Chapter Contents

Chapter 1

Discussion Questions

- Discuss the ways in which the Ellis Island model, the transnational diasporic model and the racial constructivist model are useful in understanding the immigrant experience. In what ways are these models flawed? What kinds of ideologies (e.g. racial or political) present in the U.S. and elsewhere limit their ability to characterize the immigrant experience? How does the use of sociological models inform the study of immigrationhistory?

- The authors argued that the historical narrative of American immigration maintains a self-celebratory quality and that “filiopietistic motivations” dominate the study of immigration history. Do you agree with this assertion? If so, what does this tell us about the study of history? Should a scholar’s racial or ethnic identity be different than his or her subject of study? Is it possible to avoid subjectivity in research?

Notes

- Jacob Soboroff, Separated: Inside an American Tragedy (New York: HarperCollins, 2020); Laura Briggs, Taking Children: A History of American Terror (Oakland: University of California Press, 2020): 168-66; US Office of the Attorney General, “Memorandum for Federal Prosecutors along the Southwest Border: Zero-Tolerance for Offenses Under 8 U.S.C. § 1325(a)” (April 6, 2018); “Trump Migrant Separation Policy: Children ‘In Cages” in Texas” BBC (June 18, 2018); Ted Hesson and Lorraine Woellert, “DHS, HHS Officials Blindsided by ‘Zero Tolerance’ Border Policy,” Politico (October 24, 2018); Maria Sacchetti, “‘Kids in Cages’: House Hearing Examines Immigration Detention as Democrats Push for More Information,” Washington Post (July 10, 2019); “The Trump Child Abuse Scandal,” The Intercept (July 9, 2020); “Leading NGOs Call on ICE to Stop Family Separation,” Human Rights Watch (July 17, 2020).

- “Muslims Protest Border Check,” “U.S. Border Fingerprint Data Faulted,” and Johanna Neuman, “Canadian Cattle Cleared to Cross U.S. Border Again,” all in Los Angeles Times (December 30, 2004).

- Peter Kwong, Forbidden Workers: Illegal Chinese Immigrants and American Labor (New York: New Press, 1997), 1-10; Nancy Foner, From Ellis Island to JFK: New York’s Two Great Waves of Immigration (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2000), 17-18, 32-35; Patricia R. Pessar, A Visa for a Dream: Dominicans in the United States (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1995); Nina Bernstein, “Greener Pastures (on the Emerald Isle)” New York Times (November 10, 2004); Ellen Barry, “Survivors of a Sordid Venture Seek a Place,” Los Angeles Times (April 27, 2006).

- Nancy Abelmann and John Lie, Blue Dreams: Korean Americans and the Los Angeles Riots (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1995); Edward T. Chang and Russell C. Leong, eds., Los Angeles—Struggles Toward Multiethnic Community: Asian American, African American, and Latino Perspectives (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1994); Robert Gooding-Williams, ed., Reading Rodney King/Reading Urban Uprising (New York: Routledge, 1993).

- Benjamin Z. Zulueta, “ ‘Brains at a Bargain’: Refugee Chinese Intellectuals, American Science, and the ‘Cold War of the Classrooms’ ” (Ph.D. diss., University of California, Santa Barbara, 2003): 63-67; Iris Chang, Thread of the Silkworm (New York: Basic Books, 1995); William L. Ryan and Sam Summerlin, The China Cloud: America’s Tragic Blunder and China’s Rise to Nuclear Power (Boston, Little, Brown, 1968).

- Fernando Saúl Alanís Enciso, They Should Stay There: The Story of Mexican Migration and Repatriation during the Great Depression, trans. Ross Davidson (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017); Francisco E. Balderrama and Raymond Rodríguez, Decade of Betrayal: Mexican Repatriation in the 1930s (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1995); R. Reynolds McKay, “Texas Mexican Repatriation During the Great Depression,” (Ph.D. diss., University of Oklahoma, 1982); Rodolfo Acuña, Occupied America: A History of Chicanos, 3rd ed. (New York: Harper and Row, 1988), 200-06; Barbara M. Posadas, The Filipino Americans (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood, 1999), 23-24.

- Roger Daniels, Guarding the Golden Door: American Immigration Policy and Immigrants since 1882 (New York: Hill and Wang, in press; 2004), 27-58; Roger Daniels, Coming to America: A History of Immigration and Ethnicity in American Life, 2nd ed. (New York: Harper Collins, 2002), 282-84; Daniel Okrent, The Guarded Gate (New York: Scribner, 2019).

- Jia Lynn Yang, “Overlooked No More: Mabel Ping-Hua Lee, Suffragist With a Distinction,” New York Times (September 19, 2020).

- Francis Paul Prucha, The Great Father: The United States Government and the American Indians, abr. ed. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1986), 221; H. Henrietta Stockel, Survival of the Spirit: Chiricahua Apaches in Captivity (Reno: University of Nevada Press, 1993); Edward H. Spicer, Cycles of Conquest: The Impact of Spain, Mexico, and the United States on the Indians of the Southwest, 1533-1960 (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1962), 229-61; Keith A. Murray, The Modocs and Their War (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1959); Kinglsey M. Bray, “Crazy Horse and the End of the Great Sioux War,” Nebraska History, 79 (1998), 96-115; Peter Nabokov, ed., Native American Testimony, rev. ed. (New York: Penguin, 1999), 178-81.

- Moses Rischin, The Promised City: New York’s Jews (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1962); Irving Howe, World of Our Fathers: The Journey of the East European Jews to America and the Life They Found and Made (New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, 1976).

- Gordon H. Chang, Ghosts of Gold Mountain: The Epic Story of the Chinese Who Built the Transcontinental Railroad (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2019); Gordon H. Chang and Shelley Fisher Fishkin, eds., The Chinese and the Iron Road: Building the Transcontinental Railroad (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2019); Manu Karuka, Empire’s Tracks: Indigenous Nations, Chinese Workers, and the Transcontinental Railroad (Oakland: University of California Press, 2019); David E. Miller, ed., The Golden Spike (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1973); David Howard Bain, Empire Express: Building the First Transcontinental Railroad (New York: Viking, 1999); Stephen E. Ambrose, Nothing Like It in the World: The Men Who Built the Transcontinental Railroad, 1863-1869 (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2000).

- Richard Griswold del Castillo, The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo: A Legacy of Conflict (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1990); Martha Menchaca, Recovering History, Constructing Race: The Indian, Black, and White Roots of Mexican Americans (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2001): 215-76; Leonard Pitt, The Decline of the Californios: A Social History of the Spanish-speaking Californians, 1846-1890 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1962); Albert Camarillo, Chicanos in a Changing Society: From Mexican Pueblos to American Barrios in Santa Barbara and Southern California, 1848-1930 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1979); Andrés Reséndez, Changing National Identities at the Frontier: Texas and New Mexico, 1800-1850 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2005); David Torres-Rouff, Before LA: Race, Space, and Municipal Power, 1781-1894 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2013).

