Chapter 6

Quiz

- 6.1 Multiple choice questions

- Identify arguments that are rationally persuasive for a particular subject.

- 6.2 Multiple choice questions

- Identify the best refutation by counterexample.

Worked Through Examples

Argument reconstruction and commentary

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-u6Ss640-kU

This video is an interesting one to reconstruct because it clearly forms an argument, but the pictures do much of the work. The points that the arguer wishes to make are clarified by text, but the text is intermittent and incomplete, and requires filling out.

This 2 minute 35 second YouTube clip presents an argument that sometimes cycle lanes are not safe to use. This is presented explicitly at 0.03. There is a further implicit conclusion to draw from this, which is that when a cycle lane is not safe to use, it should not be used. While the cyclist does not make this point explicit, that further conclusion is clear from the way the cyclist behaves. The point of the clip is for the cyclist to justify the fact that he or she is not riding in the cycle lane. Thus the final conclusion of the argument is ‘Sometimes cycle lanes should not be used by cyclists’.

In terms of the wider context of the argument, it is common for motorists to complain that cyclists do not use cycle lanes provided, and the cyclist is likely to be responding to such comments.

The cyclist gives us five reasons to think that sometimes cycle lanes are not safe to use.

- At 0.22 the cyclist identifies the way the bus has crept into the cycle lane.

- At 0.29 the cyclist notes that the cycle stencil marking on the road does not fit in the cycle lane.

- At 0.50 our attention is drawn to the way cycle lanes stop and start.

- At 1.40 the cyclist notes that the risk of the doors of parked cars opening requires the cyclist to move out into the road.

- At 2.19 the cyclist notes the risk posed by cycle lanes around roundabouts.

Reasons 1 and 2 are evidence for the single claim that sometimes cycle lanes are too narrow to use safely.

The preliminary conclusion is:

C1: Sometimes it is not safe to use the cycle lane,

and the final conclusion is:

C2: Sometimes the cycle lane should not be used by cyclists.

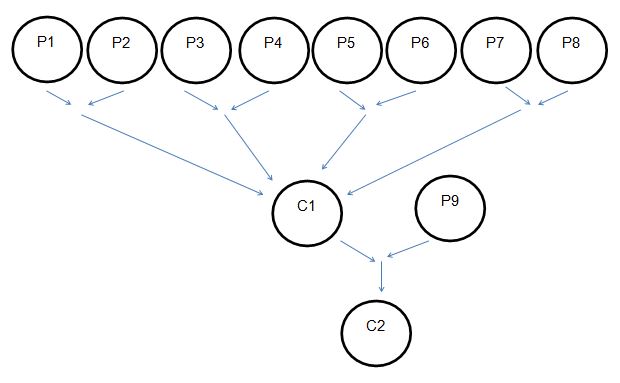

The basic structure of the argument is as follows:

Figure 1

Reconstruction:

P1) Sometimes the cycle lane is too narrow to be safely used by cyclists.

P2) If the cycle lane is too narrow to be safely used by cyclists, it is usually safer for cyclists to use the main road lane than the cycle lane.

P3) Sometimes cycle lanes stop and start.

P4) If a cycle lane stops and starts, it is usually safer for a cyclist to use the main road lane than the cycle lane.

P5) Sometimes there is a risk for cyclists being hit by suddenly opening doors from parked cars.

P6) If there is a risk for cyclists being hit by suddenly opening doors from parked cars, it is usually safer for a cyclist to use the main road lane than the cycle lane.

P7) Cycle lanes on roundabouts are not safe.

P8) If there is a cycle lane on a roundabout it is usually safer to use the main road lane than the cycle lane.

__________________

C1) Probably, sometimes it is safer for cyclists to use the main road lane than the cycle lane.

P9) If it is sometimes safer for cyclists to use the main road lane than the cycle lane then at those times cyclists should use the main road lane.

__________________

C2) Probably, sometimes cyclists should use the main road lane.

This reconstruction can be diagrammed as follows:

Figure 2

At 0.03 the arguer presents the claim that cycle lanes are sometimes good to use, and at 1.09 it is pointed out that they are okay to use when they are wider. It would be possible to reconstruct a further argument for this. However, the fact that cycle lanes are sometimes safe to use doesn’t support the main conclusion, so I have treated it as extraneous material.

