smith, 2010) | The Navigator’s counterpart: Savage and sadistic movie that brings back the stereotypical image of Middle Ages as dark and violent period with all the clichés (pagan magic, witch hunting) that make part of it. |

| 10 | The Reckoning (Paul McGuigan, 2003) | Not very well-received movie based on Barry Unsworth’s acclaimed novel Morality Play (see historical novels on Middle Ages). |

| 11 | Alexander Nevsky (Sergei Eisenstein, 1938) | Stalinist representation of historical Russian-German trial of strength that curbed the territorial ambitions of the Teutonic Order in the thirteenth century. |

| 11 | Braveheart (Mel Gibson, 1995) | This over-romanticised biopic of the Scottish hero William Wallace made of its Australian acting director (or directing actor) an unlikely symbol of renewed Scottish nationalism. |

| 11 | The Messenger: The Story of Joan of Arc (Luc Besson, 1999); Jeanne captive (Philippe Ramos, 2011) | Latest two in a long tradition of Joan of Arc movies that goes back to the early cinema. It produced several master pieces – that of Carl Theodor Dreyer of 1928, to start with – which these two are not. We also bet that Besson’s then wife Milla Jovovich does not look like the historical Joan. |

| 12 | The Name of the Rose (Jean-Jacques Annaud, 1986) | Successful adaptation of the equally successful novel by Umberto Eco, with Sean Connery in the unlikely role of a Franciscan Sherlock who reveals himself as a mixture between Roger Bacon and William of Ockham. |

B. Major television series of the last few decades related to historical events and/or persons in the Middle Ages

- Cadfael [based on mystery novels by Ellis Peters]

(various directors, 1994–98) - Joan of Arc (Christian Duguay, 1999)

- Attila (Dick Lowry, 2001)

- Robin Hood (various directors, 2006–09)

- Pillars of the Earth (Sergio Mimica-Gezzan, 2010)

- World Without End (Michael Caton-Jones, 2012)

- The Borgias (various directors, 2011–13)

- Vikings (various directors, 2013–)

- The White Queen (various directors, 2013)

- Marco Polo (various directors, 2014–)

- The Last Kingdom (various directors, 2015–)

- The White Princess (various directors, 2017)

Acclaimed literary novels on the Middle Ages (20th–21st centuries)

| Author | Title and year of first publication | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Sigrid Undset | Kristin Lavransdattar, trilogy (1920–22); two volumes have been translated into English | The main character is the unconventional daughter of a Norwegian nobleman living in the fourteenth century. Is all about sin and remorse. |

| Sigrid Undset | Olav Audunssøn (Eng. The Master of Hestviken), 4 vols (1925–27) | Not really a sequel but loosely related to the Kristin trilogy, and set in the same period of time. Undset is particularly praised for her complex character development and the convincing historicity of her narrative. Her medieval novels won Undset the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1928. |

| William Golding | The Spire (1964) | Another winner of Nobel Prize for Literature. The Spire is a story of hubris connected to building of a cathedral in twelfth-century England. |

| Daphne du Maurier | The House on the Strand (1969) | A hallucinogenic drug developed by a scientist friend sends publisher Dick Young 600 years back in time, where he meets his medieval alter ego, falls in love, and experiences the disasters of the mid-fourteenth century in Cornwall. |

| Michael Crichton | Timeline (1999) | Another time-travelling novel that hurls twentieth-century people back into the post-plague period, this time through a quantum wormhole that links Arizona with Languedoc. Again, love for a woman is the transcending force that makes life in the Middle Ages acceptable, at least for one time traveller. Curious mixture of Du Maurier’s novel and Crichton’s own mega-bestseller, Jurassic Park. |

| Barry Unsworth | Morality Play (1995) | Moving story, set at the end of the fourteenth century, of a renegade cleric who joins a troupe of travelling players and then gets embroiled in a murder case. Shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize, won by Unsworth three years earlier. In 2003 the book was turned into a film entitled The Reckoning (see movies). |

| Barry Unsworth | The Ruby in Her Navel (2006) | Romantic story set in twelfth-century Norman Sicily. Again shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize. |