- Kerby A. Miller, Emigrants and Exiles: Ireland and the Irish Exocus to North America (New York: Oxford, 1985), 3, 281-344, 569; US Census Bureau, “Irish-American Heritage Month (March) and St. Patrick’s Day (March 17)” (http:www.census.gov/Press-Release/www/archives/facts_for_features/001687.html, November 11, 2004).

- Theda Perdue and Michael D. Green, eds., The Cherokee Removal (Boston: Bedford Books, 1995); Grant Foreman, Indian Removal: The Emigration of the Five Civilized Tribes of Indians (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1953); William L. Anderson, ed., Cherokee Removal: Before and After (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1991); Gregory D. Smithers, The Cherokee Diaspora: An Indigenous History of Migration, Resettlement, and Identity (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015).

- Bernard Bailyn, Voyagers to the West: A Passage in the Peopling of America on the Eve of the Revolution (New York: Knopf, 1986).

- Daniel J. Weber, What Caused the Pueblo Revolt of 1680? (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 1999); Andrew L. Knaut, The Pueblo Revolt of 1680: Conquest and Resistance in Seventeenth-Century New Mexico (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1995).

- Winthrop D. Jordan, The White Man’s Burden: Historical Origins of Racism in the United States (New York: Oxford, 1974), 26-54; Edmund S. Morgan, American Slavery, American Freedom (New York: Norton, 1975); Alden T. Vaughan, “The Origins Debate: Slavery and Racism in Seventeenth-Century Virginia,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 97.3 (1989), 311ff; Darlene Clark Hine, William C. Hine, and Stanley Harrold, The African-American Odyssey, 2nd ed. (Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Prentice Hall, 2003), 51-54; Kathleen M. Brown, Good Wives, Nasty Wenches, and Anxious Patriarchs: Gender, Race, and Power in Colonial Virginia (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996): 107-36.

- William Bradford, Of Plymouth Plantation (New York: Knopf, 1952); Francis J. Bremer, The Puritan Experiment (New York: St. Martin’s, 1976); Alden T. Vaughan, New England Frontier: Puritans and Indians, 1620-1675, rev. ed. (New York: Norton, 1979).

- An outline of this argument appeared in “Asian Americans, Religion, and Race,” in Borders, Boundaries, and Bonds: America and Its Immigrants in Eras of Globalization, ed. Elliott Barkan, Hasia Diner, and Alan Kraut (New York: NYU Press, 2007): 94-117.

- J. Hector St. John de Crèvecoeur, Letters from an American Farmer (London, 1782), reproduced in Moses Rischin, ed., Immigration and the American Tradition (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1976), 25-26. The power of such self-congratulatory rhetoric persists over the centuries. Whitewater prosecutor and Clinton tormentor Ken Starr wrote in his 2002 Christmas letter to family and friends: “Proudly, this nation, hewn from the vast frontier by those great generations who went before us, stands strong. . . . the land of the free and home of the brave. . . . We shall prevail. With apologies to no one, we already are prevailing. . . . Americans come from sturdy stock. We gave the world a new birth in freedom, whereas those our forebears left behind in Europe gave us Nazism, Fascism and Communism. (Take note, England is a brave and bold exception to this hothouse of political pathologies.)” “Sincerely, Ken Starr,” Newsweek (February 10, 2003).

- Carl Wittke, We Who Built America: The Saga of the Immigrant (New York: Prentice-Hall, 1940). Louis Adamic projected a similarly celebratory attitude toward immigrants—all of them European and none of them English —in A Nation of Nations (New York: Harper, 1945).

- Milton M. Gordon, Assimilation in American Life (New York: Oxford, 1964).

- Peter Brimelow, Alien Nation: Common Sense about America’s Immigration Disaster (New York: Random House, 1995), xvii, xxi, 18-19. Brimelowʻs arguments are echoed by another hard-right, but highly articulate xenophobe, Mark Krikorian, in The New Case Against Immigration: Both Legal and Illegal (New York: Penguin, 2008).

- I wish no disrespect of either the late Professor Handlin or Professor Bodnar, I am very much aware of each man’s contribution, and I am personally grateful to Professor Handlin for giving me my first research grant while I was still an undergraduate. But there is a blindness in their approaches. The Uprooted, 2nd ed. (Boston: Little, Brown, 1973), 3; Oscar Handlin, ed., Immigration as a Factor in American History (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1959); John Bodnar, The Transplanted: A History of Immigrants in Urban America (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1985). An otherwise outstanding collection of documents by eminent historian Jon Gjerde continues the erasure of the immigrant quality of Anglo-Americans; Major Problems in American Immigration and Ethnic History (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1998).

- Emma Lazarus, “The New Colossus,” quoted in Alan M. Kraut, The Huddled Masses: The Immigrant in American Society, 1880-1921, 2nd ed. (Wheeling, Ill.: Harlan Davidson, 2001), 2. For trenchant critique of this paradigm, see Kevin R. Johnson, The “Huddled Masses” Myth: US Immigration Law and Civil Rights (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2004).

- I am grateful to Patrick B. Miller for this phrase.

- John Quincy Adams, to Baron Morris von Furstenwäther, June 4, 1819, reproduced in Rischin, Immigration and the American Tradition: 44-49.

- Wittke, We Who Built America.

- The same pattern is followed by Maldwyn Allen Jones, American Immigration (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1960); Thomas J. Archdeacon, Becoming Americans: An Ethnic History (New York: Free Press, 1983); Reed Ueda, Postwar Immigrant America: A Social History (Boston: Bedford Books, 1994); Leonard Dinnerstein and David M. Reimers, Ethnic Americans: A History of Immigration, 4th ed. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999); Robert L. Fleegler, Eillis Island Nation: Immigration Policy and American Identity in the Twentieth Century (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013). Roger Daniels began to make a conceptual shift in Coming to America: A History of Immigration and Ethnicity in American Life, 2nd ed. (New York: Harper Collins, 2002).

- Thomas Muller and Thomas J. Espenshade, The Fourth Wave: California’s Newest Immigrants (Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute Press, 1985).

- Richard Alba and Victor Nee, Remaking the American Mainstream: Assimilation and Contemporary Immigration (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2003): ix. See also Alba and Nee, “Rethinking Assimilation Theory for a New Era of Immigration,” International Migration Review, 31.4 (1997), 826-74; Richard D. Alba, Italian Americans: Into the Twilight of Ethnicity (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Prentice-Hall, 1985); R. Stephen Warner and Judith G. Wittner, eds., Gatherings in Diaspora: Religious Communities and the New Immigration (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1998), 14-15 and passim; Russell A. Kazal, “Revisiting Assimilation: The Rise, Fall, and Reappraisal of a Concept in American Ethnic History,” American Historical Review (April 1995), 437-71.

- Lori Pierce refers to this as “The Eck Effect: The Racial Conundrum of Religious Diversity” in a paper given at Lake Forest College to the Second Annual Parliament of the World’s Sacred Traditions (Lake Forest, Ill., September 21, 2003). Cf. Diana L. Eck, A New Religious America: How a “Christian Country” Has Now Become the World’s Most Religiously Diverse Nation (New York: Harper Collins, 2001).

