Professionals

Welcome to the Professionals’ section of the Growing Up with Two Languages website. Here you will find information, resources, and advice for professionals (teachers, midwives, doctors, and so on) working with families who speak a minority language at home.

The links here will take you to information pages where you will find links and resources for further reading, and to relevant stories from people talking about their experiences and/or thoughts on the fact that they speak a minority language at home. The stories were collected in interviews carried out for the ‘bilingual teens’ ITML project. You may also find information in the Parents and Children sections helpful.

If you are a teacher working with multilingual students and their families, take a look at the resources for enhancing the linguistic landscape of your setting. Please see also the chapter for teachers in Growing Up with Two Languages. There is a chapter for healthcare professionals too.

If you want to get in touch, please contact us via our Facebook page. We’d love to hear from you!

Professionals intro

Myths about bilingualism

Some teachers see children who come from elsewhere as a problem. And I think: “Those teachers have not quite kept up with new developments!” But when parents get feedback like this from the class teacher they no longer know what to do. They will believe the teacher and try to speak English at home, so then you get broken English as the home language. So the children lose their heritage language but don’t get good English either. It’s very sad.

Dutch mother and ESOL teacher, living in Christchurch

Historically, throughout much of the world, deliberate attempts have been made to create monolingual societies by eliminating minority languages. It was commonly thought that speaking a single, majority language could bring many benefits to the citizens of a country such as by facilitating education on a national scale, for example, or creating unified systems for national administration. New Zealand followed a similar pattern of minority language suppression as many other countries worldwide when speaking Te Reo Māori in school was officially prohibited in the late 1800s.

It was also around this time that early research into bilingualism began to emerge. However, since international focus was on the benefits of monolingualism it is not surprising to note that research findings were consistently negative towards bilingualism (see the quote above, for example). Unfortunately, myths that speaking more than one language leads to linguistic confusion, impedes intellectual development or negatively affects academic performance still persist today despite all of these claims having been repeatedly and comprehensively discredited since around the 1930s.

Every bilingual situation is different, and there are therefore many ways to be bilingual. People who speak more than one language tend to know each language only to the level that they need to use it, which means they may find one language more dominant or have a richer vocabulary in one language for discussing certain topics. This is normal and is not a sign of impeded intellectual development, in much the same way that the mixing of languages (also known as code-switching) is normal, and is not a sign of linguistic confusion. Furthermore, countless studies have shown that bilingualism often in fact has positive – rather than negative – effects on academic achievement.

Perhaps because it has been surrounded by such negativity in the past, bilingualism is something about which people tend to feel very strongly. Strong opinions about the perceived ‘value’ of certain languages over others are not uncommon either, and it may reassure a bilingual family to know that they are not alone if they regularly receive comments, opinions, and advice from strangers about the language(s) they use. Learning any language is enriching in many ways, however, and parents raising their children with one (or more) minority language(s) should feel assured that they are doing a good thing even if their journey is not always straightforward.

See Growing Up with Two Languages for more information.

Helpful links on bilingual myths

- Myths about bilingualism– written by François Grosjean, Professor Emeritus of the Université de Neuchâtel and founder of the academic journal Bilingualism: Language and Cognition.

- Common myths about bilingualism – written by the University of Hawai’i Centre for Second Language Research.

- Myths about bilingualism – written by Shirley Maihi, Principal of Finlayson Park School and creator of the Bilingual Education New Zealand website.

- Raising bilingual children: Fact or fiction? – written by Christina Bosemark, founder of the Multilingual Children’s Association.

- Debunking common myths about raising bilingual children – easy to read article from Australian publication The Conversation.

- TEDx Talk on reducing monolingualism in the United States– (with some interesting points applicable in New Zealand) by Kim Potowski, Associate Professor of Linguistics at the University of Illinois.

- The politics of bilingualism – the story of a boy suspended for speaking Spanish at school.

- Bilingual kids in the classroom a treasure – opinion article from the NZ Herald.

Multilingualism and development, disorders and interventions

- Texts on raising and working with bilingual children – written by Dr Susan Dopke, speech pathologist and consultant in bilingualism.