| Matt Cohen | The Spanish Doctor (1984) | Story of the fate of the Iberian Jews and of their renewed diaspora in the century after the Black Death, told as the fictive biography of a Jewish physician, who was born in Spain, lived in southern France, and died in Russian Kiev. |

| Umberto Eco | Il nome della rosa (1980; Eng. The Name of the Rose) | Clever whodunit set in the beginning of the fourteenth century against background of the poverty controversy between pope and Franciscan order. The novel’s almost scholastic construction has an intriguingly metatextual complexity. |

| John Fuller | Flying to Nowhere (1983) | Often compared to Eco’s Name of the Rose. Mystery story about pilgrims who have disappeared near a sacred well, again with medieval monks (this time Welsh monks) as main characters. Admirers praised its poetic language, critics its vagueness. At the time nominated for the Man Booker prize. |

| Umberto Eco | Baudolino (2000) | Brings medieval East and West together in story centred on meeting between upstart Lombard peasant boy promoted to knight and Byzantine historian Niketas Choniates, set in time of the fourth crusade. |

| Malcolm Bosse | Captives of Time (1987) | Orphaned brother and sister travel through plague – and war-ridden England at the end of the fourteenth century. A central concern is the capture of time by a new invention: the clock. |

| Adam Thorpe | Hodd (2009) | Literary counterpart of Ridley Scott’s Robin Hood movie of about the same time. Complex, layered historical novel attempts to demythologise the Robin Hood story by making robber Hodd the main character of a medieval manuscript discovered and published by an amateur scholar in France shortly after World War I. Readers had mixed appreciations. |

| Iain Pears | The Dream of Scipio (2002) | Reflection on the madness of times in a complex novel that interconnects three historical periods of ‘barbarism’ in the same geographical space (Provence): the post-Roman world of the barbarian Invasions, the fourteenth century, and the years of World War II. Certainly not as good a read as An Instance of the Fingerpost by the same author, but that novel is set in the seventeenth century. |

| Ken Follett | The Pillars of the Earth (1989) | First of two excursions to the medieval period by Welsh best-seller author (a third part has been announced). Both are set in the (fictive) late medieval small town of Kingsbridge; on the building of a cathedral. Pillars sold 18 million copies. |

| Ken Follett | World Without End (2007) | Sequel of Pillars, focused on the disasters of the fourteenth century (plague, war). Both novels were made into successful television series. |

Click image to expand

0.1 The oldest known independent map of Europe, drawn around 1121 by Lambert, canon in Saint-Omer, in his richly illustrated encyclopaedia Liber Floridus. Europe is seen as a quarter of the world. According to classical, Mappa Mundi representation the upper half of the inhabited world was taken in by Asia; the fourth quarter by the third continent, Africa. The Danube, the Rhine and the Rhône can be distinguished, as well as the Alps and the Pyrenees as boundaries to the Italian and Iberian peninsulas; Rome is marked with a cross on a major building. Empirical data are ordered within an overall idealistic world view, from the Huns and Germanic peoples top left, to Greece, Germany and Gaul, all with their regions.

1.2 ‘All roads lead to Rome’. Detail from the Peutinger Table, a copy of a third-century Roman map of roads and watercourses, named after the humanist Conrad Peutinger. Towns and rivers are particularly recognisable.

1.3 Rural scenes around a North African villa, c.400, depicted on the so-called Seigneur Julius mosaic.

1.4 In the late Empire and the early Middle Ages, Roman cities lost their function and shrank to small dimensions. This implied a shift of the dwellers’ cultural preferences and the magnificent ancient buildings fell into ruin. Typically, the arena in Arles became filled with medieval houses, as shown in this woodcut from the sixteenth century.