- That is explicitly the contention of Alba and Nee, Remaking the American Mainstream.

- Paul Spickard, “It’s the World’s History: Decolonizing Historiography and the History of Christianity,” Fides et Historia, 32.2 (summer/fall 2000), 13-29.

- Diane Johnson, “False Promises,” New York Review of Books (December 4, 2003): 4.

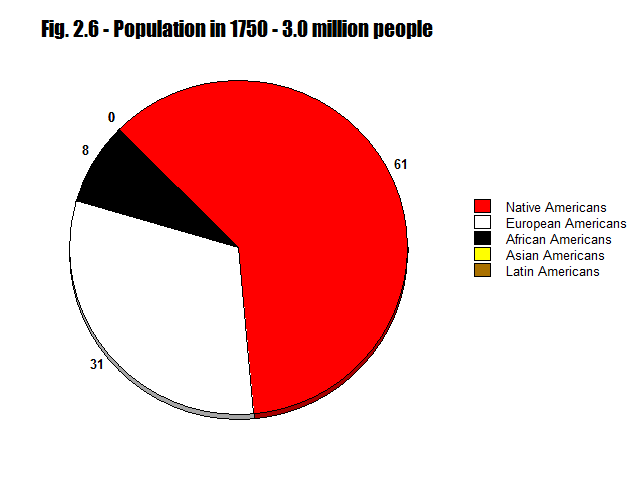

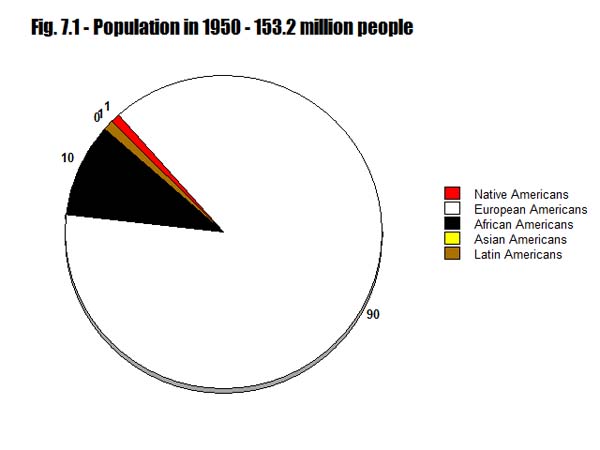

- See Chapter 2, Table 2.1, and Appendix, Table 9.

- Gary B. Nash, Red, White, and Black: The Peoples of Early America (Englewood Cliff, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1974); Juliana Barr, Peace Came in the Form of a Woman: Indians and Spanish in the Texas Borderlands (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007); Michael A. Gomez, Exchanging Our Country Marks: The Transformation of African Identities in the Colonial and Antebellum South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998); Theda Perdue, “Mixed-Blood” Indians: Racial Construction in the Early South (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2003); Tomás Almaguer, Racial Fault Lines: The Historical Origins of White Supremacy in California (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994); Albert Camarillo, Chicanos in a Changing Society (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1979); Neil Foley, The White Scourge: Mexicans, Blacks, and Poor Whites in Texas Cotton Culture (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997); Menchaca, Recovering History, Constructing Race; Torres-Rouff, Before LA; H. Craig Miner and William E. Unrau, The End of Indian Kansas: A Study of Cultural Revolution, 1854-1871 (Laurence, Kans.: Regents Press, 1978); Murray R. Wickett, Contested Territory: Whites, Native Americans, and African Americans in Oklahoma, 1865-1907 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2000); William Loren Katz, Black Indians (New York: Atheneum, 1986); Jack D. Forbes, Africans and Native Americans: The Language of Race and the Evolution of Red-Black Peoples, 2nd ed. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993); James F. Brooks, ed., Confounding the Color Line: The Indian-Black Experience in North America (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2002); Arnoldo DeLeon, Racial Frontiers: Africans, Chinese, and Mexicans in Western America, 1848-1890 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2002); Quintard Taylor, The Forging of a Black Community: Seattle’s Central District, from 1870 through the Civil Rights Era (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1994); Jacalyn D. Harden, Double Cross: Japanese Americans in Black and White Chicago (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003); Samuel Truett, Fugitive Landscapes: The Forgotten History of the US-Mexico Borderlands (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2006); Samuel Truett and Elliott Young, eds., Continental Crossroads: Remapping US-Mexico Borderlands History (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004); Nayan Shah, Stranger Intimacy: Contesting Race, Sexuality, and the Law in the North American West (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011).

- Will Herberg, Protestant, Catholic, Jew, rev. ed. (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1960), 42.

- Richard D. Alba and Albert Raboteau, eds., Religion, Immigration, and Civic Life in Historical Comparative Perspective (New York: Social Science Research Council and Russell Sage Foundation, in press); I am a contributor to this volume and appreciate the editors’ scholarship and friendship, even as I disagree thoroughly with the way they frame this issue. Michael Barone makes a similar interpretive move to Alba and Raboteau’s, for reasons that strike me as less innocent, in The New Americans: How the Melting Pot Can Work Again (Washington: Regnery, 2001).

- Gomez, Exchanging Our Country Marks; Michael A. Gomez, Diasporic Africa: A Reader (New York: New York University Press, 2006); Gwendolyn Midlo Hall, Slavery and African Ethnicities in the Americas: Restoring the Links (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005); Gwendolyn Midlo Hall, Africans in Colonial Louisiana: The Development of Afro-Creole Culture in the Eighteenth Century (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1992).

- Ellis Island Immigration Museum exhibit, “The Peopling of America,” October 28, 2003. The figures were compiled by Russell Menard and Henry A. Gemery. See Chapter 2, Table 2.1.

- For related issues, see Philip J. Deloria, Playing Indian (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1998).

- Vine Deloria, Jr., Custer Died for Your Sins (New York: Avon, 1969).

- Deloria, Playing Indian, 5, 7. See also Carter Jones Meyer and Diana Royer, eds., Selling the Indian: Commercializing and Appropriating American Indian Cultures (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2001); Liza Black, Picturing Indians: Native Americans in Film, 1941-1960 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2020).

- Dances with Wolves, dir. Kevin Costner (Los Angeles: Orion Pictures, 1990).

- David Montejano, Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas, 1836-1986 (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1987); Almaguer, Racial Fault Lines; Foley, The White Scourge; Menchaca, Recovering History, Constructing Race; David J. Weber, ed., Foreigners in their Native Land: Historical Roots of the Mexican Americans (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1973).

- Roger Rouse, “Mexican Migration and the Social Space of Postmodernism,” Diaspora, 1.1 (1991).

- Appendix, Table 16; Roger Daniels, Coming to America: A History of Immigration and Ethnicity in American Life (New York: Harper Collins, 1990), 184.

- Lisa Lowe, Immigrant Acts: On Asian American Cultural Politics (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1996): 6; Mia Tuan, Forever Foreigners or Honorary Whites? The Asian Ethnic Experience Today (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1998); David J. Weber, Foreigners in Their Native Land: Historical Roots of the Mexican Americans (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1973).

