Chapter 1: Introduction to geopolitics

The goal

The task of this chapter is to define geopolitics. Seemingly, that shouldn’t be difficult. But saying what is, and therefore what isn’t, geopolitics is itself an act of politics. To cut a long story short, most definitions of geopolitics do two things that we want to challenge:

- they limit geopolitics to the actions of countries (and not businesses, terrorist groups, social movements, and other sets of individuals); and

- they don’t include a good understanding of what is meant by the “geo” in geopolitics. In other words, what’s the geography that makes geopolitics different from, say, “world politics” or “international politics”?

If we want to have a definition of geopolitics that takes the “geo” seriously, then we need to think like a geographer.

Geography: Not just a quiz category

I’m originally from Great Britain. I did my undergraduate degree in geography at the University of Newcastle-Upon-Tyne in the late 1980’s. At the time, geography was one of the most popular degrees in the country. It remains popular in Britain, as well as European countries, Japan, China, India, and Australia. But geography is not a popular undergraduate degree in the United States. Many universities in the United States do not have a department of geography. Rather than being seen as an academic discipline, geography in the United States can be seen as a category in quiz games! Misunderstanding geography as simple knowledge about rivers, oceans, and mountains has led to a poor understanding of what is the “geo” in geopolitics. Let’s correct that misunderstanding.

Human geography is about how all of our actions as individuals and as groups (such as a protest group or a country) try to make geographies. For example, a nationalist group tries to change the geography of existing borders to make a new country. And the motivation for national separatist groups is the existing geography of borders – a geography they think is unfair. In this chapter we’ll explore this as the “mutual construction of space and society.”

We are interested in how politics shapes geography; that’s the basis of our definition of geopolitics.

Defining geopolitics

This is the definition of geopolitics I created for this book:

“The struggle over the control of geographical entities with an international and global dimension, and the use of such geographical entities for political advantage”.

My motivation for creating this definition was to include an understanding of geography as a social process in definitions of geopolitics. In other words, it’s a way of taking seriously the “geo” in geopolitics.

One more thing, we need to think of geopolitics as a combination of two separate but related actions:

- geopolitical practice – or actions such as committing a terrorist attack or stationing troops in another country; and

- geopolitical representation – or the way that geopolitical practices are described to make them appear as just or moral acts, while portraying the actions of one’s enemies as aggressive and unjustified.

Not your grandparent’s geopolitics

My definition of geopolitics is a far cry from how geopolitics was first thought of in the late nineteenth century; what we call classic geopolitics. Classic geopolitics is still with us. Much of what you read about how dangerous the world is and how “your” state must react is the current version of classical geopolitics.

Most academics studying geopolitics, including myself, do not like classic geopolitics. It is seen as being non-objective and used to promote the agenda of one country – usually involving military force. Instead, academics take a critical view of classic geopolitics. They do so by either challenging the assumptions and language of classic geopolitics – what we call critical geopolitics. Another challenge to classic geopolitics is to see the world from the perspective of the vulnerable and relatively powerless – this is known as feminist geopolitics.

In this book we engage the topics of classic geopolitics by a mixture of critical and feminist geopolitics.

A roadmap for you to use as you travel through the book

On the home page we spoke of this book as a conceptual toolkit to understand world politics. We need quite a few conceptual tools in the toolkit. The book is organized in a way to help you learn how to use one tool at a time. Once you’ve learned about each tool we conclude the book by showing how our complex world requires using a number of conceptual tools to understand any one issue.

Resources

Here are a table and a figure to help you see where you are on the learning journey from concept to concept.

Download ZIPTable_Chapter_Practice_and_Rep.pdf

The table shows how we will talk about geopolitical practice and geopolitical representation in each chapter.Figure 1.2.pdf

The figure is a flow chart to show how learning about a set of conceptual tools in one chapter connects to learning about other conceptual tools in the following chapter.Figure 1.2.pptx

Here is a PowerPoint version of the flow chartChapter 2: A framework for understanding geopolitics

Defining geopolitics

Just to remind you, this is the definition of geopolitics I created for this book:

The struggle over the control of geographical entities with an international and global dimension, and the use of such geographical entities for political advantage.

My motivation for creating this definition was to include an understanding of geography as a social process in definitions of geopolitics. In other words, it’s a way of taking seriously the “geo” in geopolitics.

What geographies?

The definition of geopolitics is about controlling geographic entities. We concentrate on five types of entities:

- Places – the settings of everyday life.

- Regions – similar areas of the world defined by culture or institutions.

- Networks – the way flows of things, people, and ideas move from place to place.

- Scales – from places, through regions, countries, and the global; what happens at one scale is connected to other scales.

- Territory – the way geographic spaces are controlled for political reasons.

