Introduction

Religion, the relationship between humans and a godhead, has been anything but uniform. In the course of time there have been people who found their gods in the natural elements − the sun, the wind, etc. − and people who worshipped human-like beings with supernatural powers - the deities of the so-called pagan Greeks and Romans, for example. And there were people who believed in a unique God, a belief which allowed no other deities. Yet even this monotheism is not without its anthropomorphic elements: God sees, God knows, God loves, God rewards, God punishes, God has a hand. The great medieval theologian Thomas Aquinas held that our human knowledge of God must be by way of human categories of thought − there is no escaping it − and that one must recognize that theology (the study of God) is, of its nature, by way of analogy: that God is Wholly Other.

All three of the great monotheistic religions − Judaism, Christianity and Islam − will be met in the course of this book with emphasis on Christianity, the monotheistic religion of western Europe. These three religions intersected at times during the Middle Ages. Christianity saw itself as the fulfilment of promises made to the Jewish people, and at times Christians not only rejected Judaism but ruthlessly persecuted Jews. Islam also saw itself on a continuum with the religion of Abraham with Mohammed as the last of the prophets. Not only did Islam replace Christianity in many lands (especially in North Africa and Iberia), but it too felt the aggression of Christians, when crusaders claimed the Holy Land. Three monotheistic religions - two of them neighbours and one submerged in the others − shared a belief in a single, all-powerful God, yet each with its own emphases: the Jews with their shared history of a chosen people and belief in a Messiah to come, the Muslims with their stress on the Day Of Judgement, and Christians with a god who was three but one.

The influence of religion on a people’s culture and the corresponding influence of culture on religion are difficult to measure, so interpenetrated did they become. The German and Celtic peoples who were converted to Christianity did not lose their ethnic identities: they were still Germans and Celts but now Christian Germans and Christian Celts. Their ethnicity was bound to influence the different ways in which they expressed their shared Christian beliefs.

Religions can have a history because of their human element. The human beings who are Christians are sentient, rational beings with the power of free choice. They make decisions about their religious lives and the structures that support them. They are capable of magnanimity and outrageous misbehaviour, of sanctity and sinfulness, of prudent judgement and woeful errors. It is their deeds that provide the material for history generally, and it is their deeds in the name of religion that provide the material for ecclesiastical history.

The focus here is on the history of a religion that expressed itself in a church, in this instance the Christian church of western Europe. Some may wish to extend the term ‘medieval’ to include eastern Europe and the world of Byzantium. A more conventional definition is used here, and the history that follows focuses chiefly on the church of the Latin West.

The Christian church was a defining element in medieval society. There were others, of course, but the Middle Ages without the church would not be the historic Middle Ages. It was the one international ingredient which bound together disparate peoples in a shared faith and ritual and a common learned language. Variations there indeed were, but the same Creed was recited at the same kinds of liturgical ceremonies from Iceland to Sicily and in tens of thousands of villages throughout western Europe. The general councils of the church drew members to Lyons, Rome, Vienne, Constance and elsewhere in the only truly international assemblies of the Middle Ages. Theologians and canon lawyers not only spoke the same Latin language, but they discussed the same issues. The existence of local customs and traditions added to the flavour of the religious culture of the times and also served to emphasize the overarching transcendence of the medieval church.

The underlying assumptions about the nature and purpose of life were common currency. A triune God exists and is involved in human affairs. Christ is God and man, who came to earth to redeem the human race. Life on earth is a pilgrimage to another life, where the obvious injustices of this life will be redressed in eternal bliss or eternal punishment. Even Christians who diverted from traditional Christianity − and who were labelled heretics − generally shared the same basic world-view. Scepticism and disbelief, on the evidence, were extremely rare but not totally absent. Yet it was the religious assumptions of society generally, whether questioned or unquestioned, that helped to define the age.