- Paul Spickard worked in Locke’s campaign.

- Paul Spickard and W. Jeffrey Burroughs, eds., We Are a People: Narrative and Multiplicity in Constructing Ethnic Identity (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2000); Paul Spickard and G. Reginald Daniel, eds., Racial Thinking in the United States: Uncompleted Independence (Notre Dame, Ind.: University of Notre Dame Press, 2004); Michael Omi and Howard Winant, Racial Formation in the United States: From the 1960s to the 1990s (New York: Routledge, 1994); Yen Le Espiritu, Asian American Panethnicity (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1992); G. Reginald Daniel, More Than Black? Multiracial Identity and the New Racial Order (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2002); David Roediger, The Wages of Whiteness: Race and the Making of the American Working Class (London: Verso, 1991).

- Ralph Waldo Emerson, Journal, quoted in Milton M. Gordon, Assimilation in American Life (New York: Oxford, 1964), 117.

- Israel Zangwill, The Melting Pot (New York: Macmillan, 1909): 37, quoted in Gordon, Assimilation in American Life: 120.

- The New Face of America: How Immigrants Are Shaping the World’s First Multicultural Society, a special issue of Time, 142.21 (Fall 1993).

- Gordon, Assimilation in American Life: 84-114.

- Herberg, Protestant, Catholic, Jew, 33-34. The term “transmuting pot” belongs to George R. Stewart, American Ways of Life (New York: Doubleday, 1954), 23.

- We understand this to be Michael Barone’s intent expressed in the subtitle of The New Americans: How the Melting Pot Can Work Again.

- Gordon, Assimilation in American Life, 76 and passim.

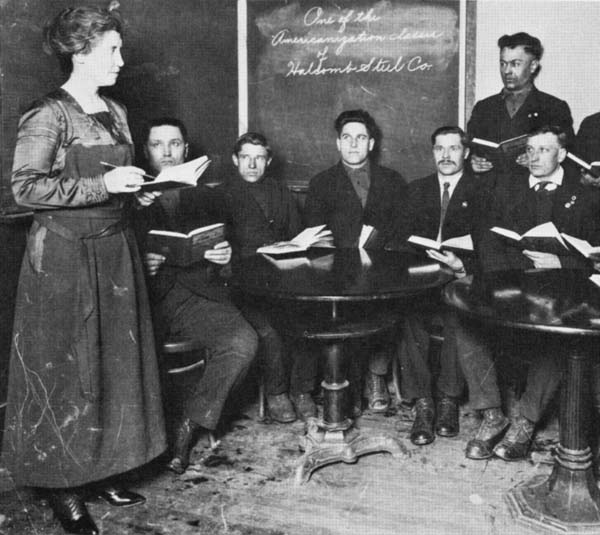

- Eileen Tamura, Americanization, Acculturation, and Ethnic Identity: The Nisei Generation in Hawai‘i (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1994).

- Richard Alba, Italian Americans: Into the Twilight of Ethnicity (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1984); David A. Hollinger, Postethnic America: Beyond Multiculturalism (New York: Harper Collins, 1995). Several scholars have modified the crude assimilation model, putting forth the idea of “segmented assimilation”—not becoming undifferentiated Americans, but adjusting by adopting the mores of one of a variety of immigrant enclaves. See three books by Alejandro Portes and Rubén Rumbaut: Immigrant America, 2nd ed. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996); Legacies: The Story of the Immigrant Second Generation (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001); and as editors, Ethnicities: Children of Immigrants in America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001).

- George Yancey makes that explicit claim in Who is White? Latinos, Asians, and the New Black/Nonblack Divide (Boulder, Colo.: Lynne Rienner, 2003), 9-10: “Latino and Asian Americans are beginning to approach racial issues from a majority group perspective. . . . they are on their way to becoming ‘white’.” Richard Alba and Victor Nee, recognizing that Chinese people are not likely to become quite White, but insisting nonetheless that they will have the same status as Whites, make a more muted claim: “[A]ssimilation is not likely to require that non-Europeans come to view themselves as ‘whites’. . . . multiculturalism may already be preparing the way for a redefinition of the nature of the American social majority, one that accepts a majority that is racially diverse.” Remaking the American Mainstream, 288-89; Eduardo Bonilla-Silva is equally mistaken, if slightly more subtle, in proclaiming some Asian Americans to be “Honorary Whites” and others part of the “Collective Black” in “We Are All Americans! The Latin Americanization of Racial Stratification in the USA,” Race and Society, 5 (2002): 3-16.

- Matthew Frye Jacobson, Whiteness of a Different Color: European Immigrants and the Alchemy of Race (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1998).

- Paul Spickard, “Who Is an American? Teaching about Racial and Ethnic Hierarchy,” Immigration and Ethnic History Newsletter, 31.1 (May 1999).

- Some of the material in this section derives from my introduction to Pacific Diaspora: Island Peoples in the United States and Across the Pacific, which I edited with Joanne L. Rondilla and Debbie Hippolite Wright (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2003), 1-27.

- Margot Johnson, "Washington Old Hall" in Durham: Historic and University City and Surrounding Area., 6th ed. (Durham, UK: Turnstone Ventures, 1992): 40; Ron Chernow, Washington: A Life (New York: Penguin, 2010); George Goodwin, Benjamin Franklin in London: The British Life of Americaʻs Founding Father (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2016).

- James Clifford, “Diasporas,” Cultural Anthropology, 9.3 (1994); Roger Rouse, “Mexican Migration and the Social Space of Postmodernism,” Diaspora, 1.1 (1991); Robin Cohen, Global Diasporas (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1997). On the Italian, British, and Greek diasporas, see, for example: Gloria La Cava, Italians in Brazil (New York: Peter Lang, 1999); Arnd Schneider, Futures Lost: Nostalgia and Identity among Italians in Argentina (New York: Peter Lang, 2000); Samuel L. Baily, Immigrants in the Lands of Promise: Italians in Buenos Aires and New York City, 1870-1914 (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2003); Carl Bridge and Kent Federowich, eds., The British World: Diaspora, Culture, and Identity (London: Frank Cass, 2003); Tony Simpson, The Immigrants: The Great Migration from Britain to New Zealand, 1830-1880 (Auckland: Godwit, 1997); Lawrence James, Raj: The Making and Unmaking of British India (Griffin, 2000); C. J. Hawes, Poor Relations: The Making of a Eurasian Community in British India, 1773-1833 (New York: Curzon, 1996); Theodore Saloutos, They Remember America: The Story of the Repatriated Greek-Americans (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1956).

- Rouse, “Mexican Migration,” 13.

- Truett, Fujitive Landscapes; Menchaca, Recovering History, Constructing Race.