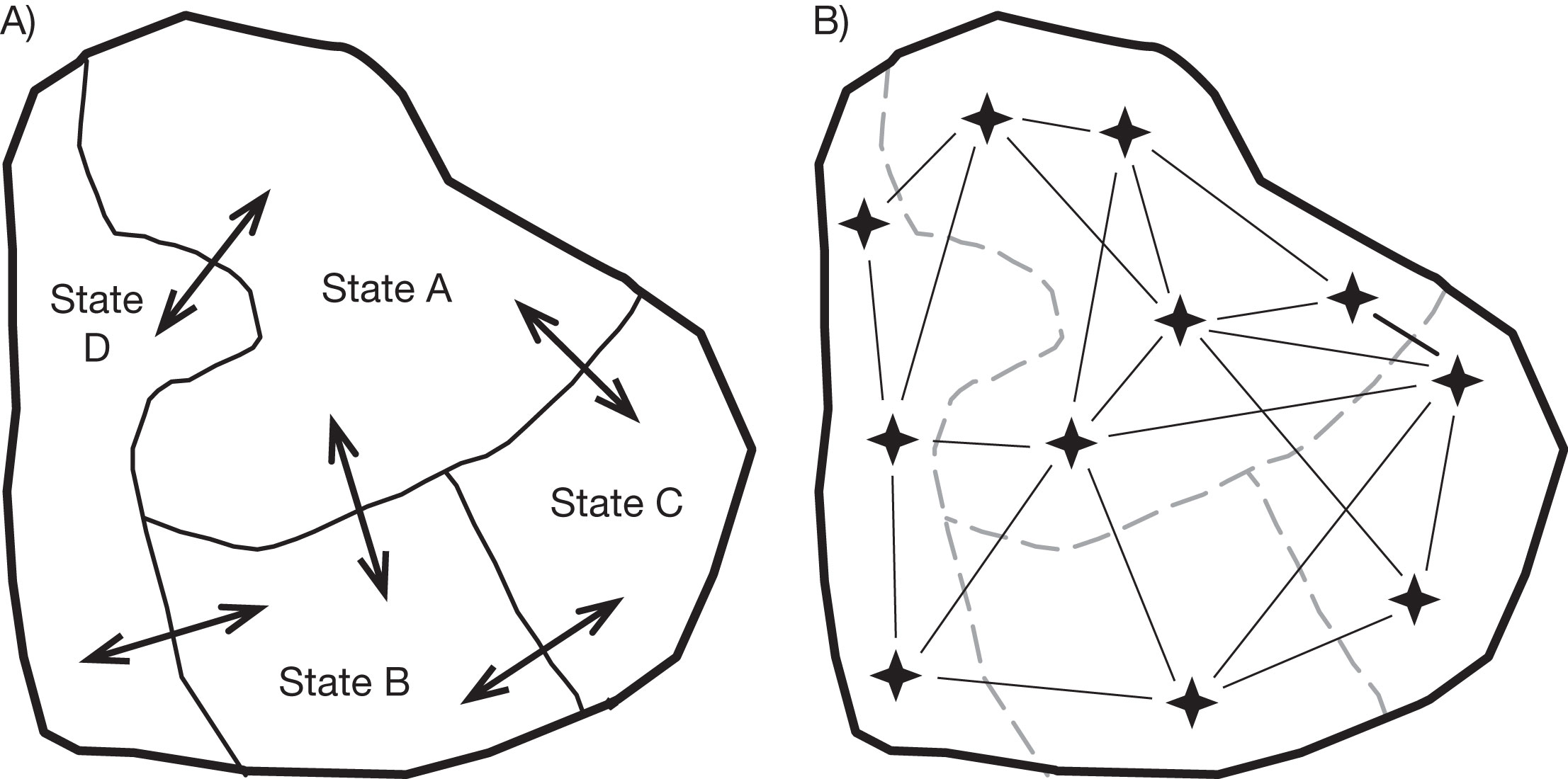

These entities are all connected. This abstract figure shows the interaction of places, territories, and networks. Can you apply this abstract view to a real-world example?

Think of a conflict (past or present) that interests you and use the table below to see how struggle over the five geographic entities were part of the conflict.

|

Example |

Place |

|

Region |

|

Networks |

|

Scales |

|

Territory |

|

These entities are dynamic. Because the geographic entities are made through struggle, they will change depending on who wins and who loses. The continent of Africa has been the location of different expressions of territory over the course of history, from imperial territories to the map of countries today.

Power

As geopolitics is a struggle then we must think about power.

We discuss three forms of power:

- Material power – or the possession of “things” such as military strength, economic strength, and resources.

- Relational power – how material power only makes sense when it is put into operation. For example, having an aircraft carrier (material power) only has affect once it sails the oceans and is seen by other countries as a threat.

- Ideological power – the way that the use of material power through forming relations is justified and explained. There is power if the actions of one country, say, are seen as legitimate and don’t raise eyebrows while similar actions by another country are seen as being “wrong” or “illegitimate.”

Understanding power as material, relational, and ideological helps us see how geopolitics as practice and geopolitics as representation are connected. Every action requires a representation.

Using the same conflict that you used to think about the five geographic entities, identify how the participants used the three forms of power.

|

Example |

Material Power |

|

Relational Power |

|

Ideological Power |

|

Did you find that different forms of power were more likely to be used when trying to control different entities?

Structure and agency

Our definition of geopolitics requires us to think about one more concept: structure and agency. Geopolitical practices are what we call agency – the act of doing something – such as one country imposing sanctions on another country. But agency does not occur in a vacuum. It occurs within sets of rules and norms that we call structures. These structures appear at many different scales. For example, political parties must act (an example of agency) within the electoral rules of the country (a structure). Another example is how member countries must make decisions and live up to commitments (agency) within the rules of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

Using the same conflict that you used for the previous tables can you identify the agents involved, the structures they were operating within. Once you’ve done that think about how the structures enabled and constrained the agents.

|

Structures |

Enabling |

Constraining |

Agent 1 |

|

|

|

Agent 2 |

|

|

|

Do it yourself

Our definition of geopolitics is about struggle and geography. Think of an ongoing current event and try and gain further understanding by applying the concepts of power or geographic entities.

Here are three examples from the Aggies Geopolitical Observatory to help you.

Power: https://chass.usu.edu/aggiesgo/news/russia-navalny-protests.

Scale: https://chass.usu.edu/aggiesgo/news/chile-subway-scales.

Network: https://chass.usu.edu/aggiesgo/news/coronavirus-flows.

Chapter 3: Geopolitical agency

This chapter introduces the concept of geopolitical codes. Geopolitical codes are the way we can understand geopolitical practices, or different forms of agency.

Geopolitical codes

We define geopolitical codes as “the manner in which a country orientates itself towards the world.” Each country defines its geopolitical code through five main calculations:

- Who are our current and potential allies?

- Who are our current and potential enemies?

- How can we maintain our allies and nurture potential allies?

- How can we counter our current enemies and emerging threats?

- How do we justify the four calculations above to our public, and to the global community?

Use the table below to think about the five calculations of two countries that you find interesting. Perhaps you could choose one quite powerful country and one that is less powerful.

|

Allies |

Enemies/threats |

Means to address allies |

Means to address enemies/threats |

Justifications |

Country 1 |

|

|

|

|

|

Country 2 |

|

|

|

|

|

The means of geopolitical codes

There are many ways (or means) that country can engage with its allies and enemies. These range from violent (bombing or assassination, for example) to establishing cultural relations (such as encouraging scholars and students to come to your country to study).