At 2.26 the arguer suggests blaming cars for the door zone problem. Once again this is extraneous because it does not support the main conclusion.

The original reasons given by the arguer have been converted into propositions.

The use of ‘too narrow’ in P1 is vague, but it is difficult to replace it with anything more useful. It is clearly a claim about safety, but as that is brought out in the rest of the premise, the vagueness does not present a huge problem. That vagueness will be returned to when the truth of the premise is discussed below.

Premises P1, P3, P5 and P7 all give reasons why cycle lanes may be unsafe to use. The point, however, is not just that cycle lanes may be unsafe, it is that the type of safety problem involved means that the cyclist will be safer using the main road. This has been brought out in C1. Why do we need to say that the cyclist will be safer rather than safe? It is clear that there are also safety risks in the main road lane. Cyclists can still be hit by traffic there. The point must therefore be one of comparative safety.

In seeking a connecting premise to get from P1, P3, P5 and P7, a single generalisation could have been used, but this option was rejected. So, a connecting premise which would render the argument valid is ‘If a cycle lane is not safe, the cyclist will be safer in the main road lane’. However, something this general is clearly false, and is therefore uncharitable. If the entire road were flooded (or awash with lava), the cycle lane would be unsafe, but the main road would be no safer. The comparative safety of the main road is dependent on these specific safety concerns, which the arguer thinks the main road will avoid. Thus I have added a separate connecting premise for each reason, rather than a single generalisation.

A cyclist can still be killed or hurt on the main road, even when one of the hazards mentioned occurs in the cycle lane. Each connecting premise has therefore been softened to the claim that in such circumstances the main road is usually safer.

The inference from C1 to C2 has been presented as if it is free from exceptions. The arguer is attempting to justify the claim that there are occasions when a cyclist should be on the main road and not in the cycle lane. It is reasonable to suppose that the arguer thinks that such an argument will apply whenever these safety concerns arise.

Assessing the force/validity

P2, P4, P6 and P8 employ conditionals where the consequent usually follows. Conclusion C1 therefore does not follow from the premises with complete certainty, and the argument is not valid.

The argument is forceful, however. If premises P1–P8 are true, C1 is more likely to be true than not. Further, because there are four independent reasons for accepting C1, C1 follows with a very high degree of probability.

The inference from C1 and P9 is a valid one: the probability is not any further diluted by this inference.

This is therefore an inductively forceful argument.

Assessing the soundness

It seems unlikely that the video has been doctored, and it seems unlikely that any of the situations have been set up for the purposes of making a misleading video. In fact, my experience of road use tells me that the situations videoed are not unusual.

P3 is demonstrated as true by the evidence on the video: we see this happen. So, supposing the video is authentic, as argued for above, these premises are true.

P5 is not demonstrated on the video itself, as no car doors open while the cyclist is passing them. However, the risk that this could happen is clear, and there are sometimes reports in the newspapers of cyclists being hurt or killed by car doors opening. So it seems reasonable to suppose that P5 is true.

P7 is not argued for here, but I think it is true. The danger for a cyclist on a roundabout is that if the cyclist goes around the outside of the roundabout, a motorist approaching the cyclist from behind and trying to leave the roundabout may fail to give way to the cyclist. The danger is that roundabouts are not designed to deal with multiple lanes, especially for traffic travelling at different speeds. So I think P7 is true.

The truth of P1 is difficult to assess because ‘too narrow’ is a little vague. There is a suggestion on the video for how to determine what counts as ‘too narrow’, in that if the cycle stencil does not fit, the arguer thinks that indicates that the lane is too narrow. It is clearly possible to make a cycle lane which is ‘too narrow’, in the sense that it can be narrow enough to be unsafe. And the arguer has given us an example to show where that causes a safety problem, in the form of the video showing the bus encroaching on part of the lane. So P1 is likely true.

P2, P4, P6 and P8 all make a connection between the reasons offered by the arguer and the conclusion he or she wishes to draw about the main road lane sometimes being safer than the cycle lane.

They all rest on an assumption that when certain kinds of dangers are presented by the cycle lane, the main road lane will be safer. It is true that when in the main road lane the cyclist will avoid the dangers of car doors, and will avoid the danger posed by being cut off on a roundabout.