- Xiaojian Zhao, Remaking Chinese America: Immigration, Family, and Community, 1940-1965 (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2002); Adam McKeown, “Conceptualizing Chinese Diasporas,” Journal of Asian Studies, 58 (1999), 306-37; Adam McKeown, Chinese Migrant Networks and Cultural Change (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001). The literature on diasporas is growing rapidly. See, for example, Vijay Mishra, “The Diasporic Imaginary: Theorizing the Indian Diaspora,” Textual Practice, 10.3 (1996): 421-47; Cohen, Global Diasporas; Gerard Chaliand, et al., The Penguin Atlas of Diasporas (New York: Penguin, 1997); Nicholas Van Hear, New Diasporas: The Mass Exodus, Dispersal, and Regrouping of Migrant Communities (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1998); Darshan Singh Tatla, The Sikh Diaspora (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1999); Michael A. Gomez, Reversing Sail: A History of the African Diaspora, 2nd ed. (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2020); Kevin Kenny, Diaspora: A Very Short Introduction (New York: Oxford University Ppress, 2013).

- I recognize that some would draw distinctions between these terms, and even between “diaspora” and “diasporic,” but I will treat them as roughly synonymous.

- Sau-ling C. Wong, “Denationalization Reconsidered: Asian American Cultural Criticism at a Theoretical Crossroads,” Amerasia Journal 21.1 and 21.2 (1995), 14-15. Elliott Barkan makes the gentler criticism that the nation-state was not the focus of most immigrants’ identities. He calls them “translocal” rather than “transnational” in “America in the Hand, Homeland in the Heart: Transnational and Translocal Experiences in the American West,” Western Historical Quarterly, 35.3. Since Professor Wong’s germinal essay was published in 1995, a number of scholars have taken up her challenge and have written deeply insightful transnational studies that avoid the pitfalls she points out. Among them are Eiichiro Azuma, In Search of Our Frontier: Japanese America and Settler Colonialism in the Construction of Japan’s Borderless Empire (Oakland: University of California Press, 2019); Simeon Man, Soldiering Through Empire: Race and the Making of the Decolonizing Pacific (Oakland: University of California Press, 2018); Susie Woo, Framed by War: Korean Children and Women at the Crossroads of US Empire (New York: New York University Press, 2019).

- Paul Mecheril and Thomas Teo, Andere Deutsche [Other Germans](Berlin: Dietz Verlag, 1994); Craig S. Smith, “French-Born Arabs Perpetually Foreign, Grow Bitter,” New York Times (December 26, 2003); Elisabeth Schäfer-Wünsche, “On Becoming German: Politics of Membership in Germany,” in Race and Nation: Ethnic Systems in the Modern World, ed. Paul Spickard (New York: Routledge, 2005), 195-211; David Horrocks and Eva Kolinsky, eds., Turkish Culture in Germany Today (Providence, R.I.: Berghahn, 1996); Paul Spickard, ed., Multiple Identities: Migrants Ethnicity, and Membership (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013); Theo Sarrazin, Deutschland schaft sich ab [Germany Abolishes Itself] (Munich: Deutsche Verlags-Anhalt, 2010); Jay Julian Rosellini, The New German Right: AFD, PEGIDA, and the Re-Imagining of National Identity (London: Hurst and Company, 2019); Allan Pred, Even in Sweden: Racisms, Racialized Spaces, and the Popular Geographical Imagination (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000); Paul A. Silverstein, Algeria in France: Transpolitics, Race, and Nation (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2004).

- Roger Daniels uses this mode of analysis in Coming to America, as does Sucheng Chan in Asian Americans: An Interpretive History (Boston: Twayne, 1991).

- Edna Bonacich and Lucie Cheng, “A Theoretical Orientation to International Labor Migration,” in Labor Immigration Under Capitalism: Asian Workers in the United States before World War II, ed. Cheng and Bonacich (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984): 1-56. See also L. S. Stavrianos, Global Rift: The Third World Comes of Age (New York: Morrow, 1981); Walter Rodney, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, rev. ed. (Washington: Howard University Press, 1981).

- Alba and Nee, Remaking the American Mainstream: ix.

- Yen Le Espiritu, Asian American Panethnicity (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1992). For a theoretical view of this and related processes, see Paul Spickard and W. Jeffrey Burroughs, “We Are a People,” in We Are a People: Narrative and Multiplicity in Constructing Ethnic Identity, ed. Spickard and Burroughs (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2000), 1-19. On White racial formation, see Jacobson, Whiteness of a Different Color; Paul Spickard, “What’s Critical About White Studies?” in Racial Thinking in the United States, ed. Spickard and Daniel, 248-74; Charles H Anderson, White Protestant Americans (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1970). On Latina/o racial formation, see Laura E. Gómez, Inventing Latinos (New York: New Press, 2020); Martha Menchaca, Recovering History, Constructing Race: The Indian, Black, and White Roots of Mexican Americans (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2002).

- The senior author of this volume has laid out his thinking on race and ethnicity more fully in Race and Nation and Race in Mind: Critical Essays (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2015). This section is drawn from those sources. The reader will benefit from two works by Stephen Cornell and Douglas Hartmann: Ethnicity and Race: Making Identities in a Changing World (Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Pine Forge Press, 1998) and “Conceptual Confusions and Divides: Race, Ethnicity, and the Study of Immigration,” in Not Just Black and White: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives on Immigration, Race, and Ethnicity in the United States, ed. George Fredrickson and Nancy Foner (New York: Russell Sage, 2004), 23-41.

- Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, The Anthropological Treatises of Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (Boston: Milford House, 1973; orig. 1865); Joseph Arthur, comte de Gobineau, The Inequality of Races (New York: H. Fertig, 1915; orig. 1856); Francis Galton, Essays in Eugenics (Honolulu: University Press of the Pacific, 2004; orig. 1909); Earnest Hooton, Apes, Men, and Morons (New York: Putnam's, 1937); Carleton S. Coon, The Origin of Races (New York: Knopf, 1962); J. Philippe Rushton, Race, Evolution, and Behavior, 3rd ed. (Port Huron, Mich.: Charles Darwin Research Institute, 2000); Richard J. Herrnstein and Charles Murray, The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life (New York: Free Press, 1994); John Entine, Taboo: Why Black Athletes Dominate Sports and Why We’re Afraid to Talk About It (New York: Public Affairs, 2000); Nicholas Wade, A Troublesome Inheritance: Genes, Race and Human History (New York: Penguin, 2015); Emmanuel Chukwudi Eze, ed., Race and the Enlightenment (Oxford: Blackwell, 1997). Scholars such as Dinesh D’Souza and Thomas Sowell essentialize “culture” and use it to the same ends as the pseudo-scientists use “race”; see D’Souza, The End of Racism: Principles for a Multiracial Society (New York: Free Press, 1995); Sowell, Ethnic America (New York: Basic Books, 1981).