2.1 The winged symbols of the Four Evangelists mark the introductory page to the Gospel of St Matthew in the Book of Kells. This is the most brilliantly illuminated Celtic manuscript, created in around 800 in the abbey of Iona (western Scotland) and in the Irish Kells, to which monastery the monks had fled from Viking raids. Ten of its 340 folios are full-page pictures in vibrant colours, combining Christian iconography with swirling motifs and interlacing patterns in the insular tradition. These recur in the interlinear ornamentation and the decorated initials. In addition to the Latin texts of the four Gospels, the manuscript contains tables of concordances between the Gospels and summaries of their narratives. The book illustrates the riches of Irish monastic life.

2.2 Miniature painting depicting the two cities, in a manuscript of Augustine’s The City of God, in a French translation, composed in Paris c.1475–1480. On top, God and Mary sit enthroned in the heavenly city that is walled; they are surrounded by saints, and seven saintly ladies are guiding as many exemplary men towards the gate. The earthly city is also walled, and around it seven devils are dancing, representing the capital sins. The latter are divided in seven city wards, each with their virtuous opposite. From the top right clockwise: voluptuousness, gluttony, greed, laziness, quarrelling, jealousy and pride.

3.1 Ritual of ‘joining hands’ with the king (immixtio manuum in Latin), the symbolic sealing of a contract with a vassal. The Royal Prosecutor, the Scribe and the Feudal Lord. Capbreu de Clayra et de Millas, 1292, Catalan School.

3.2 The hull of the burial ship found at Öseberg near Oslo, Norway, had ceremonial purposes, but is also a fine example of the large boats with which Vikings carried out their raids over the seas.

4.1 Silvester, bishop of Rome from 314 to 331 and the first called pope, baptises Emperor Constantine. This is one of eleven mural paintings dated 1248 in the church of the Quattro Santi Coronati (Four Crowned Saints) in Rome. They illustrate the legend by which Constantine was healed of leprosy thanks to Silvester’s invocation of St Peter and St Paul and then baptised. This iconographic programme fitted into Pope Innocent IV’s propaganda against Frederick II, claiming superiority of the Church over the emperor.

4.2 Harold, earl of Wessex, swears his oath on holy relics as the successor to King Edward the Confessor, 1066. The tapestry preserved in Bayeux, Normandy, is a uniquely realistic depiction in fifty scenes of the power struggle ending in the Battle of Hastings. The embroidery on cloth is nearly 70 metres (230 feet) long. It was made shortly after the events and the colours are wonderfully preserved. The central scene has titles in Latin, and strips at the top and bottom show animals and drolleries as well as highly precise images such as the oldest representation of the mouldboard-plough.

4.4 The castle of Montsó, constructed by the Muslim rulers, conquered by the count of Barcelona in the middle of the twelfth century, was strategically located on the border between Catalonia and Aragon. The Military Order of the Temple exploited it as one of its principal ‘commanderies’. Tenth century.

5.1 Difficult relations between landlords and peasants are exemplified in the enamel decoration of a small portable altar in gilded copper created around 1160 in the middle Meuse region. The images are surrounded by quotes from Matthew 21:33–42, which are illustrated in four plaques 4.9 cm high, the larger ones 22 cm long, and two shorter ones 11.8 cm long. The iconography reveals inspiration from the tenth-century Codex Aureus from the abbey of Echternach (Luxemburg). The story tells of an absentee landowner who had a vineyard planted, and a winepress and a tower constructed. He leased his property to vinedressers. When he twice sent some of his servants and finally his son to collect the harvest, they were beaten, stoned and killed by the vinedressers, who saw an opportunity to seize the inheritance.

5.2 Girding on a knight’s sword. Chansons de Guillaume d’Orange, first half of the fourteenth century.

6.1 The imposing buildings of the abbey of Cluny, destroyed during the French Revolution, after a lithograph by Émile Sagot, after 1798.

6.2 The abbey of Fontenay in north Burgundy is a fine example of Cistercian principles: located at the fringes of civilisation, it was built in a sober style, contrasting with the luxury of the older Benedictine abbeys, and there was a clear involvement in agricultural and technical innovations. The location was chosen in 1118 by Bernard of Clairvaux in a valley amply provided with running water, which was used to supply energy to watermills which powered bellows and hammers in the forge. In this 53-metre-long twelfth-century building, iron-ore mined nearby was worked into metal tools.