The danger of a lane which stops and starts is probably caused by the danger of merging with traffic which is not expecting cyclists to merge. That danger can be avoided by remaining in the main lane, for then no merging occurs. The danger of narrow lanes presumably lies in the way that traffic may be tempted to pass when there is not in fact enough room to do so. Once again, that temptation would be avoided if the cyclists were in the main road lane, for then there would clearly not be room to pass.

The difficulty with assessing P2, P4, P6 and P8 is that they all claim that the main road lane will be safer. This is harder to assess, because there are also some safety risks there. Perhaps the only way to assess whether it is really safer would be to collect traffic accident statistics to find out whether cyclists are more often hurt, or more badly hurt, when in the main lane to avoid cycle lane hazards, or when in the cycle lane containing those hazards.

However, as C1 makes the moderate claim that sometimes it is safer to be in the main lane, it seems that we have been given a good enough reason to accept that. Further, although each of P2, P4, P6 and P8 make the softened claim that the main road lane is usually safer in their respective circumstances, they each provide support to C1, making the moderate claim made in C1 extremely likely to follow. So C1 is very likely true on the basis of the evidence presented.

It is more difficult to be confident of the truth of P9. P9 claims that if the main road lane is safer, then that is where a cyclist should ride. However, someone could argue that safety should not be the main consideration here. The convenience of other road users is also important. So P9 is at least controversial. P9 is the support needed for the main conclusion, and it would really need an additional argument to support it. However, as it doesn’t occur explicitly, it is not surprising that no support is offered for it.

So, the inference to C1 is inductively sound, but the further step to C2 requires further investigation to establish the truth or falsity of P9.

Sample commentary

Original argument:

Commenting on the projected doubling of Auckland’s population by 2031, Opinion writer David Gibbs says “we can all fit in”. But if we all fit in, how are we going to move? The transport system is stuffed, and improvement is unlikely in the short term. The answer is to stop population growth.

(Ian Williamson, NZ Herald, short letters, 13 May 2013)

The context is that someone else has claimed that there is no difficulty in fitting twice the population of Auckland into the area. Williamson is responding by pointing out that if the population expanded in such a way, the population would be unable to move around successfully. The answer, he says, is to prevent the population from growing.

Basic argument

The final conclusion of the argument is that we should stop Auckland’s population from growing.

The reason for that is that if the population grows, while people may be able to fit, they won’t be able to move.

A reason is also given for that: the transport system is stuffed, and improvement to it is unlikely in the short term.

So the most basic form of the argument is like this:

P1) The transport system is stuffed.

P2) Improvement to it is unlikely in the short term.

_____________

C1) They won’t be able to move.

_____________

C2) We should stop population growth.

The reconstruction process:

In P1 we need to supply a more complete proposition: the transport system in question is Auckland’s. ‘Stuffed’ is a slang term, and needs to be replaced by something more informative. What does Williamson mean here? Most likely he means that the transport system is unable to move people around effectively (either trips take too long, or are too difficult). The complaint is not just that there is something wrong with the transport system, but that what is wrong is tied to what the population is. That is, the size of the population being catered to is an important part of the way this argument functions. We can bring that out in this premise, and rephrase P1 as ‘Auckland’s current transport system is inadequate for its current population’.

P2 also requires some rephrasing. First of all, we need to clarify what is being referred to: Williamson is speaking of Auckland’s transport system. It is this which he thinks will not improve. To be charitable, Williamson’s point is unlikely to be that the transport system will not improve at all. Minor improvements to transport systems occur all the time. Williamson’s point is that there will not be any significant improvement. This gives us ‘Auckland’s transport system is unlikely to undergo significant improvement in the short term’.

‘The short term’ is vague. What does Williamson mean by it? One time span relevant to the argument is the time between the letter being written and 2031, which is the estimated time it will take for the population of Auckland to double. We could build this in to P2, yielding P2` ‘Auckland’s transport system is unlikely to undergo significant improvement before 2031’. Alternatively, we could decide that it is the doubling of the population which is relevant, and build this in, yielding ‘Auckland’s transport system is unlikely to undergo significant improvement before the population of Auckland doubles’. Williamson expects that these will happen at around the same time, but there is the possibility that they will not.