- For correctives, see Jonathan Marks, Human Biodiversity: Genes, Race, and History (New York: Aldine de Gruyter, 1995); Marks, What It Means to be 98% Chimpanzee: Apes, People, and Their Genes (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002); William H. Tucker, The Science and Politics of Racial Research (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1994); Steven Fraser, ed., The Bell Curve Wars: Race, Intelligence, and the Future of America (New York: Basic Books, 1995); Stephen Jay Gould, The Mismeasure of Man, rev. ed. (New York: Norton, 1996); Patrick B. Miller, “The Anatomy of Scientific Racism: Racialist Responses to Black Athletic Achievement,” in We Are a People, ed. Spickard and Burroughs, 124-41; Joseph L. Graves, Jr., The Emperor’s New Clothes: Biological Theories of Race at the Millennium (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2001); Matt Ridley, Nature via Nurture: Genes, Experience, and What Makes Us Human (New York: Harper Collins, 2003); Robert Wald Sussman, The Myth of Race: The Troubling Persistence of an Unscientific Idea (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014); Angela Saini, Superior: The Return of Race Science (Boston: Beacon Press, 2020); Terence Keel, Divine Variations: How Christian Thought Became Racial Science (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2019).

- See, for example, the pseudoscientific racialists in footnote 77, plus Madison Grant, The Passing of the Great Race; or, The Racial Basis of European History (New York: Scribnerʻs, 1916); Lothrop Stoddard, The Rising Ride of Color Against White World-Supremacy (New York: Scribnerʻs, 1920).

- See, for example, the correctives noted in footnote 77, as well as Paul Spickard, “The Illogic of American Racial Categories,” in Racially Mixed People in America, ed. Maria P. P. Root (Newbury Park, Calif.: Sage, 1992), 12-23; Spickard and Burroughs, “We Are a People”; Miri Song, Choosing Ethnic Identity (Cambridge, U.K.: Polity Press, 2003); Michael Omi and Howard Winant, Racial Formation in the United States, rev. ed. (New York: Routledge, 1994); Stephen Cornell and Douglas Hartmann, Ethnicity and Race (Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Pine Forge Press, 1998).

- Reginald Horsman, Race and Manifest Destiny: The Origins of American Racial Anglo-Saxonism (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1981); Matthew Frye Jacobson, Special Sorrows: The Diasporic Imaginations of Irish, Polish, and Jewish Immigrants in the United States, rev. ed. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002): 177-216; Catherine Hall, ed., Cultures of Empire: Colonizers in Britain and the Empire in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries (New York: Routledge, 2000); see also Robert J. C. Young, Colonial Desire: Hybridity in Theory, Culture and Race (London: Routledge, 1995).

- Spickard and Burroughs, “We Are a People,” 2-7.

- Of course there are meaningful differences between peoples within each of the US races, as well. Korean Americans and Vietnamese Americans are quite different from one another—much more so than are, say, Irish Americans and Italian Americans. For a critique of the intellectual and political movement that would elevate differences among White people of different ethnic derivations to something like the level of racial differences, see Spickard, “What’s Critical About White Studies.”

- Small, Racialised Barriers; Anthias and Yuval-Davis, Racialized Boundaries; Paul Spickard, “Mapping Race: Multiracial People and Racial Category Construction in the United States and Britain,” Immigrants and Minorities, 15 (July 1996), 107-19; Tomás Almaguer, Racial Fault Lines: The Historical Origins of White Supremacy in California (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994).

- Taoufik Djebali, “Ethnicity and Power in North Africa (Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco)” in Race and Nation, ed. Spickard, 135-54; Rowena Fong and Paul Spickard, “Ethnic Relations in the People’s Republic of China,” Journal of Northeast Asian Studies13.1 (Spring 1994): 26-48; Christine Su, “Becoming Cambodian: Ethnicity and the Vietnamese in Kampuchea,” in Race and Nation, ed. Spickard, 273-97.

- Virginia Tilley, “Mestizaje and the ‘Ethnicization’ of Race in Latin America,” in Race and Nation, ed. Spickard, 53-68; Paul Spickard, Race in Mind: Critical Essays (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2015).

- F. James Davis, Who Is Black? One Nation’s Definition (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1991); G. Reginald Daniel, “Passers and Pluralists: Subverting the Racial Divide,” in Racially Mixed People in America, ed. Root, 91-107; Ingrid Dineen-Wimberly, The Allure of Blackness among Mixed-Race Americans (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2019).

- Lily Anne Y. Welty Tamai, Ingrid Dineen-Wimberly, and Paul Spickard, eds., Shape Shifters: Journeys across Terrains of Race and Identity (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2020); Circe Sturm, Blood Politics: Race, Culture, and Identity in the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002); James F. Brooks, ed., Confounding the Color Line: The Indian-Black Experience in North America (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2002); Teresa Williams-León and Cynthia Nakashima, eds., The Sum of Our Parts: Mixed Heritage Asian Americans (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2001); Paul Spickard, “What Must I Be? Asian Americans and the Question of Multiethnic Identity,” Amerasia Journal, 23.1 (Spring 1997), 43-60.

- Much of the section that follows from Paul Spickard and W. Jeffrey Burroughs, “We Are a People”.

- This conceptual division of ethnicity into essentially three different kinds of processes with three different kinds of ethnic glue is the brainchild or Stephen Cornell; see his article, “The Variable Ties That Bind: Content and Circumstance in Ethnic Processes,” Ethnic and Racial Studies (1996); also Cornell and Hartmann, Ethnicity and Race.

- Abner Cohen, “The Lesson of Ethnicity,” in Cohen, ed., Urban Ethnicity (London: Tavistock, 1974), ix-xxiv; June Teufel Dreyer, China’s Forty Millions: Minority Nationalities and National Integration (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1976); Guibernau and Rex, Ethnicity Reader; Nathan Glazer and Daniel P. Moynihan, Beyond the Melting Pot (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1963); William Kornblum, Blue Collar Community (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1974); Joseph Rothschild, Ethnopolitics (New York: Columbia University Press, 1981); William Julius Wilson, The Declining Significance of Race, 2nd ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980).

- Alejandro Portes, “‘Hispanic’ Proves to Be a False Term,” Chicago Tribune (November 2, 1989).

- Alba, Italian Americans; Gordon, Assimilation; William Yancey, et al., “Emergent Ethnicity,” American Sociological Review, 41 (1976), 391-403.

- Timothy P. Fong, The First Suburban Chinatown: The Remaking of Monterey Park, California (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1994).

- Park, Race and Culture; E. Franklin Frazier, Race and Culture Contacts in the Modern World (New York: Knopf, 1957); Stephen Steinberg, The Ethnic Myth (Boston: Beacon Press, 1981); Edward Said, Culture and Imperialism (New York: Random House, 1993).

- L. Epstein, Ethos and Identity (London: Tavistock, 1978); Mary C. Waters, Black Identities: West Indian Immigrant Dreams and American Realities (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001); Marilyn Halter, Shopping for Identity: The Marketing of Ethnicity (New York: Schocken, 2002); Kimberly M. DaCosta, Making Multiracials: State, Family, and Marketing in Redrawing the Colon Line (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2007).

- This is a refinement of the two-category analytical schema of Stephen Cornell in “Variable Ties That Bind.” This analysis is carried through the history of one ethnic group in Paul R. Spickard, Japanese Americans: The Formation and Transformations of an Ethnic Group (New York: Twayne, 1996).