If the medieval church can be said to have a body and a soul, then the external institution pertains to the body and the inner spiritual life of Christian people pertains to the soul. A history of the church cannot limit itself to the institution nor, on the other hand, should it omit the institution or treat it almost incidentally. History records how an institution, which was believed to have been divinely founded, was ruled by human beings, who were not divine, sometimes far from being even spiritual. This institution grew and, as it grew, required organization and rules. From the time that we might want to use the word medieval, perhaps from the sixth century, we can see a network of bishops with one, at Rome, claiming authority over the others. That institution, then, following the mandate to ‘teach all nations’, sent missionaries to Celtic and Germanic peoples. And as these new peoples began to establish political control, the church as an institution made the decision to interact with these new leaders, at times even asserting authority over them. This external church constructed places of worship and places of education, giving the world great churches and universities. The leaders of this institution helped to organize military campaigns to reconquer once Christian lands in the East from the hands of the Muslims. Yet, even as an institution, the church was more than the papacy, more than its central government, which gained greater and greater control over the course of time. It was about new religious orders and persons like Benedict and Bernard and Francis of Assisi, and the countless numbers of men and women who followed them. Since records tend to be kept by and for great men, institutional history can understandably become the story of the great men − seldom women − popes and abbots rather than of parish priests and simple monks and nuns, or ordinary laymen and laywomen. It was a church whose fortunes can be charted, particularly at its higher reaches.

Yet a church without an essential spirituality is a body without a soul, form without substance, a hollow and empty contrivance. Nevertheless, the inner life of the church leaves less obvious, less certain traces than the institution. How deep was an individual’s commitment or what part prayer or contemplation played in one’s life or, indeed, how religious a person actually was it is difficult, nearly impossible to say. It is not given to the historian, mercifully, to be able to look into the souls of others, past or present, yet the historian must try, however diffidently, to examine the inner life of the church and try to get some sense of what religion really meant to Christian people. Inferences can be made from existing evidence such as acts of devotion and works of piety, where these can be seen, but one remains ever aware of the inherent difficulty in doing so.

The history of the church in a period extending over 1,000 years, with its continuities and changes, demands a healthy amount of caution and constraint. Generalizations about the Middle Ages must respect the variations and modalities of a long period of human history and of its different peoples and places. The expression ‘medieval church’ might be seen to imply a greater sameness than the historical record would permit. The ‘church in the Middle Ages’ allows us to regard the church in a historical period, during which it experienced profound changes. In this view, generalizations should not be made lightly and, when made, spoken only in the subjunctive mood. Caveat lector.

Floor plan of Christian basilica

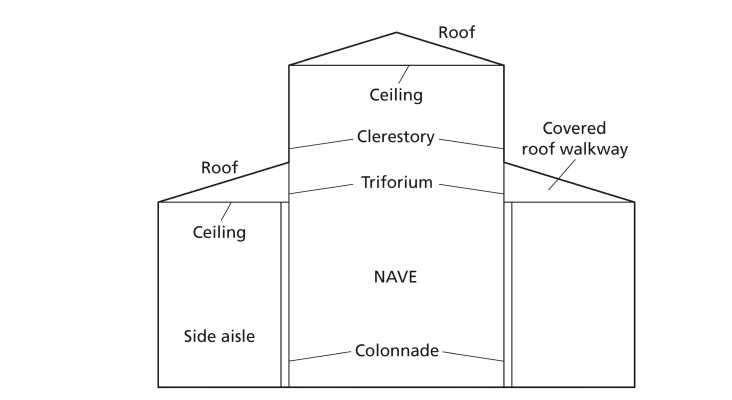

Cross-section of Christian basilica

List of Popes, 500-1500

A pope by definition is bishop of Rome. The date of the beginning of his pontificate is the date on which he became bishop of Rome. If the electee was already a bishop, he became bishop of Rome (and, thus, pope) at the time that he accepted election and not at the time of his subsequent coronation. If the electee was not a bishop, he became bishop of Rome (and, thus, pope) at the time of his consecration as bishop. It is this date that is preferred here. The pontificate ended with the death or, occasionally, with the resignation of the pope.