Thinking about different means requires us to think about the three forms of power we learned about in the previous chapter. Use the table below to identify how the different forms of power are relevant in the different means one country uses in its engagement with another country. Perhaps you can think about this for how the same country engages with an ally and a threat. Are different means and different forms of power more relevant depending upon whether the relationship is friendly or hostile?

Choose one of the countries that you used to complete the table above. Identify 3 means within their geopolitical code and how they are examples of one or more of the different forms of power, or a combination of the forms of power.

|

Material Power |

Relational Power |

Ideological Power |

Combination of Powers |

Means 1 |

|

|

|

|

Means 2 |

|

|

|

|

Means 3 |

|

|

|

|

Scales of geopolitical codes

All countries have a geopolitical code that lays out how they engage with their immediate neighbours. Some countries construct a geopolitical code that is regional – how they engage with countries beyond their neighbours. For example, Saudi Arabia has a geopolitical code that is concerned with the whole of the Middle East. A handful of countries have a geopolitical code that is global in scope. Great Britain had such a code during the nineteenth century through World War II. From the around the beginning of the twentieth century to the present the United States has had a global code. Over the past few decades China has developed a regional geopolitical code and is increasingly thinking at the global scale.

Look at the map of China’s Belt and Road Initiative used in this chapter. What scales are portrayed on this map? Which scales are absent? Identify a place (city or town) that is not present in this map and see how the BRI connects it to other scales.

Dynamism of geopolitical codes

Geopolitical codes are dynamic, but not completely fluid. Countries have to recalculate who are their allies and enemies, and how to deal with them. We see this recalculation in regular security reviews. Mostly these calculations identify a recurring pattern of threats and alliances. But not completely as new threats emerge, or old threats can be seen as allies. At the end of the Cold War some countries that had been allies of the Soviet Union, and enemies of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) became members of the alliance. It was initially thought that Russia would become an ally of the West, but it has remained hostile to NATO.

It seems like we are in a particular moment of geopolitical flux. China’s regional power and its growing ability to act globally have meant that other countries have had to alter their geopolitical codes in response.

Feminist geopolitics

The concept of geopolitical codes is very useful in understanding how countries act geopolitically. But the concept can mean that we fall into the trap of classic geopolitics and see geopolitics in a narrow way – simply the actions of countries, especially the most powerful ones.

Feminist geopolitics helps us avoid that trap. For every decision by a country to act in a certain way there are impacts on people. For example, bombing campaigns lead to civilian casualties and sanctions can lead to food shortages or growing unemployment. On the other hand, fostering allies through cultural exchanges can lead to study-abroad opportunities for college students.

For the codes you found in the table above – think how different groups within the countries may benefit or suffer from the particular means of geopolitical codes. To answer this question, you will have to think about how social policies and cultural norms create inequalities within the country based on gender, race, religion, sexuality, and ethnicity. Once you’ve done that you can think about how the geopolitical codes may make such inequalities worse or improve them.

Non-state actors

Up to now we’ve used geopolitical codes to understand how countries act. But our definition of geopolitics allows us to think about how other groups may struggle to control geographic entities. We call these groups non-state actors. Examples include terrorist groups, social movements (such as Extinction Rebellion, focused on global climate change), and even unorganized groups such as refugees.

Am I right in suggesting that we can use the concept geopolitical codes to understand the decision of non-state actors? Choose an example and see if the five elements of a geopolitical code are applicable.

Choose a non-state actor that interests you and use the table below to see if you can identify the calculations of a geopolitical code. Use these examples, or lack of them, to decide whether we can use the geopolitical code concept to understand the agency of non-state actors. How would your examples and decision change if you were to compare a violent non-state actor (e.g. a terrorist group) with a social movement (such as Extinction Rebellion)?

|

Example |

Identification of allies |

|

Identification of enemies/threats |

|

Means to engage allies |

|

Means to engage enemies/threats |

|

Justifications for identifications and means |

|

Do it yourself

There are ample ways to apply the concept of geopolitical codes to current affairs. You may use the concept to break down the actions and decisions of countries into the 5 different calculations in a code and see how they connect to each other. You may also see how a country’s code operates at different scales, by using different means that involve the use of different forms of power. Or, you may use the approach of feminist geopolitics and look at the impact of a geopolitical code upon civilians, especially the most vulnerable.

Here’s an example from the Aggies Geopolitical Observatory to help you. Note how it talks about geopolitical codes as being relational:

https://chass.usu.edu/aggiesgo/news/nuclear-weapons-and-geopolitical-codes.

Chapter 4: Justifying geopolitical agency

This chapter continues our discussion of geopolitical codes by focusing upon the fifth calculation: how the identification of allies and enemies, and the means to address them, are justified. The way geopolitical codes are justified has been the focus of critical geopolitics, and emphasizes the role of geopolitical representations.

Though we distinguish between geopolitical practice and representation, the two are inseparable. Every geopolitical practice must be represented in a certain way. Every country or non-state actor represents their geopolitical actions in a positive way. For example, terrorist groups claim their actions are necessary in the pursuit of some just cause. And countries always describe their military actions as steps towards peace and security. Another purpose of geopolitical representation is to claim that the actions of others are threatening and outside what is described as “normal.” Hence, a terrorist group can claim that its actions are provoked by an aggressive country, and that country justifies its actions against the terrorists who they claim are “cowardly” and “uncivilized.”

Geopolitical representation is an example of what social scientists call discourse: or the way that language comes to normalize certain power relationships and marginalizes other agents. Discourse is the expression of ideological power, or the way that more powerful agents can set the agenda of geopolitics. One example is how the United States and other Western countries portray the current organization of world politics as operating for the common good, while portraying China’s actions as disruptive and selfish. Another example is the way that social movements have challenged long-standing assumptions about the benefits of fossil fuels and brought the question of global climate change to the political mainstream.