- Patrick Wolfe, Traces of History: Elementary Structures of Race (London: Verso, 2016): esp. 61-84, 141-202; Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, Not a Nation of Immigrants: Settler Colonialism, White Supremacy, and a History of Erasure and Exclusion (Boston: Beacon Press, 2021).

- Rudyard Kipling, “The White Man’s Burden,” McClure’s Magazine (February 1899). Kipling wrote on the occasion of United States annexation of the Philippines.

- Schäfer-Wünsche, “On Becoming German”; Djebali, “Ethnicity and Power in North Africa”; Richard S. Fogarty, “Between Subjects and Citizens: North Africans, Islam, and French National Identity during the Great War”; and Miyuki Yonezawa, “Memories of Japanese Identity and Racial Hierarchy,” all in Race and Nation, ed. Spickard; Fong and Spickard, “Ethnic Relations in the People’s Republic of China.” See also David Olusoga and Casper W. Erichsen, The Kaiser’s Holocaust: Germany’s Forgotten Genocide and the Colonial Roots of Nazism (New York: Faber and Faber, 2011); Martin Thomas, The French Colonial Mind, 2 vols. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2012); Sean R. Roberts, The War on the Uyghurs: China’s Internal Campaign against a Muslim Minority (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2020); Kirsten L. Ziomek, Lost Histories: Recovering the Lives of Japan’s Colonial Peoples (Cambridge, MA: Harvard East Asia Monographs, 2019); Patrick Wolfe, Traces of History: Elementary Structures of Race (London: Verso, 2016).

- Horsman, Race and Manifest Destiny; Matthew Frye Jacobson, Barbarian Virtues: The United States Encounters Foreign Peoples at Home and Abroad, 1876-1917 (New York: Hill and Wang, 2000); Thomas F. Gossett, Race: The History of an Idea in America (Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press, 1963).

- Antonio Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks of Antonio Gramsci (New York: International Publishers, 1971); Robert Blauner, Racial Oppression in America (New York: Harper and Row, 1972).

- Albert Memmi, The Colonizer and the Colonized (Boston: Beacon, 1965); see also Nadine Gordimer, “In the Penal Colonies: What Albert Memmi Saw and Did Not See,” Times Literary Supplement (September 12, 2003): 13-14.

- Barone, New Americans; Noel Ignatiev, How the Irish Became White (New York: Routledge, 1995); Karen Brodkin, How Jews Became White Folks and What That Says about Race in America (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1998); David R. Roediger, Working Toward Whiteness: How America’s Immigrants Became White: The Strange Journey from Ellis Island to the Suburbs, 2nd ed. (New York: Basic Books, 2018). For correctives, see Spickard, “What’s Critical About White Studies,” and Nell Irvin Painter, The History of White People (New York: Norton, 2010).

- Perry Miller, Errand into the Wilderness (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1956); Alden T. Vaughan, New England Frontier: Puritans and Indians, 1620-1675, rev. ed. (New York: Norton, 1979); Richard Drinnon, Facing West: The Metaphysics of Indian-Hating and Empire-Building (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1997; orig. 1980): 1-61.

- Robert Fisk, “Telling It Like It Isn’t,” Los Angeles Times (December 27, 2005).

- Isabel Johnston, “Words Matter: No Human Being Is Illegal,” Immigration and Human Rights Review (May 20, 2019); Adrian Florido, “The Evolution of the Immigration Term: Alien,” NPR: Morning Edition (August 19, 2015); Edwin F. Ackerman, “The Rise of the ‘Illegal Alien’,” Contexts, 12.3 (2013): 72-74.

- Elena Fiddian-Zasmiyeh, et al., eds., The Oxford Handbook of Refugee and Forced Migration Studies (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2014).

- E.g., Cheryl Shanks, Immigration and the Politics of American Sovereignty, 1890-1990 (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2001); Roger Daniels and Otis L. Graham, Debating American Immigration, 1882-Present (Lanham, Md.: Rowman and Littlefield, 2001); Juan F. Perea, Immigrants Out! The New Nativism and the Anti-Immigrant Impulse in the United States (New York: NYU Press, 1997).

- The Los Angeles Times is a prominent exception.

- Tuan, Forever Foreigners or Honorary Whites?, 1-3; “Senator D’Amato Apologizes for Faking Japanese Accent,” San Francisco Chronicle (April 6, 1995); Melinda Henneberger, “D’Amato Gives a New Apology on Ito Remarks,” New York Times (April 8, 1995).

Chapter 2

Discussion Questions

- How did early English colonists come to see themselves as American? Describe the process. What actions did they take to develop their identity as a people? Whom did they exclude?

- Explain how, during the eighteenth century, ideas about race and religion helped to define who was and who was not an American.

- Typically, in the history of American immigration, both indigenous populations of North America and Africans, whether free or enslaved, are not considered part of the immigration story. In this respect, how do the authors change the national narrative of immigration? According to the authors, who among the early Americans could be considered as non-immigrants?

Notes

- Walter Hölbling, “Thanksgiving,” a poem circulated to friends, November 2003. Used by permission of the poet.

- Italian Americans, by and large, were not sympathetic. California, Office of the Governor, “Governor Newsom Issues Proclamation Declaring Indigenous Peoples’ Day” (October 14, 2019).

- PBS News Hour, “Why more people are celebrating Indigenous Peoples’ Day” (October 14, 2019).

- Roxane Dunbar-Ortiz, An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States (Boston: Beacon Press, 2014).

- Lyle Campbell, American Indian Languages (New York: Oxford, 1997); Lyle Campbell and Marianne Mithun, eds., The Languages of Native America: Historical and Comparative Assessment (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1979); Marianne Mithun, The Languages of Native North America (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999). Here and elsewhere in this book, I have also used the expert essays in Frederick E. Hoxie, ed., Encyclopedia of North American Indians (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1996), and Carl Waldman, Atlas of the North American Indian, rev. ed. (New York: Checkmark, 2000).

- All three photographs come from Azusa Publishing, Inc. Kicks Iron was photographed by F. B. Fiske in about 1905. The photo of Tswawadi was taken by Charles H. Carpenter in 1904, and comes from the collection of the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago (Neg. #13583). Mishongnovi was photographed by A. C. Vroman in 1901 and comes to us courtesy of the Seaver Center, Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History. All are used by permission.

- London’s population ranged from 40,000 to 50,000 between 1300 and 1500, Rome’s from 20,000 to 40,000. Tertius Chandler and Gerald Fox, 3000 Years of Urban History (New York: Academic Press, 1974) 14-15, 34-35.

- Neal Salisbury, “The Indians’ Old World: Native Americans and the Coming of Europeans,” William and Mary Quarterly, 3d ser. 53 (1996), 435-58; Lynda Norene Shaffer, Native Americans Before 1492: The Moundbuilding Centers of the Eastern Woodlands (Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharp, 1992); Alice Beck Kehoe, America Before the European Invasion (London: Longman, 2002), 163-91; Peter Nabokov with Dean Snow, “Farmers of the Woodlands,” in Alvin M. Josephy, Jr., ed., America in 1492 (New York: Vintage, 1993), 118-45; Thomas E. Emerson, Cahokia and the Archaeology of Power (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1997); Colin G. Calloway, One Vast Winter Count: The Native American West Before Lewis and Clark (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2003); Stephen Warren, The Worlds the Shawnees Made: Migration and Violence in Early America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014); Michael McDonnell, Masters of Empire: Great Lakes Indians and the Making of America (New York: Hill and Wang, 2015).