By convention some claimants are called anti-popes, where their claims have not been generally recognized by historians. Yet there will always be room for doubt. These anti-popes are listed in italics.

| Symmachus, 498-514 | ||

| Lawrence, 498-99; 501-06 | ||

| Hormisdas, 514-23 | ||

| John I, 523-26 | ||

| Felix IV (sometimes III), 526-30 | ||

| Dioscorus, 530 | ||

| Boniface II, 530-32 | ||

| John II, 533-35 | ||

| Agapitus I, 535-36 | ||

| Silverius, 536-37 | ||

| Vigilius, 537-55 | ||

| Pelagius I, 556-61 | ||

| John III, 561-74 | ||

| Benedict I, 575-79 | ||

| Pelagius II, 579-90 | ||

| Gregory I, 590-604 | ||

| Sabinian, 604-6 | ||

| Boniface III, 607 | ||

| Boniface IV, 608-15 | ||

| Deusdedit (also, Adeodatus I), 615-18 | ||

| Boniface V, 619-25 | ||

| Honorius I, 625-38 | ||

| Severinus, 640 | ||

| John IV, 640-42 | ||

| Theodore I, 642-49 | ||

| Martin I, 649-54 | ||

| Eugenius I, 654-57 | ||

| Vitalian, 657-72 | ||

| Adeodatus II, 672-76 | ||

| Donus, 676-78 | ||

| Agatho, 678-81 | ||

| Leo II, 682-83 | ||

| Benedict II, 684-85 | ||

| John V, 685-86 | ||

| Conon, 686-87 | ||

| Theodore, 687 | ||

| Paschal, 687 | ||

| Sergius I, 687-701 | ||

| John VI, 701-5 | ||

| John VII, 705-7 | ||

| Sisinnius, 708 | ||

| Constantine, 708-15 | ||

| Gregory II, 715-31 | ||

| Gregory III, 731-41 | ||

| Zacharias, 741-52 | ||

| Stephen II (sometimes III) 752-57 | ||

| Paul I, 757-67 | ||

| Constantine, 767—68 | ||

| Philip, 768 | ||

| Stephen III (sometimes IV), | ||

| 768-72 | ||

| Hadrian I, 772-95 | ||

| Leo III, 795-816 | ||

| Stephen IV (sometimes V), | ||

| 816-17 | ||

| Paschal I, 817-24 | ||

| Eugenius II, 824-27 | ||

| Valentine, 827 | ||

| Gregory IV, 828-44 | ||

| John, 844 | ||

| Sergius II, 844-47 | ||

| Leo IV, 847-55 | ||

| Benedict III, 855-58 | ||

| Anastasius, 855 | ||

| Nicholas I, 858-67 | ||

| Hadrian II, 867-72 | ||

| John VIII, 872-82 | ||

| Marinus I, 882-84 | ||

| Hadrian III, 884-85 | ||

| Stephen V (sometimes VI), 855-91 | ||

| Formosus, 891-96 | ||

| Boniface VI, 896 | ||

| Stephen VI (sometimes VII), 896-97 | ||

| Romanus, 897 | ||

| Theodore II, 897 | ||

| John IX, 898-900 | ||

| Benedict IV, 900-903 | ||

| Leo V, 903 | ||

| Christopher, 903—04 | ||

| Sergius III, 904-11 | ||

| Anastasius III, 911-13 | ||

| Lando, 913-14 | ||

| John X, 914-28 | ||

| Leo VI, 928 | ||

| Stephen VII (sometimes VIII), | ||

| 928-31 | ||

| John XI, 931-35 | ||

| Leo VII, 936-39 | ||

| Stephen VIII (sometimes IX), | ||

| 939-42 | ||

| Marinus II, 942-46 | ||

| Agapitus II, 946-55 | ||

| John XII, 955-64 | ||

| Leo VIII, 963-65 | ||

| Benedict V, 964 | ||

| John XIII, 965-72 | ||

| Benedict VI, 973-74 | ||

| Benedict VII, 974-83 | ||

| John XIV, 983-84 | ||

| Boniface VII, 974, 984-85 | ||