6.3 St Francis supports the Church, which has collapsed. Allegorical fresco by Giotto (c.1267–1337) in the upper church of the basilica of St Francis at Assisi.

7.2 The crusaders’ fortress Krak des Chevaliers was raised in the County of Tripoli, Syria, after the First Crusade. It could house 2,000 soldiers.

7.3 The silk routes connecting China with the western trading posts in the Near East passed through the south Asian deserts where only camels could endure the hard conditions. During the Tang dynasty (618–907), trading relations intensified. Earthenware from that period represents various types of travellers.

7.4 The drapery market at Bologna in the fifteenth century, as represented in the drapers’ guild register.

8.1 Hereford mappa mundi, depicting the three inhabited continents, with Jerusalem in the centre, directly below the Tower of Babel and the Garden of Eden.

8.2 The ‘three philosophies’ (natural, rational, moral) reign as a three-headed queen over the seven liberal arts. Gregor Reisch, Margarita Philosophica (Freiburg 1508).

9.1 Ypres was a large centre of textile production and one of the cities where international fairs had been held since well before their first mention in 1127. At the height of its development, the local government decided to construct a worthy drapers’ hall to facilitate the trade. Works started in 1260 and in 1304 the largest civic building of the Middle Ages was finished. Its façade was 133 metres long and its surfaces totalled 5,000 square metres. The heavy belfry tower was 70 metres high. Originally, a belfry was a symbol of seigneurial power, but the cities of Flanders and Hainaut adopted this model as a watchtower where bells signalled alarm as well as working hours. The building was nearly destroyed by the bombardment in November 1914, but entirely reconstructed after the war.

9.2 Republican theories of power emanating from the citizenry were formulated in Tuscany both in treatises and in monuments. In the town hall of the autonomous city of Siena, with its impressive 120-metre high tower, the meeting room of the Council of Nine Governors (Signori), elected from the merchants’ oligarchy, was decorated with frescoes by Ambrogio Lorenzetti, painted between 1337 and 1340. They illustrate the city’s good government, based on the constitution and the commune’s desire for peace, concord and justice. This idealistic view of a city shows various artisans at work in their shops, in construction and transport.

9.3 The relatively small Tuscan town of San Gimignano still features a number of impressive medieval towers belonging to the fortified houses of the patrician families. Originally they expressed the pride of the dominant families, and in times of conflict they served a military purpose. Most of these towers here and in other towns collapsed over the centuries or were torn down by order of the local authorities.

9.4 Venice was the largest and wealthiest medieval metropolis, heading a huge maritime empire. The cathedral, the bell tower and the palace of the doge are in the centre of the image; the arsenal and shipyard is a walled area with docks on the extreme right.

10.1 From cardinal to minstrel, everybody is dragged into death by skeletons. The theme of the danse macabre became popular after the recurrent outbreaks of the plague. Early fifteenth-century mural painting in the church of La Ferté-Loupière (France, Dep. Yonne).

10.3 Distribution of bread to the poor, one of the panels representing the Seven Works of Charity commissioned in 1504 by the confraternity of the Holy Ghost in Alkmaar (North Holland). Various religious institutions distributed food and other necessities to poor people, whose numbers might grow in years of bad harvests to one-quarter of the population.

11.1 James I, count of Barcelona and king of Aragon (1213–1276), sitting on his throne with the sword of justice upright, accompanied by two councillors and a soldier, oversees the justice rendered by a seated judge in a dialogue with two advocates holding written documents, and their female and male clients. Vidal Mayor, Book of the Deeds, late thirteenth century.

11.2 Ceremonial session of the two Houses of Parliament in 1523. This highly ceremonial representation shows the king on his throne with three ecclesiastical councillors to his right and two laymen to his left. The seating order in quadrangles reflects this division: lords spiritual are seated on the king’s right and lords secular in front and on the left. In the centre, officials are seated on four woolsacks and there are two scribes. The herald appears to allow the Commons to take their places.

12.1 Pope Boniface VIII, statue in copper and bronze on wood, 2.45 m high, c.1300 on show on the façade of the Palazzo Pubblico of Bologna.