The difficulty with making P2` so specific is that such specificity may have an undesirable effect on argument assessment in terms of the soundness of the argument. Suppose that significant improvements to the transport system are finished in 2032. In such circumstances P2` would be technically true, but this goes against the spirit of the argument. If the improved transport system is not finished in 2031, but is finished in 2032, Williamson’s argument might turn out sound, but the intent of his argument would not be met. We therefore have a good reason for keeping this part of the argument somewhat vague.

If the time span Williamson has in mind is that between writing the letter and 2031, or until the population doubles, why does he use the expression ‘in the short term’? Eighteen years would not necessarily be seen as ‘short term’.

The answer is that Williamson is thinking of how long it takes to make changes to transport systems. Significant transport system changes take time: first plans must be made, and funds raised, and highways, bridges and tunnels (or alternatives) take time, usually years, to build. I think it is thus reasonable to allow Williamson his use of ‘in the short term’, so long as we remember what approximate timespan he is thinking of when we come to assess the truth of the premise.

In C1, ‘they’ is clearly intended to refer to those living in Auckland. The author does not mean that people who live in Auckland will literally be unable to move, but that if there is a substantial increase in Auckland’s population the transport system will be unable to cope. Thus C1 can be reworded as ‘Auckland’s transport system will be unable to cope with a substantial increase in the city’s population’.

The reconstruction then requires the connection between P1–P2 and C1 to be made explicit. This could be done by means of a conditional of the form ‘If Auckland’s transport system is inadequate for its current population, and it does not undergo significant improvement in the short term, then that transport system will be unable to cope with a substantial increase in the Auckland’s population’. However, it seems unlikely that this is a point specific to Auckland. A better connection makes a point about cities in general: ‘If a city’s transport system is inadequate for its current population, and it does not undergo significant improvement in the short term, then that transport system will be unable to cope with a substantial increase in the city’s population’.

Because this premise is a general one about cities, we then need a premise which points out that Auckland is a city (P4).

A connecting premise is also needed between C1 and C2. C1 says ‘Auckland’s transport system will be unable to cope with a substantial increase in the city’s population’, and C2 claims ‘Auckland’s population should not be allowed to substantially increase’. Because C2 is a prescriptive conclusion and C1 is a descriptive one, the relevant connecting premise must contain a prescriptive element.

The connection could be made by means of a conditional: ‘If Auckland’s transport system will be unable to cope with a substantial population increase, then Auckland’s population should not be allowed to substantially increase’. However, there doesn’t seem to be anything specific to Auckland about this point: to the extent it is true, it seems to be true of cities in general rather than of Auckland in particular. Thus the connection can be made: ‘If a city’s transport system will be unable to cope with a substantial population increase, then the population of that city should not be allowed to substantially increase’. This is the simplest possible general connection which can be made. Using a simple connection is justifiable here because Williamson has given us no indication for any other way he intends the connection to occur. Invoking some other connection would therefore involve arguing for Williamson, rather than representing his argument, and so would be overcharitable.

Given the above discussion, the argument can be reconstructed in the following way.

Reconstruction:

P1) Auckland’s transport system is inadequate for its current population.

P2) Auckland’s transport system is unlikely to undergo significant improvement in the short term.

P3) If a city’s transport system is inadequate for its current population, and it does not undergo significant improvement in the short term, then that transport system will be unable to cope with a substantial increase in the city’s population.

P4) Auckland is a city.

_______________

C1) Probably, Auckland’s transport system will be unable to cope with a substantial increase in the city’s population.

P5) If a city’s transport system will be unable to cope with a substantial population increase, then the population of that city should not be allowed to substantially increase.

__________________

C2) Probably, Auckland’s population should not be allowed to substantially increase.

Logical assessment

The inference from P1–P4 to C1 is not valid: the presence of ‘unlikely’ in P2 makes C1 merely probable. The inference is a forceful one: if P1–P4 were true, C1 would be more likely to be true than not.

The inference from C1 and P5 to C2 is a valid one, and the probability of C2 is not diluted any further than that of C1. Therefore the argument as a whole is forceful, and ‘Probably’ has been added before C1 and C2.