- If a multilingual child does have a disorder, switching to monolingualism will simply create a monolingual child with a disorder. It will not address the disorder itself –article about recommending monolingualism for children with speech disorders, written by multilingual parent, educator and scholar Madalena Cruz-Ferreira, University of Manchester.

- Recommending monolingualism to multilinguals: why and why not – written by multilingual parent, educator and scholar Madalena Cruz-Ferreira, University of Manchester.

- What to do when a bilingual child has been diagnosed with a language disorder – written by Professor François Grosjean.

Additional resources on bilingual myths

Baker, C., & Hornberger, N. (2001). The influence of bilingualism on cognitive growth: A synthesis of research findings and explanatory hypotheses. In An introductory reader to the writings of Jim Cummins (pp. 26–55). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Cruz-Ferreira, M. (2010). Multilinguals are…? London/Colombo: Battlebridge Publications

Grosjean, F. (2010). Effects of bilingualism on children. In Bilingual: Life and reality (pp. 219–228). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Hakuta, K., & Diaz, R. (1985). The relationship between degree of bilingualism and cognitive ability: A critical discussion and some new longitudinal data. In K. Nelson (ed.), Children’s language (Vol. 5, pp. 319–344). Hillside, NJ: L. Erlbaum.

Pavlenko, A. (2014). The turn in the study of language and cognition. In The bilingual mind and what it tells us about language and thought (pp. 18–39). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Peal, E., & Lambert, W. (1962). The relation of bilingualism to intelligence. Psychological Monographs,76, 546.

Valdes, G., & Figueroa, R. (1994). Bilingualism and testing: A special case of bias. Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing Corporation.

TEDx talk on the ‘monolingual mindset’ and how to better incorporate minority languages in teaching and learning – by Felicity Meakins, research fellow at the University of Queensland and field linguist specialising in Australian Indigenous languages.

Advantages of bilingualism

One language sets you in a corridor for life. Two languages open every door along the way

Frank Smith, Psycholinguist, in his book To think, 1990

At the most basic level, being raised with more than one language from birth is beneficial for children in that it opens up future travel, educational, literary, employment and marriage opportunities. In addition to this – and contrary to any negative myths about bilingualism that may still persist today – countless studies have shown that bilingualism also has positive and lasting effects on brain function and memory (see, for example, Bialystok et al, 2012; Craik et al., 2010; Kovács and Mehler, 2009; Luk et al., 2011; Mohades et al., 2015).

Children being raised bilingually from birth learn their languages slightly differently than monolingual children; however, there is little evidence to suggest that this causes language developmental delay (De Houwer, 1999; Petitto and Holowka, 2002). Zurer Pearson (2008) discusses a number of studies looking at language development milestone measures, and suggests that individual differences between children have more of an influence on language development than the number of languages a child is learning. Bilingualism may be wrongly blamed for speech delay in a child who in fact has another underlying disorder or, in some cases, the term ‘delay’ may mistakenly be used in a context where the problem is in fact unintelligibility. This is a surprisingly common occurrence whereby a child’s early vocalisation is not recognized as ‘real’ speech by parents/carers who are not listening for the right language (Navarro, 1998).

Bjork and Kroll (2015) argue that the extra work bilingual children have to do when learning more than one language is in fact beneficial for their brain development, and that this could, in turn, explain the plethora of cognitive advantages associated with bilingualism. A number of recent studies have shown significant differences between simultaneous bilinguals (individuals who learn two languages from birth) and those who acquire a second language later on (Kaiser et al., 2015; Krizman et al., 2015), confirming the idea that exposure to more than one language is beneficial right from day one.

For more information, see Growing Up with Two Languages.

References

Bialystok, E., Craik, F. I., & Luk, G. (2012). Bilingualism: Consequences for mind and brain. Trends in Cognitive Science, 16(4), 240–250.

Bjork, R. A., & Kroll, J. F. (2015). Desirable difficulties in vocabulary learning. American Journal of Psychology, 128(2), 241–252.