You can’t escape geopolitics

Geopolitical representations are all around us. They appear in speeches of political leaders and in government documents. But we mainly experience political representations when we don’t think we are. Geopolitical representations appear in all forms of popular culture: films, books, songs, etc.

That means that even when you’re trying to relax and forget about the real-world, you are immersed in geopolitics. You are bombarded by geopolitical representations whenever you watch a TV series or a watch a film that is seemingly 'make believe.'

The goal of critical geopolitics is to make us think about these representations. By identifying geopolitical representations, we can be reflective or even critical of the descriptions of the world, and the actions of countries and non-state actors, that we largely take-for-granted. Don’t believe me? Well, then let’s play geopolitical word association! Have a friend or fellow student say between 5 and 10 countries quite quickly. Don’t take time to write out the name of the country, just write down the very first word that comes to mind for each country.

Here’s twelve countries just to help you get started:

- United States

- North Korea

- France

- Mexico

- Afghanistan

- China

- Turkey

- Iraq

- Japan

- ISIS

- Iran

- Great Britain

Ask yourself where these words came from. Did they come from scholarly books or lectures? Probably not. Did they come from characters or story lines in films or TV series? That’s more likely.

Consider the film releases in your hometown or on a streaming service over the past, say, six weeks. Who were the enemies or “baddies” portrayed in the films? Do they represent, either overtly or subtly, real world countries or other geopolitical agents? Who do the “goodies” represent? What were the nationalities of the actors who played the 'goodies' and the 'baddies'?

Think of the geopolitical code of one or two countries that interest you (if you did the exercises from the previous chapter you may continue with the same countries). What are common words or phrases used to describe the country? In what ways do these words or phrases justify or challenge their geopolitical practices?

|

Common Representations |

How the representations justify the country’s actions |

How the representations challenge the country’s actions |

Country 1 |

|

|

|

Country 2 |

|

|

|

Critical geopolitics meets feminist geopolitics

Scholars of feminist geopolitics have pointed out that geopolitical representations in films and TV series often rely on particular portrayals of men, women, and different races. In the book we discuss the role of Katniss Everdeen in the Hunger Games films. Often women are portrayed as weak and vulnerable and in need of male protection. Usually that protection requires acts of violence. More recently films like the Hunger Games series and Black Panther have tried to challenge established portrayals of race and gender.

Consider the gender roles in the films and how different racial groups are portrayed in the films you thought about earlier. In what ways do these representations justify certain actions in the films, especially the use of violence.

|

Representation of Gender Roles |

Representation of Racial Groups |

How the representations justify actions |

Country 1 |

|

|

|

Country 2 |

|

|

|

The dynamism of geopolitical representations

In the previous chapter we saw that geopolitical codes are dynamic. Geopolitical representations must also change to keep up with changes in the identification of allies and enemies, and the means to deal with them. In the book I use a series of maps to show different parts of the world, especially the Middle East and China have become increasingly important in the annual State of the Union speech given by the President.

Here are just two maps comparing the speeches of President George H.W. Bush with those of his son, President George W. Bush.

Why not conduct your own analysis by counting how often certain countries have been mentioned in recent speeches? Has the geographic focus changed? Can you see a general trend over time? And what of the tone of the speeches? Have recent speeches been more focused upon threats rather than building friendly relations? You can access the speeches at The American Presidency Project:

www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/presidential-documents-archive-guidebook/annual-messages-congress-the-state-the-union#Table%20of%20SOTU

Do it yourself

Geopolitical representations are all around us. News stories of a current events usually contain a quote from a politician or expert that contains a representation. Also, the language used in the story will include representations. Remember, ideological power is influential because we take these representations for granted. In other words, they’re easy to skip over. You have to think like a critical geopolitician to find them.

Here is an example from the Aggies Geopolitical Observatory to help you:

https://chass.usu.edu/aggiesgo/news/russia_protests.

Resources

Download ZIPFigure 4.3.jpg

Figure 4.3 Map of the world identifying countries mentioned in President Ronald Reagan’s State of the Union speeches.Figure 4.4.jpg

Figure 4.4 Map of the world identifying countries mentioned in President George H.W. Bush’s State of the Union speeches.Figure 4.5.jpg

Figure 4.5 Map of the world identifying countries mentioned in President William Clinton’s State of the Union speeches.Figure 4.6.jpg

Figure 4.6 Map of the world identifying countries mentioned in President George W. Bush’s State of the Union speeches.Figure 4.7.xls

Figure 4.7 Graph with y-axis of percentage of references to allies or enemies and x-axis of Presidential administrations to show changing proportion of such references across time.Website_Tables_Chapter4.pdf

And here are the tables in pdf formatChapter 5: Embedding geopolitics within national identity

My very first research project was on the topic of nationalism. It was my undergraduate honours project back in 1990 at the University of Newcastle-Upon-Tyne. Specifically, it was about English nationalism; a topic that has grown in importance with Brexit and questions about the stability of the political geography of the United Kingdom. Sometimes I wonder what my career path would have been like if I’d kept studying the topic!

Why does nationalism interest me? One reason is that I grew up in a household that believed that “England was the best” – it was a nationalist household. In fact, it wasn’t just my family; the media and politicians pushed that message, and still do! Another reason is an academic question: it’s intriguing to me that an ideology that is so vacuous is so pervasive and powerful. Nationalist beliefs rest on myths about the history and people of a country, and yet for centuries pretty much everyone in the world has nationalist beliefs. Billions of people believe in nationalism, even if most do it sub-consciously. And nationalism is the most common thing we fight, kill, and die for. That’s quite a geopolitical impact!

What word should I use?

As a student of geopolitics I’m sure you’d like to know you’re using the right words! Up to know, I’ve used the word “country” to refer to entities like the United States, China, etc. The one exception is the term “non-state actor.” That gives us a clue that when referring to countries we should use the word “state.”

The interesting thing is that we don’t use the word “state” when we should do. Instead, we tend to use the word “nation” or even “nation-state.” But a nation is a very different thing from a state. A nation is a cultural group, and a state is a country. And nation-state implies that there is just one nation within a state, and that’s just not the case.