12.2 The Seven Sacraments. This magnificent altarpiece by Rogier van der Weyden was commissioned between 1440 and 1445 by Jean Chevrot, bishop of Tournai and head of Duke Philip of Burgundy’s Great Council. The triptych is framed as a church interior with the main sacrament, the Eucharist, in the nave, and the six others in the aisles, following the human life-cycle from left to right: baptism, confirmation, confession, ordination of a priest, marriage and anointing of the sick.

12.3 The Well of Life symbolises the Church, topped by God the Father, Mary and the Crucified Christ. The mystic winepress demonstrates how the blood of Christ’s suffering is offered in the Eucharist by angels to the believers. These are represented here in the traditional hierarchy of the clergy in the forefront, the aristocracy led by the emperor, the third estate, and pilgrims. The original frame, decorated with the Arma Christi, the Instruments of the Passion, signifies that this painting served as the epitaph of a cleric from the northern Low Countries who died in 1511 and had himself portrayed kneeling with a chalice.

12.4 Episodes from the lives of hermits are shown in this rather enigmatic painting by Fra Angelico, which he named ‘Tebaide’, after the Egyptian city of Thebes. There, in the desert, St Pacome (296–346) founded the first Christian monastery with a rule. Angelico found his inspiration in anthologies of the lives of saints from the fourth to the tenth centuries, and in the Golden Legend by James of Varazze. Miracles performed by hermits and their encounters with devils are shown in a strange composition, possibly as a motivation for the new wave of eremitism at the time of the painting, around 1420.

12.5 Purgatory: angels rescue the souls of women who have fulfilled their penance and will be elevated to heaven. Note the head with a prelate’s mitre and a couple of shaved monks’ heads among those having to continue their penance. Miniature in the Très riches heures du duc de Berry (the illuminated Book of Hours), early fifteenth century.

Click image to expand

Click image to expand

Figure 3.1 1 Non-commercial transactions in the early Middle Ages through reciprocity (1) and redistribution (2).

Figure 4.1 Family tree of the emperors and kings of the (German) Roman Empire, showing changes in dynasties during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.

Links to useful websites

Like any other topic of interest, the Middle Ages are all over the internet. Thanks to advanced search machines such as Google, most treasures that float around are relatively easy to find. Entries on any subject or aspect of medieval history on open access sources such as Wikipedia, in addition to offering (usually) useful introductory information, have links to relevant literature and specialised websites, while YouTube offers free lectures on general medieval history by some of the world’s leading specialists in the field.

In addition, there are some convenient sites for doing (medieval) historical research whose main function is to point to other, more specialised sites. Examples are the ‘about.com’ entry on medieval and Renaissance history http://historymedren.about.com, the online research library www.questia.com (access for subscribers only), www.medievalists.net, NetSERf: The Internet Connection for Medieval Resources (Catholic University of America): www.netSERF.org, the Online Reference Book for Medieval Studies www.the-orb.net, New York University’s site Medieval and Renaissance Studies: A Guide to Research: http://nyu.libguides.com/medieval, and www.besthistorysites.net/index.php/medieval-history.

For secondary school teachers, the ACT History Teachers’ Association has developed http://cliojournal.wikispaces.com, which offers interesting discussion of focused subjects of Late Antique and medieval history – for ancient history there is also the Ancient History Encyclopedia at www.ancient.eu.com.

The best digital bibliographies for medieval history are:

- The International Medieval Bibliography (IMB), produced by an editorial team at the Medieval History Department of the University of Leeds, and hosted by the Belgian publisher Brepols. The IMB is only accessible for subscribers through the portal www.brepolis.net, which gives also access to the Bibliography of British and Irish History and the encyclopedia Lexicon des Mittelalters (in German) and its supplement International Encyclopedia for the Middle Ages – online (in English).

- The free-access Literatursuche (‘Literature Search’) or RI-Opac facility of the Regesta Imperii project of the Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Literatur at Mainz: www.regesta-imperii.de (the site is in German, but for the literature research one can switch to English).