Craik, F., Bialystok, E., & Freedman, M. (2010). Delaying the onset of Alzheimer disease: Bilingualism as a form of cognitive reserve. Neurology, 75, 1726–1729.

Cunningham, U. (2011). Research and further reading. In Growing up with two languages (3rd ed., pp. 164–184). London and New York: Routledge.

De Houwer, A. (1999). Two or more languages in early childhood: Some general points and practical recommendations. Washington, DC: Center for Applied Linguistics.

Kaiser, A., Eppenberger, L., Smieskova, R., Borgwardt, S., Kuenzli, E., Radue, E.-W., Nitsch, C., & Bendfeldt, K. (2015). Age of second language acquisition in multilinguals has an impact on gray matter volume in language-associated brain areas. Frontiers in Psychology, 8(6).

King, K., & Fogle, L. (2006). Raising bilingual children: Common parental concerns and current research. CAL Digest.

Kovács, Á., & Mehler, J. (2009). Cognitive gains in 7-month-old bilingual infants. PNAS, 106(16), 6556–6560.

Krizman, J., Slater, J., Skoe, E., Marian, V., & Kraus, N. (2015). Neural processing of speech in children is influenced by extent of bilingual experience. Neuroscience Letters, 585, 48–53.

Luk, G., Bialystok, E., Craik, F. I. M., & Grady, C. L. (2011). Lifelong bilingualism maintains white matter integrity in older adults. The Journal of Neuroscience, 31(46), 16808–16813.

Mohades, S., Van Schuerbeek, P., Rosseel, Y., Van De Craen, P., Luypaert, R., & Baeken, C. (2015). White-matter development is different in bilingual and monolingual children: A longitudinal DTI study. PLoS ONE, 10(2).

Navarro, A. (1998). Phonetic effects of the ambient language in early speech: Comparisons of monolingual and bilingual learning children. Miami: University of Miami.

Petitto, L., & Holowka, S. (2002). Evaluating attributions of delay and confusion in young bilinguals: Special insights from infants acquiring a signed and spoken language. Sign Language Studies, 3(1), 4–33.

Smith, F. (1990). To think. New York: Teachers College Press.

Zurer Pearson, B. (2008). Research comparing monolinguals and bilinguals. In A step-by-step guide for parents: Raising a bilingual child (pp. 241–286). United States: Living Language.

Additional resources on the advantages of bilingualism

- What speaking two languages does to the brain

- Read this before you call the speech and language therapist!

- Bilingual options – a site run by Dr Susan Dopke, speech pathologist and consultant in bilingualism.

- A second language gives toddlers an edge – 2011 article published in Science Daily.

- Bilingual adults have sharper brains– summary of a recent study.

- The benefits of multilingualism – article by Micheał Paradowski, Institute of Applied Linguistics, University of Warsaw.

- Know more than one language? Don’t give it up! – article by Rebecca Callahan, Associate Professor Bilingual/Bicultural Education at the University of Texas at Austin.

- Flores, A., and Soto, R. (2010). Bilingual is better: Two Latina moms on how the bilingual parenting revolution is changing the face of America. United States of America: Bilingual Readers.

- Why bilinguals are smarter – opinion piece from The New York Times Sunday Review.

- Bilingualism delays the onset of Alzheimers symptoms – 2010 article published in Science Daily.

The importance of rich speech input

You can only transmit the emotional values of a language in your own language… if you start with English there is bad and good, and the ten nuances in between drop away. And in Dutch I have those nuances… transmitting my limited English to the children would be limiting their general development.

Dutch mother living in Christchurch

In recent years, several studies have highlighted disparities in children’s language abilities when starting primary school, while arguing that highly developed language skills are an important predictor of schooling success (Fernald et al., 2013; Hart & Risley, 2003). These types of studies typically also show a negative correlation between socioeconomic status and language development, such that children from lower socioeconomic families tend to also have less well-developed language skills by school-starting age. This phenomenon has been referred to as the ‘Word Gap’, and parents have been encouraged to attempt to close this gap by increasing the total amount of talking they do with their young children (Hart & Risley, 2003).