So why is common usage of the terminology wrong? Perhaps it’s because we equate “state” with things like bureaucracy and taxation, while “nation” is much more romantic and mythical. And people seem motivated to fight and die for a connection with the romantic and mythical rather than the bureaucratic.

In this chapter we talk about two forms of nationalism that we call top-down and bottom-up nationalism. Though we introduce them separately they work together to make people nationalist: meaning they carry a belief that they belong to a cultural group (a people or nation) and that gives them a right to a piece of territory that becomes 'their' country.

Top-down nationalism

One myth of nationalism is that there has existed a set of nations since primordial times that come to realize a right to live in a piece of territory – or have their own state/country. In fact, the historic process is one in which states have gained control over a piece of territory and then created a sense of nationalism so that those living in that country feel a sense of unity. This creates a geography of inclusion and exclusion – those who seemingly “belong” in a country and those who “don’t.” Nationalism can do nothing but create a sense of difference – a political geography of “us and them.”

So, it is the institutions of the state that create a sense of nationalism, and because of this we are all nationalists to some degree.

How and where did you learn your national history?

Think of the settings (home, school, etc.) where you were exposed to this history and the form the history took (books, films, lessons, etc.). Write down two or three of the key ingredients of the history and what “moral” or story they may tell about the particular national character. Write down two or three key historic events that are usually ignored or played down in the national history of your country.

How do these lesser-discussed events contradict the portrayal of the national character you identified from the dominant narrative?

In what ways are questions of race and colonialism prominent or marginalized in national narratives? How do different discussions of race lead to different visions of the essence of national identity?

Bottom-up nationalism

We tend to believe that nationalism is what other people do; bad, hateful, and violent people. This is the other type of nationalism, that has been given the name 'ethnic cleansing.' We avoid the term 'ethnic cleansing' because it is a geopolitical representation that tries to normalize a tragic form of geopolitics.

Bottom-up nationalism comes about when politicians and people search for a 'pure' nation-state, one that contains just one cultural group. Other groups are seen as endangering and weakening the country and should be removed through the violence of expulsion and eradication; in other words, forcing people to flee or killing them. Sometimes this type of nationalism can involve an attempt to change so that members of the same cultural group in neighbouring countries become situated inside the 'pure' country.

We illustrate this process of expulsion, eradication, and expansion through an abstract set of maps depicting 'circle people' and 'triangle people' and their attempts to create nation-states that are 'pure' – excluding others.

Can you find examples of bottom-up nationalism today or in past conflicts?

|

Expulsion |

Eradication |

Expansion |

Country 1 |

|

|

|

Country 2 |

|

|

|

Geopolitical codes and nationalism

Bottom-up nationalism is a form of geopolitical code. Luckily, it’s relatively rare. Instead, geopolitical codes are the actions of states, and the representations that justify codes are built on a foundation of nationalism.

The geopolitical representations of nationalism are often gendered. The nation is often seen as feminine, by using the terms motherland or homeland. And it must be defended by male violence. This tendency leads to the dominant of ideology of militarism; or that geopolitical codes inevitably require violent military responses.

Consider the geopolitical code of countries that interest you. You may refer back to activities in previous chapters and use the same countries if you wish. In what way is the geopolitical code militaristic? In what ways are the justifications for geopolitical actions based on gendered geopolitical representations?

|

Examples of militarism in the geopolitical code |

Use of gendered representations in the geopolitical code |

Country 1 |

|

|

Country 2 |

|

|

Do it yourself

Nationalism is always in the news. Some media stories are about bottom-up nationalism and others top-down nationalism. Can you find examples of both, and perhaps see how the two forms of nationalism are connected?

Here are examples from the Aggies Geopolitical Observatory to help you.

https://chass.usu.edu/aggiesgo/news/monumental-shifts-1

https://chass.usu.edu/aggiesgo/news/human-rights-myanmar.

Chapter 6: Territorial geopolitics

As a reminder, the goal of this book is to provide you with a conceptual toolkit to understand world politics. Our definition of geopolitics emphasizes struggle over the control of geographic entities. One of those entities is territory: the way areas of our planet are claimed by geopolitical agents who then attempt to control them. The world political map displays the world as a mosaic of territories that we call countries, or states.

But the world political map of countries is a very simplistic representation of the world. First, often governments do not have complete control of their territories. For example, swathes of the Sahel region, including the countries of Mali and Burkina Faso, are controlled by jihadists and not the recognized government. Second, the boundaries between countries are often fuzzy either by choice or through lack of control. Third, the geopolitical role of territory must be understood in relation to another of our geographic entities: networks. Territory is controlled to prevent flows into it. For example, preventing the smuggling of illegal drugs, or the issue of documented and undocumented migrants – including refugees.

Definitions

I use these three definitions in this book.

- Boundary refers to the dividing line between political entities: the “line in the sand” if you wish, that means you are in, say, Germany if you stand on one side and Poland if you stand on the other.

- Border refers to that region contiguous with the boundary, a region within which society and the landscape are altered by the presence of the boundary.

- When considering neighbouring states, the two borders either side of the boundary can be viewed as one borderland. This is especially useful when looking at the cross-boundary interaction between two states.

In everyday language, the word “border” is usually used in the same way that I use “boundary.” That’s usually OK, but in this book we distinguish between boundary and border so that we can see the construction of two types of regions, borders, and borderlands.

Making territories, boundaries, and borderlands

Our definition of geopolitics is based on the human geography understanding that geographies are made by social activity. The emphasis of our definition of geopolitics is that this making is often a matter of struggle, including violence. There are a number of implications of seeing territory and boundaries as a product of struggle.

- No form of territorial organization is “natural.” Though we live in a world of territorial states there were other forms of political organization prior to the formation of states. And maybe there will be a different form of political organization in the future.

- Creating a pattern of boundaries and territorial control creates winners and losers. Some groups may be happy with the current geography of boundaries but others will not be. This is why we have disputes over the geography of the course of a boundary (such as the one between India and China), and the politics of separatism (such as Scottish nationalism).