Soundness

The argument is forceful, so if the premises are true it will be inductively sound.

The truth of P1 partly depends on what is meant by ‘inadequate’. Auckland’s transport system certainly has problems, and they are the kind of problems which are common in large, relatively spread-out cities. Auckland’s transport difficulties are also exacerbated by the way it straddles a harbour, which causes unavoidable bottlenecks. It is true that during rush hour it can take a long time to get anywhere in Auckland. Like many big cities, it is probably over-reliant on private vehicle use, which is a rather inefficient way to travel around. And its spread-out nature means that people wish to travel long distances. It is probably fair to call Auckland’s transport system ‘inadequate’, both in the sense that it could be better than it is, and in the sense that it suffers certain geographical features which make it difficult to travel around efficiently.

P2 claims that Auckland’s transport system is unlikely to undergo significant improvement in the short term. Some improvements are made, of course. But the complaint that there will be no significant improvement is more likely to be accurate. Auckland’s chief bottleneck, at the Harbour Bridge, can only be alleviated by the building of another bridge or a tunnel, and the construction of either of those would take considerable time. Other significant improvements, such as the construction of further highways, or a train system for public transportation, would also take considerable time. Williamson is right that such changes are unlikely to be completed over the next 15–20 years, which, as discussed above, seems to be more or less what Williamson meant by the ‘short term’. If such changes were going to be completed in that time frame, they would probably need to be agreed upon already, and they are not. This leaves Auckland with only relatively minor roading projects and tweaking of public transport arrangements, and Williamson seems to be discounting such minor improvements as not significant enough to make a difference. If the population does indeed double, it does seem that such minor changes will be insufficient to improve the ability of the population to move around the city quickly and easily.

So, I am willing to accept P2 as true, given its likely intended meaning.

At first glance P3 seems obviously true. If the transport system is currently not coping, and what it has to deal with is only going to get worse, then if they don’t improve it, its ability to cope will get worse.

However, this assumes that other things, such as the requirement to be transported around the city, will remain the same. In fact they may not do so. For instance, there may be an increase, in the future, in the number of people who are able to work from home, and who therefore do not need to move around the city at all. It is possible that the technology that enables this will change faster than transport systems can be changed. For instance, it has been noted that 40 per cent of rush hours trips in Auckland are education related: this is people travelling to school and university. If people became more willing to attend their local school, or substantially more university courses come to be taught online, then there might be substantially less need to travel around the city. At the rate at which technology is currently changing, as well as people’s willingness to use that technology, there might be substantially less need to travel within the time period Williamson regards as ‘short term’.

However, given what we currently know about people’s needs, P3 is likely to be true. Further, no matter how information technology changes, it is still true that there will be some need for people to be able to travel around Auckland city in 15–20 years’ time. Even if more people work and study from home in the future, if the population doubles it seems likely that the transport system will have trouble coping without substantial improvements.

P4 is a well-known fact. If someone doubts it, it can be easily established by consulting a map of New Zealand, or looking up Auckland in an encyclopedia.

Given the likely truth of P1–P4, and the force of the inference to C1, C1 is likely to be true, although we should keep in mind the slight reservations we had about P3.

P5 claims that if a city’s transport system will be unable to cope with a substantial population increase, then the population of that city should not be allowed to substantially increase. Assessing the truth of this claim is difficult. On the one hand, we can see that having a major city around which people cannot move would be a significant disadvantage for that city. It would prevent business from operating properly, and would make life very unpleasant. It may indeed be worth avoiding. On the other hand, the consequent seems very strong. One might wonder if there are any circumstances which would justify employing draconian measures to prevent population increase. Someone might argue, for instance, that people have a right to choose where to live, and we should not interfere with that right. In that case, it might be that even though an increase in population will cause all sorts of problems, it is not the kind of thing that we should act to prevent.

Or, it may be the case that although some population control measures are not justifiable, other, gentler measures are justifiable. So, while ordering people to leave a city might be wrong, it may be acceptable to adopt policies which actively encourage people to live elsewhere. If what Williamson has in mind is such policy changes, it may be possible to give an argument justifying P5.

At this point, however, I am unsure whether or not P5 is true. Without a justified belief in that premise, I cannot rule the argument sound.