More recent research has drawn an important distinction between the quantity and quality of parent–child language patterns, showing that quality of speech in fact plays a far greater role in language development than does quantity (Rowe, 2012). The current emphasis is therefore on encouraging ‘rich speech’ at home, such as by having involved conversations about things beyond the here and now, for example.

This has important repercussions for bilingual families, most particularly for parents with low proficiency in the language of schooling. It is much easier for parents to have rich, fluid and varied conversations with their children in a language in which they feel confident and comfortable, and therefore more realistic to expect that this will be the language they use to build strong linguistic foundations for their children (Unsworth, 2015).

Well-meaning professionals occasionally suggest or encourage speaking only the majority language at home for immigrant or other minority language speakers, particularly if they feel the children’s proficiency in the majority language needs a boost. Evidence suggests that increasing the use of the majority language in the home for minority language-speakers does not increase children’s proficiency in that language (Hammer et al., 2009; Paradis, 2011). Any such recommendations are misinformed and likely to be very detrimental to the development of the minority language.

See Growing Up with Two Languages for more information.

References

Fernald, A., Marchman, V. A., & Weisleder, A. (2013). SES differences in language processing skill and vocabulary are evident at 18 months. Developmental Science, 16(2), 234–248.

Hammer, C. S., Davison, M. D., Lawrence, F. R., & Miccio, A. W. (2009). The effect of maternal language on bilingual children’s vocabulary and emergent literacy development during Head Start and kindergarten. Scientific Studies of Reading, 13(2), 99–121.

Hart, B., & Risley, T. (2003). The early catastrophe: The 30 million word gap by age 3. American Educator, spring, pp. 4–9.

Paradis, J. (2011). Individual differences in child English second language acquisition: Comparing child-internal and child-external factors. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism, 1, 213–237

Rowe, M. (2012). A longitudinal investigation of the role of quantity and quality of child-directed speech in vocabulary development. Child Development, 83(5), 1762–1774.

Unsworth, S. (2015). Quantity and quality of language input in bilingual language development. In E. Nicoladis & S. Montanari (Eds.) Lifespan perspectives on bilingualism (pp. 136–196). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter/APA.

Additional resources on the importance of rich speech

- Why talking to little kids matters – TEDx video by Anne Fernald, a leading researcher on infant-directed speech.

- Why should parents talk to their children in their native language? – article by Ana Paula Mumy, speech-language pathologist and multilingual mother.

- How quality helps babies’ language development grow

- Quality is crucial to language skills – summary of recent research findings.

- Talking to promote your child’s language skills – written by Meredith Rowe, Harvard School of Graduate Education.

Materials for teachers

Information for families preparing to start school or Early Childhood education

When a child with little or no knowledge of the language used is preparing to start school or pre-school, children and their parents can be concerned that the child will not be able to communicate their basic needs. The sheet shown here is intended as inspiration for material that could be sent home to families before the child starts school. The parents can talk to the child about the words and concepts on the sheet, and all the child has to do at the initial stages is to point at what they want to say. Parents are responsible for the child’s knowledge of the home language. Educators can take that role for the language of schooling. It is important that parents do not feel that they should abandon the home language in favour of the school language.

Download Starting schoolLinguistic landscape

In Growing Up with Two Languages, the importance of the linguistic landscape is mentioned. The linguistic landscape of a learning environment in a school or early education centre is an expression of the formal and informal language policies in place there. Enhancing the linguistic landscape can be an easy way to ensure that students and their families feel that they and their languages are welcome and expected in the context.

The tools presented here in video tutorials can be used by educators to enhance the linguistic landscape of a learning environment.

Word Cloud

Little Story maker

QR-codes

You can read more about linguistic landscape in educational contexts (sometimes called schoolscapes) in the works listed below.

Dressler, R. (2015). Sign geist: Promoting bilingualism through the linguistic landscape of school signage. International Journal of Multilingualism, 12(1), 128–145.