- The legitimacy of a state depends upon its ability to control its boundaries.

- States may choose to have porous boundaries, such as the free flow of people and goods within the European Union.

- Managing a boundary effectively can lead to peace. The opposite is also true.

- Borderlands are a geopolitical feature that emerges from how people interact across boundaries, and states do not have full control over this process.

- In sum, the geopolitics of territories and boundaries is inseparable from the geopolitics of networks and flows.

Boundaries and geopolitical codes

Every country must consider the behaviour of its neighbours when constructing a geopolitical code. There are a host of boundary disputes and other issues that can lead to tensions across, and because of, boundaries.

We use the fictional country of Hypothetica to illustrate the range of boundary disputes.

I have provided some examples of the disputes occurring in Hypothetica. Think of current or historic cases to find your own examples.

Boundary conflict |

My example |

Your example |

Internal separatist movement |

Nagorno-Karabakh within Azerbaijan, but ruled by ethnic Armenians |

|

Unified location of ethnic group |

The Kurdish people, especially with regard to Turkey. |

|

Minority group overspill |

Ethnic Russians in the Baltic states |

|

Seasonal migration |

Tuareg movement across Mali’s boundary |

|

Interpretation of watershed line |

Aksai-Chin area disputed between India and China |

|

Meandering river as boundary |

Colorado and Rio Grande rivers relating to US–Mexico boundary |

|

Median line of lake as boundary |

Lake Nyasa/Lake Malawi between Tanzania and Malawi |

|

Upstream-downstream tensions |

The Mekong River and, as an unusual case, the Nile River |

|

Oilfield spanning the boundary |

Kuwait/Iraq and Greece/Turkey |

|

Important mineral resource |

Uranium deposits in Democratic Republic of the Congo |

|

Land-locked state |

Nepal and Bhutan and their relations with India and China |

|

Threat to border settlements |

Israeli cities near the Gaza strip in the south and Lebanon in the north |

|

Territoriality of the sea

Countries also establish control over the oceans. In fact, one of the most pressing geopolitical issues is China’s claims over parts of the South China Sea that other countries believe are theirs.

Consider the geopolitical codes of one or two countries that have claims to the oceans. Are there particular means of geopolitical codes that are prevalent in maritime disputes? How do the particular forms of power appear in these disputes? Are particular geopolitical representations used to justify actions in maritime disputes?

|

Means of the geopolitical code |

Manifestation of forms of power |

Content of geopolitical representations |

Country 1 |

|

|

|

Country 2 |

|

|

|

Do it yourself

Boundary disputes and the tenson between territory and flows are always in the news.

Here are some examples from the Aggies Geopolitical Observatory to help you:

https://chass.usu.edu/aggiesgo/news/india-china-boundary.

https://chass.usu.edu/aggiesgo/news/malabar-india-geopolitical-codes.

https://chass.usu.edu/aggiesgo/news/israel-boundaries-flows.

https://chass.usu.edu/aggiesgo/news/hong-kong-boundaries.

Chapter 7: Network geopolitics

Classic geopolitics identified one type of agent: the state. Reference to geopolitics in the media usually talks about inter-state competition. But focusing upon states provides a partial understanding of geopolitics. Geopolitics is also a matter of the construction of networks and the struggle to control them. Geopolitics is also a matter of the interaction between states and networks. Some of these interactions are wanted by states – such as trade, tourism, and investment. But other interactions are seen as threatening by states – such as illicit trades (drugs, human trafficking, etc.), and terrorist networks. One more thing: people participate in politics through networks, and not just by being a citizen of a particular state.

In sum, the geographical entity of networks is one venue of geopolitics.

Can you make a list of different types of networks and the agents involved in creating them? There may well be more than one agent involved in any one network. In what ways would states welcome the existence of the network and in what ways would states see the network as a threat?

Networks and geopolitical agents

A number of geopolitical agents are involved in the geopolitics of making and controlling networks. Considering networks expands our understanding of geopolitics by identifying social movements, criminal organizations, terrorist groups, and businesses as agents involved in the construction of geographical entities.

But do not think of geopolitics as a simple either/or between the geopolitics of territories and networks. First, states are actively involved in creating networks – alliances between states (such as NATO) can be seen as a diplomatic network. States rely on networks of investment and trade (including the arms trade). And geopolitical codes of states address ways to counter flows through networks: such as terrorist groups, movements of refugees and undocumented migrants, and illicit trades.

States use networks as part of their geopolitical codes. Think of two countries (perhaps ones you have used in previous exercises) to identify different means within the codes; those means involve agency within networks and territories, and the interaction between the two geographical entities.

|

Means of geopolitical code |

Network |

Territorial |

Interaction between territory and network |

Country 1 |

|

|

|

|

Country 2 |

|

|

|

|

Networks and other geographical entities

One interesting area of exploration is to consider how the geopolitics of a network can only be understood by seeing how other geographical entities are implicated in the struggles. An abstract representation of networks shows how they connect places (known as nodes in a network) that are located in different territories.

The example of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) helps us understand how a network of trade and investment is made by connecting places across the globe, and how those places are transformed by being part of the network. The BRI has been identified as a “threat” by other states, such as the United States, Australia, Japan, and India, resulting in a change in their geopolitical codes. In collaboration, these states have created the geopolitical representation of a new strategic region: the Indo-Pacific. Finally, the role of the BRI in the development of places in a network that spans oceans and continents shows that multiple scales (from the local, through regions, to a change in the global pattern of trade and investment) need our attention.

Use the table below to think of your own example of a network and how it connects to political agency in other types of geographical entities.

|

Agents |

Places connected |

Territories where the places are located |

Regions implicated or constructed |

Scales, and how they are connected |

Network example |

|

|

|

|

|

Types of network geopolitics

In the book we examine different types of network geopolitics. Here are activities related to three types: terrorism, social movements, and cyberwarfare.

The Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START) programme at the University of Maryland is a good source to explore who is committing terrorism, under what motivations, and why START publishes their Global Terrorism Review every year. You can find it, and much more information, by going to their homepage at www.start.umd.edu. Think about the changing geography of terrorism over the years. Are certain countries persistently the venue of terrorism? What new countries are emerging as sites of terrorism and why? And what of the motivations for terrorism? And how have states constructed their geopolitical codes in response to the geography of terrorism and the motivations behind terrorism? Another way of thinking about this is to explore how the actions of states are used in the geopolitical representations of terrorist groups to justify their actions.

Consider a social movement of your choice, perhaps one that you are active in. Use the table below to consider how the movement makes connections within itself and with other movements. These connections are an expression of the social movement as a network. But how do they connect people in different places and at different scales?

|

Network connections |

Places connected |

Scales connected |

Social movement example |

|

|

|

The Center for Strategic and International Studies keeps a running score of “Significant Cyber Incidents.” Go to their website at www.csis.org/programs/technology-policy-program/significant-cyber-incidents and browse through the attacks that are reported. How many involve private companies rather than government agencies? How many would you consider “crime” rather than “geopolitics”? Why the distinction and how does it relate to our definition of geopolitics and who we consider to be geopolitical actors? In Chapter 3 we noted that geopolitical codes include economic means as well as political and military actions. If that is the case, how are cyber incidents involving industrial espionage factored in to our understanding of contemporary geopolitics?

Do it yourself

There are many ways in which networks are a venue for geopolitics. You can consider how states and non-state actors use networks, or see them as a threat. Also, think about how network geopolitics interacts with territorial geopolitics.

Here are some examples from the Aggies Geopolitical Observatory to help you.

Networks and social movements: https://chass.usu.edu/aggiesgo/news/wetsuweten-networks.

Networks and COVID-19: https://chass.usu.edu/aggiesgo/news/coronavirus-flows.

The legacy of colonial networks: https://chass.usu.edu/aggiesgo/news/botswana-homosexuality-network.

Technology networks and geopolitical codes: https://chass.usu.edu/aggiesgo/news/huawei-us-gepoliticalcodes.

Chapter 8: Global geopolitical structure

One of the organizing concepts in the book has been structure and agency. We introduced agency through the concept of geopolitical codes. Countries and non-state actors have some freedom in defining what they do and how they do it. These choices are the contents of their geopolitical code. However, states and non-state actors do not have complete freedom when considering their choices. They are enabled and constrained by a geopolitical structure.

Two forms of structure are discussed in this chapter. The first is George Modelski’s cycles of world leadership whereby the geopolitical code of the most powerful state in the world sets the global political agenda. States and non-state actors construct their geopolitical codes, to a large degree, depending upon whether they comply with or challenge the world leader’s agenda. The United States has played the role of world leader since World War II. The model suggests that we are in a period when the United States is losing power and the geopolitical codes of other states and non-state actors increasingly challenge the United States.

The second form of geopolitical structure is Immanuel Wallerstein’s world-systems analysis. Similar to Modelski’s model, Wallerstein sees the United States as a global power that has set the political agenda since World War II and is in a period of decline. Wallerstein adds economic competition as a key driver of the process of geopolitical change.

Use this table to think about how the geopolitical codes of one or two countries and/or a non-state actor have changed through the phases of US world leadership.

|

Global War |

Leadership |

Delegitimation |

Deconcentration |

Country 1 |

|

|

|

|

Country 2 or a non-state actor |

|

|

|

|

By considering both Modelski’s and Wallerstein’s ideas we can identify five mechanisms of geopolitical change:

- the preference and availability of world order;

- the formation of coalitions that support or challenge the world leader;

- imperial overstretch;

- competition over new technology; and

- institution building.

Use the table below to identify how the calculations within the geopolitical code of one or two countries and/or a non-state actor provides opportunities or constraints related to these mechanisms.

|

Preference and availability of order |

Coalition membership and challenge |

Imperial overstretch |

New technology |

Institution building |

Country 1 |

|

|

|

|

|

Country 2 or a non-state actor |

|

|

|

|

|

A further way to think about the process of geopolitical change is to consider how the geopolitical code of one country or non-state actor has changed over time because of calculations focused on one of these mechanisms.

Use the table below to identify how the three forms of power operate together within a country’s geopolitical code in relation to one of these mechanisms of change.

|

Mechanism of change |

Material power |

|

Relational power |

|

Ideological power |

|

Do it yourself

Is it more accurate to think of the United States from the early twentieth century to today as a hegemonic power or as world leader? To answer the question, think about the relative weight given to economics versus politics, and self-interest and political duty in the different models. Perhaps you may be able to find examples of both. Is the global “responsibility” of the US as either world leader or hegemonic power solely a matter of rhetoric, or can you also point to particular actions?

The Aggies Geopolitical Observatory contains many essays discussing geopolitical codes. Here are some examples that you can use that allow you to consider how a geopolitical code is made within the context of the mechanisms of change:

https://chass.usu.edu/aggiesgo/news/china-canada-geopolitical-code

https://chass.usu.edu/aggiesgo/news/nuclear-weapons-and-geopolitical-codes

https://chass.usu.edu/aggiesgo/news/malabar-india-geopolitical-codes

https://chass.usu.edu/aggiesgo/news/swedish-geopolitical-code.

Chapter 9: Environmental geopolitics

In this chapter we discuss the environment as a geopolitical structure. The term Anthropocene is used to emphasize that we live in an epoch in which global climate change, the extinction of species, and other major environmental changes are driven by human activity.

The environment raises many interesting geopolitical issues. The first is the question of scale. Geopolitical codes have emphasized national security, but risks of environmental change occur at a scale that transcends states. Second is the way that the geopolitical codes of states have been adapted to include environmental issues. But does this just lead to the national militarization of what are human and global security concerns? Third is the way that states have adopted inter-state responses to environmental issues (especially global climate change), and the resulting tensions between national interests and the constraints imposed by multi-lateral agreements. Fourth is the role of networked social movements, especially the way that social movements have forced states to address global climate change.