| John XV, 985-96 | ||

| Gregory V, 996-99 | ||

| John XVI, 997-98 | ||

| Sylvester II, 999-1003 | ||

| John XVII, 1003 | ||

| John XVIII, 1003-9 | ||

| Sergius IV, 1009-12 | ||

| Benedict VIII, 1012-24 | ||

| Gregory VI, 1012 | ||

| John XIX, 1024-32 | ||

| Benedict IX, 1032-44; 1045, ?1047-48 | ||

| Sylvester III, 1045 | ||

| Gregory VI, 1045-46 | ||

| Clement II, 1046-47 | ||

| Damasus II, 1048 | ||

| Leo IX, 1049-54 | ||

| Victor II, 1055-57 | ||

| Stephen IX (sometimes X), 1057-58 | ||

| Benedict X, 1058-59 | ||

| Nicholas II, 1058-61 | ||

| Alexander II, 1061-73 | ||

| Honorius II, 1061-64 | ||

| Gregory VII, 1073-85 | ||

| Clement III, 1080, 1084-1100 | ||

| Victor III, 1087 | ||

| Urban II, 1088-99 | ||

| Paschal II, 1099-1118 | ||

| Theodoric, 1100-01 | ||

| Albert, 1102 | ||

| Sylvester IV, 1105-11 | ||

| Gelasius II, 1118-19 | ||

| Gregory VIII, 1118-21 | ||

| Calixtus II, 1119-24 | ||

| Honorius II, 1124-30 | ||

| Celestine II, 1124 | ||

| Innocent II, 1130-43 | ||

| Anacletus II, 1130-38 | ||

| Victor IV, 1138 | ||

| Celestine II, 1143-44 | ||

| Lucius II, 1144-45 | ||

| Eugenius III, 1145-53 | ||

| Anastasius IV, 1153-54 | ||

| Hadrian IV, 1154-59 | ||

| Alexander III, 1159-81 | ||

| Victor IV, 1159-64 | ||

| Paschal TTT, 1164-68 | ||

| Calixtus TTT, 1168-78 | ||

| Innocent HI, 1179-80 | ||

| Lucius III, 1181-85 | ||

| Urban III, 1185-87 | ||

| Gregory VIII, 1187 | ||

| Clement III, 1187-91 | ||

| Celestine III, 1191-98 | ||

| Innocent III, 1198-1216 | ||

| Honorius III, 1216-27 | ||

| Gregory IX, 1227-41 | ||

| Celestine IV, 1241 | ||

| Innocent IV, 1243-54 | ||

| Alexander IV, 1254-61 | ||

| Urban IV, 1261-64 | ||

| Clement IV, 1265-68 | ||

| Gregory X, 1272-76 | ||

| Innocent V, 1276 | ||

| Hadrian V, 1276 | ||

| (never consecrated) | ||

| John XXI, 1276-77 | ||

| Nicholas III, 1277-80 | ||

| Martin IV, 1281-85 | ||

| Honorius IV, 1285-87 | ||

| Nicholas IV, 1288-92 | ||

| Celestine V, 1294 | ||

| Boniface VIII, 1295-1303 | ||

| Benedict XI, 1303-4 | ||

| Clement V, 1305-14 | ||

| John XXII, 1316-34 | ||

| Nicholas V, 1328-30 | ||

| Benedict XII, 1335-42 | ||

| Clement VI, 1342-52 | ||

| Innocent VI, 1352-62 | ||

| Urban V, 1362-70 | ||

| Gregory XI, 1371-78 | ||

| Rome | Avignon | Pisa |

|---|---|---|

| Urban VI (1378-89) | Clement VII (1378-94) | |

| Boniface IX (1389-1404) | Benedict XIII (1394-1423) | |

| Innocent VII (1404-06) | Alexander V (1409-10) | |

| Gregory XII (1406-15) | John XXIII (1410-15) | |

| Martin V, 1417-31 | ||

| Clement VIII, 1423-29 | ||

| Eugenius IV, 1431-47 | ||

| Felix V, 1439-49 | ||

| Nicholas V, 1447-55 | ||

| Calixtus III, 1455-58 | ||

| Pius II, 1458-64 | ||

| Paul II, 1464-71 | ||

| Sixtus IV, 1471-84 | ||

| Innocent VIII, 1484-92 | ||

| Alexander VI, 1492-1503 |