Gorter, D., & Cenoz, J. (2014). Linguistic landscapes inside multilingual schools. In Challenges for language education and policy (pp. 163–181). New York: Routledge.

Cenoz, J., & Gorter, D. (Eds.). (2015). Multilingual education. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gorter, D. (2018). Linguistic landscapes and trends in the study of schoolscapes. Linguistics and Education, 44, 80–85.

Harris, L., Cunningham, U., & Davis, N. (2018). Languages seen are languages used: The linguistic landscapes of early childhood centres. Early Education, 64, 24–28.

How to generate a word cloud

A word cloud is used to visually represent text data. Different font sizes and colours are used to show how often different words appear in the text.

This tutorial will help you understand and generate word clouds.

Creating a word cloud using wordclouds.com

The following video tutorial will help you use this word cloud generator.

ABSWordCloud

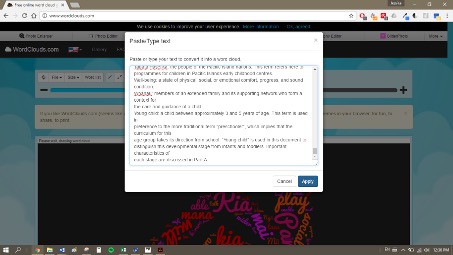

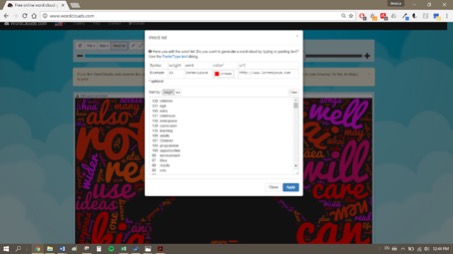

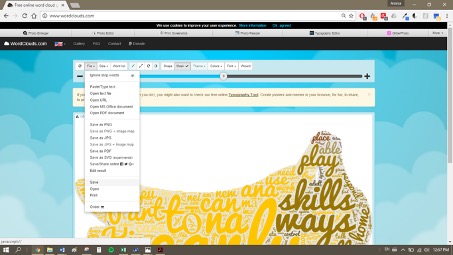

In case you found any difficulties learning from our video tutorial, given below is a step-by-step guide on how to create a word cloud using WordClouds.com and add text to photos on a mobile device (e.g., smartphone or tablet) using the app Textgram. The screenshots in this guide show the layout in Google Chrome on a PC. This will differ slightly from a mobile device.

- Enter http://www.wordclouds.com/ into your web browser and hit Enter.

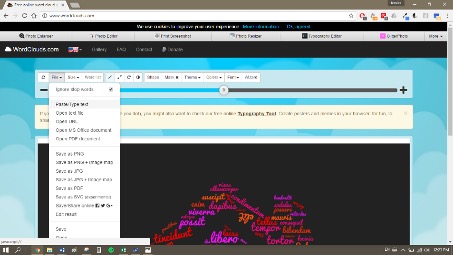

- Select file and select an input method for the text your word cloud will be created from. (In this example, we are going to paste the text from another document.)

- Copy the text you want to create a word cloud from;

and paste it into the text box in WordCloud.com.

- Select Apply and your word cloud will be generated (this may take a few moments).

- To edit the size or remove a word from your cloud, select Word list. The number represents how many times the word appears in the text. The more times a word appears, the bigger it will appear in your word cloud. Increase or decrease the number depending on how large you want the word to appear in relation to other words. To remove a word (e.g. a function word like ‘the’) delete that line from the word list.

- You can edit your word cloud by:

- Adjusting the -/+ slider which changes the size of the words in your cloud.

- Tightening or widening the gaps between words, rotating words, or inverting the image so the words appear in the background and the shape is blank.

- Changing the shape of your word cloud, the colours used, or the font.

- When you are happy with the way your word cloud looks, select File > Save to save the file to your computer. You can now print the image or add to documents as required.