Scale and environmental geopolitics

The tension between the regional or global scope of environmental processes and the national agendas of states’ geopolitical codes is seen to be a barrier to agency that can address environmental issues. Use the table below to explore this scalar tension for questions such as food security, access to drinkable water, air quality, sea-level rise, and species extinction (you may choose a different environmental issue that interests you). Also, think about the impacts of these environmental crises on people’s everyday lives in the places they live – and how actions in those places may bring change at broader scales.

|

National response |

Regional response |

Global response |

Place-based activity |

Food security |

|

|

|

|

Access to drinkable water |

|

|

|

|

Air quality |

|

|

|

|

Sea-level rise |

|

|

|

|

Species extinction |

|

|

|

|

Geopolitics and environmental geopolitics

Throughout this companion website I have suggested looking at the geopolitical codes of countries as we have moved through the concepts addressed in the different chapters. Were any of the issues you addressed environmental? If yes, you may revisit them. Otherwise, explore how the countries you have been thinking about have addressed environmental issues, what means have been used, and how the means require the use of different forms of power (material, relational, and ideological).

|

Environmental Issue |

Means within the geopolitical code |

Form of power |

Country 1 |

|

|

|

Country 2 |

|

|

|

Social movements and environmental geopolitics

In Chapter 7 we thought about how social movements make connections within a network and between places and at different scales. Are social movements motivated by global climate change, or another environmental issue that is global in scope, more effective in making connections across networks, places, and scales? How may the connections made by environmental social movements have an impact upon national political agendas?

|

Network connections |

Places connected |

Scales connected |

Environmental social movement example |

|

|

|

Do it yourself

The Aggies Geopolitical Observatory writers have regularly addressed environmental issues. Here are examples using a variety of geopolitical concepts:

Geopolitical codes and climate change: https://chass.usu.edu/aggiesgo/news/us-china-collaboration-climate.

>Energy and ideological power: https://chass.usu.edu/aggiesgo/news/renewable-energy-shifts.

Social movements and climate change: https://chass.usu.edu/aggiesgo/news/thunberg-voice-power.

River basins and geopolitical codes: https://chass.usu.edu/aggiesgo/news/yunnan-myanmar-region.

Chapter 10: Messy geopolitics

The final chapter introduces the idea of “messiness.” That may seem like an odd conclusion. Shouldn’t I be tying things together for you with a nice pretty bow? Engaging geopolitics is not so simple. The idea of the book being a conceptual toolkit helps us understand “messiness,” while also helping us to use it to gain a better understanding of geopolitics.

Each chapter of the book has identified a particular set of concepts to help us understand geopolitics. In this way we have seen that geopolitics consists of different agents and forms of agency that occur within different structures, and combine in our definition of geopolitics: the struggle over the control of geographical entities.

In each chapter I have concentrated on a particular form of agency and/or structure, and particular geographical entities. I organized the book in this way so that you could gain understanding of different agents, structures, and entities one step at a time.

“Messiness” forces us to acknowledge that any geopolitical issue involves many different agents, structures, forms of struggle, and geographical entities. Our conceptual toolkit may allow us to focus on one aspect of the issue by using a smaller set of tools. But understanding the whole issue requires using many different conceptual tools for different purposes. The analogy is in building a house. We need particular tools to wire the kitchen. And we need many more tools and skills to complete the house.

If only “messiness” was our only problem …

Politics of geopolitics

Now that you have a toolkit to engage geopolitics there is something else we must remind ourselves about: thinking about geopolitics in any given way is itself an act of politics. We identified classic geopolitics as the dominant type of geopolitical thought. I criticized that type of thinking for invoking a sense of “us and them” and a tendency towards military conflict. My approach aims to be more objective by understanding why different geopolitical agents do different things given the opportunities and constraints of structures. We are aided in this approach by ideas from critical and feminist geopolitics.

How you choose to approach geopolitics is your choice. But realize that it is a choice that will lead to different understandings of the world. Looking at geopolitics in any particular way is tied to a particular agenda or another. I will take the liberty to say that if you think the world is a mess and dangerous perhaps it is classic geopolitical thinking that has brought us to this situation, seeing as it is the dominant way geopolitics is understood. In other words, classic geopolitics may be the problem and not the solution.

Geopolitics of peace

Recently, geographers have pushed for studying the geopolitics of peace. Academics and commentators tend to focus on crises, especially ones that involve violence. We understand geopolitics as a social process: We make war. In that case, we make peace as well. Arguably we do a good job in making peace as even though there’s always conflict going on most of the world is at some sort of peace most of the time.

Making peace is a social process that occurs at a number of scales, from the individual to the global.

Can you think of a geopolitical struggle that was resolved, past or present, and identify how the process to peace required change at the scales of the peace pyramid?

Pick up the toolkit and go to work …

I hope this book has helped you understand geopolitics. Perhaps you just had to use this book for a class, and think that you’re done with geopolitics. Perhaps you are pursuing a career as a diplomat or military officer. Perhaps you want to go into business. Whatever your current situation and future, you will not be able to avoid geopolitics. I hope this book gives you the confidence to engage geopolitics, to think about geopolitical practices, including those of your own country, critically, and not to take dominant geopolitical representations for granted.

Do it yourself

In previous chapters I have guided you towards the Aggies Geopolitical Observatory (https://chass.usu.edu/aggiesgo) to show you how undergraduate students have used the concepts in the book. Now is the time to take off those training wheels and try something bolder.

Find a news magazine such as The Economist, Atlantic Monthly, The New Yorker, Time, or the colour supplements of the Sunday newspapers. These magazines usually carry longer stories on current conflicts than the daily newspapers and include interviews with the participants and victims. Explore an article of your choice and use the interviews and descriptions of the participants’ circumstances to identify different structures and how they interact. Do the interviews show divisions within particular groups or agents, such as political parties, ethnic groups, etc.? In other words, does the article exemplify how geopolitical agents are not singular?

If you are in a class or other group setting you could do this project with someone else and explore the same conflict using different media sources. This will not only help you in identifying more structures and types of agency, but you may also consider how different media outlets emphasize different structures and types of agency over others. For example, were political parties and state ministries or departments emphasized in one source while protest groups, women’s groups, and other social groups were emphasized in another?