Digital storytelling using ‘Little Story Creator’ for Apple devices

Little Story Creator

This tutorial will help you use ‘Little Story Creator’, a digital storytelling tool that can create a bridge between home and a school or an early childhood education centre, especially for children growing up with more than one language around them. It was produced by Kendall and Jess, our Summer Scholars at the UC LATL-lab with the support of the National Science Challenge “A Better Start – E Tipu e Rea”. This is one of a series of resources produced by the LATL-lab for Early Years Educators.

LATL-lab summer scholars also created a step-by-step guide on how to create a storybook using ‘Little Story Creator’ for Apple devices.

Using Little Story Creator: A step-by-step guide

Follow the instructions given below to create your own digital story using Little Story Creator.

- In your Apple App Store search for, and install ‘Little Story Creator’

- Open the application and click on the + sign in the top right corner and add a new story. Here you can name your story with the keypad.

- Your story will appear in the home page as shown in the picture below. Click on your story to begin creating it.

- From here, follow the steps provided on the application to create and edit your story. For example:

- Choose a background.

- Add existing photographs to each page by clicking the camera icon and allowing access to your devices camera roll OR take photographs and videos on the spot by allowing access to your device’s camera.

- Add a title and text to each page by clicking the ‘Tt’ button.

- Add and record audio to each page by clicking the microphone button.

- To add a new page to the book or duplicate the current page of the book click the page icon.

- To delete any existing work click on the trash can.

- To add pre-existing stickers to a page, click on the smiley face icon and choose from the list of stickers.

- To draw freehand on a page click on the pen icon, choose a colour and begin drawing by touching the screen.

- An eraser is provided next to the pen icon to delete any unwanted drawings.

- When you are finished your story and exiting the ‘creation’ mode, press the home button in the top left corner. Save and exit.

- When you have returned to the home screen of the application, click on your chosen story to read and review your creation.

How to create a QR code – QR Code Generator

QR Code Generator – step-by-step guide

QR Code Generator

This video tutorial will help you generate QR Codes effectively. It was produced by the UC LATL-lab with the support of the National Science Challenge “A Better Start- E Tipu e Rea”

A step-by-step guide on how to create a QR code using the website QR-Code-Generator.com, is given below. Follow the instructions carefully to generate a QR Code effectively.

- Enter http://www.qr-code-generator.com/ into your web browser and hit Enter.

- Copy the URL of the web page or YouTube video you would like your QR code to direct people to.

- Paste the link into the box under Website (URL) and select Create QR code.

- When your QR code has been generated, select the green button (this will now say Download). A pop-up window will appear which can be closed using the X in the top right corner.

- A zip file named qr_code will appear in your downloads. Double click to open the zip file which contains a JPG of your QR code. You can now add this JPG to your document.

Stories for professionalss

Below are some quotes taken from interviews carried out for the ‘bilingual teens’ ITML project. Click on the links to hear people talking about their experiences and/or thoughts on the fact that they speak a minority language at home. If you are a professional working with bilingual families or you just want to get in touch, please contact us via our Facebook page. We’d love to hear from you!

Chinese mother 2

Chinese mother 2 - professional quote 1

Q: As she needs to learn several languages, do you think it influences her schooling? I mean, learning languages occupies her time.

I believe learning a language happens in daily life, you can learn it in every moment. So I don’t think there is a conflict between learning a second or third language and schooling.

Dutch daughter 1

Dutch daughter 1 - professional quote 1

Q: How has that bilingualism, that Dutch influenced your English at school, do you think? Or did it have no effect?

Yes that’s a bit difficult to… for me, to figure out. For example when I… I went to pre-school before I went to primary school and there, for the first year, I did not want to speak at all. I did not say a word. And the teacher there was rather worried and told my parents: “You really have to take her to a speech and language therapist.” And my parents said: “Nonsense! At home she never stops! There she rattles on!” But I don’t know if that was simply because I was shy. Because I was very shy when I was a little child. Or because I did not know the language well.

But when I had a friend at pre-school, then I just rattled on in English so I had no problem. Yes I have no idea what caused it [not speaking for a year at pre-school].

Dutch mother 1

Dutch mother 1 - professional quote 1 - Teacher

I think that the fact that the children… although they did not normally speak Dutch, but that they learned Dutch… that cognitively it was very good for them. All four have… do their university studies at A, A+ level. Very well… and they were good at school… and I believe that is thanks to being bilingual. My father used to say that learning languages was “good gymnastics for the brain”. And I am sure that because the children went from Dutch to English and back again… read a book in one language, and in the other language… that that was very good for their cognition.

Dutch mother 1 - professional quote 2 - Teacher

I fear a lot of people still think: “Oh, now we are in a new country and now we have to speak English.” And I have seen that even with people my age and I see it with parents of other language communities who come to me as ESOL tutor: “Shouldn’t we speak English with our children at home?” And it is not always easy to convince them: “No, continue to speak Korean or Dutch or whatever at home. That English will come at school.” Many parents appear to think: “Now we are here we have to speak exclusively English.” I fear this is still the case although things are much better now than 20 years ago.

But I have also seen that some teachers, primary school teachers at school, see those children who come from elsewhere as a problem. Then they come to an ESOL tutor like me and say: “No wonder the child cannot keep up, they speak Chinese at home.” And I think, “Those teachers have not quite kept up with new developments. It isn’t because the child speaks Mandarin or Korean at home… It is not bad for them.” But when some parents get feedback like this from the class teacher… they no longer know what to do. They will believe the teacher and try to [speak English at home]… so then you get broken English as a home language. So the children lose their heritage language, but don’t get English either. Very sad.

Dutch mother 1 - professional quote 3 - Teacher

We have three sons. The eldest spoke most Dutch as I spoke Dutch to him. Then it became a problem. When he went to childcare centre he already spoke Dutch as we had been back to the Netherlands. He spoke in full sentences. He went to childcare centre and the teachers there did not understand him. And he wet his pants because he had to go to the toilet and they did not understand. He cried and he cried. Look, then you think… and I was in the play centre and the supervisor said it was impolite of me to speak Dutch.

French daughter 1

French daughter 1 - professional quote 1

Q: Do you think that because you were brought up with the French and English, do you think it had a positive impact on your schooling?

Yeah. I think especially with languages and anything with words. I think I’m more proficient even in English, than if I had just been brought up just with English. I don’t know… I had more of a learning and an understanding of language and words in general. Even if I look at a big word in English that I don’t know then I can think: “Oh that looks a bit like that word in French, so it’s probably from French” and then I can guess what it means. I can sort of figure that out. And other European languages I think too, would be easier to pick up.

Q: How well did you achieve in school in general, and in English as a subject?

Umm… really well actually [laughs]. It’s sort of my ‘thing’ really, languages.

French father 2

French father 2 - professional quote 1

I think that if both parents are French, or French speakers, it is crazy to speak English just because we live in an English-speaking country. Our language is still French, in this case, and it’s the same in any other language. My daughter has friends whose parents are Catalan, so they speak Catalan at home, and I find this completely normal.

German parents

German parents - professional quote 1

P1: So when I had him in Palmerston North I had Kiwi friends, but when I was with him, on my own, since he was my first born, I talked only German to him. So when he started the Steiner Kindergarten in Palmerston North he couldn’t speak English at all. But he learnt it in three months, and he was fluent. That’s fine but I suppose that’s already the decline of the other language I think. I can remember when I talked German some mothers at play centre would say, you know, “but we don’t understand what you are saying to the child!” so they felt slightly offended or something. So I actually talked in English to him but this wasn’t probably right either.

Korean daughter 1

Korean daughter 1 - professional quote 1 - My Recording

Q: A recent government report said immigrant parents should speak English at home all the time so that their children could learn English better. How do you feel about that? If your parents spoke English at home, maybe all the time, do you think your English language proficiency would be improved?

I don’t think it would make much of a difference. Because I reckon, even at home, the amount you communicate with your parents at home compared to the amount you communicate in English to people outside of home is way bigger than usual. Because your parents have work. And I think if that happened – if my parents spoke more English than Korean – my Korean would just die away. Because they’re the main source of Korean I use.