- The Hohokam in southern Arizona and the Anasazi in the Four Corners region were large, complex, agriculture-based societies like the Mississippians. They lasted several centuries but declined before the coming of the Europeans. Bruce G. Trigger and William R. Swagerty, “Entertaining Strangers: North America in the Sixteenth Century,” in The Cambridge History of the Native Peoples of the Americas. Volume I: North America. Part 1, ed. Bruce G. Trigger and Wilcomb E. Washburn (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 325-98; Kehoe, America Before the European Invasions, 89-96, 138-62; Richard D. Daugherty, “People of the Salmon,” in Josephy, America in 1492, 48-83; Ned Blackhawk, Violence Over the Land: Indians and Empires in the Early American West (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008); Pekka Hämäläinen, Lakota America: A New History of Indigenous Power (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2019).

- Robert Berkhofer, Jr., The White Man’s Indian: Images of the Indian from Columbus to the Present (New York: Knopf, 1978), 4.

- Russell Thornton makes the following population estimates for various parts of the world about 1500 in American Indian Holocaust and Survival: A Population History Since 1492 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1987), 37.

- These are conservative figures. Other estimates for America north of Mexico range as high as ten million. William M. Denevan, The Native Population of the Americas in 1492, 2nd ed. (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1992), xxviii; Thornton, American Indian Holocaust and Survival; Russell Thornton, “North American Indians and the Demography of Contact,” in Race, Discourse, and the Origin of the Americas, ed. Vera Lawrence Hyatt and Rex Nettleford (Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 1995), 213-30; Thornton, “The Demography of Colonialism and ‘Old’ and ‘New’ Native Americans,” in Studying Native America, ed. Thornton (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1998), 17-39; David E. Stannard, Before the Horror: The Population of Hawai‘i on the Eve of Western Contact (Honolulu: Social Science Research Institute, University of Hawai‘i, 1989); Campbell Gibson and Kay Jung, “Historical Census Statistics on Population totals by Race, 1790 to 1990, and by Hispanic Origin, 1970 to 1990, for the United States, Regions, Divisions, and States,” Population Division, Working Paper No. 56 (Washington, DC: US Census Bureau, 2002), Table 1.

- Kehoe, America Before the European Invasions: 8-21; Dean R. Snow, “The First Americans and the Differentiation of Hunter-Gatherer Cultures,” in Cambridge History of the Native Peoples of the Americas. Volume I. Part 1, ed. Trigger and Washburn, 61-124; E. James Dixon, Quest for the Origins of the First Americans (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1993); Tom D. Dillehay, The Settlement of the Americas: A New Prehistory (New York: Basic Books, 2000); David E. Stannard, American Holocaust: The Conquest of the New World (New York: Oxford, 1992), 261-68; David Treuer, The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee: Native America from 1890 to the Present (New York: Riverhead, 2019): 19-44.

- Joel W. Martin, The Land Looks After Us: A History of Native American Religion (New York: Oxford, 2001); Albert Yava, Big Falling Snow: A Tewa-Hopi Indian’s Life and Times and the History and Traditions of His People, ed. Harold Courlander (New York: Crown, 1978); Paul Spickard, James V. Spickard, and Kevin M. Cragg, World History by the World’s Historians (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1998), 6-15.

- Dennis J. Stanford and Bruce A. Bradley, Across Atlantic Ice: The Origin of America’s Clovis Culture (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012); Ivan Van Sertima, They Came Before Columbus: The African Presence in Ancient America (New York: Random House, 1976); David H. Kelley, “An Essay on Pre-Columbian Contacts between the Americas and other Areas, with Special Reference to the Work of Ivan Van Sertima,” in Race, Discourse, and the Origin of the Americas, ed. Hyatt and Nettleford: 103-22; Ben R. Finney, Sailing in the Wake of the Ancestors: Reviving Polynesian Voyaging (Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press, 2003); David Lewis, We, the Navigators: The Ancient Art of Landfinding in the Pacific, 2nd ed. (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 1994); Annette Kolodny, In Search of First Contact: The Vikings of Vinland, the Peoples of the Dawnland, and the Anglo-American Anxiety of Discovery (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012); Louise Levathes, When China Ruled the Seas: The Treasure Fleet of the Dragon Throne, 1405-1433 (New York: Oxford, 1996); Gavin Menzies, 1421: The Year China Discovered America (New York: Morrow, 2003); Rafique Ali Jairazbhoy, Ancient Egyptians and Chinese in America (Totowa, N.J.: Rowman and Littlefield, 1974); C. G. Leland, Fusang: The Discovery of America by Chinese Buddhist Priests in the Fifth Century (New York: Barnes and Noble, 1973; orig. 1875); Helge M. Ingstad, Westward to Vinland (New York: St. Martin’s, 1969).

- In like manner, Hawaiians will be treated as the original inhabitants of what is now the fiftieth state. Although their ancestors came to the islands in remembered time, they came several centuries before European and Asian incursions.

- Matthew Restall, ”Black Conquistadors: Armed Africans in Early Spanish America.” The Americas, Vol. 57, No. 2, The African Experience in Early Spanish America (Oct. 2000), pp. 171-205; Matthew Restall, Maya Conquistador (Boston: Beacon press, 1999); Matthew Restall, Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004); Laura E. Matthew, ed., and Michel R. Oudijk, Indian Conquistadors: Indigenous Allies in the Conquest of Mesoamerica (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2012); Laura E. Matthew, Memories of Conquest: Becoming Mexicano in Colonial Guatemala (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014).

- Waldman, Atlas of the North American Indian, 190.

- Sherburne F. Cook and Woodrow Borah, “The Aboriginal Population of Hispaniola,” in Cook and Borah, Essays in Population History. Volume 1. Mexico and the Caribbean, 1600-1860 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973), 376-410; Stannard, American Holocaust, 58-146; Ida Altman, Sarah Cline, and Juan Javier Pescador, The Early History of Greater Mexico (Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Prentice Hall, 2003), 53-113; Catherine M. Cameron, et al., eds., Beyond Germs: Native Depopulation in North America (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2015).

- Altman, Cline, and Pescador, Early History of Greater Mexico, 185-201; David J. Weber, The Spanish Frontier in North America (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1992), 60-91; Weber, ed., What Caused the Pueblo Revolt of 1680? (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 1999); Weber, ed., New Spain’s Far Northern Frontier (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1979); Blackhawk, Violence Over the Land; Robbie Ethridge, From Chicaza to Chickasaw: The European Invasion and the Transformation of the Mississippian World, 1540-1715 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010).

- W. J. Eccles, The French in North America, 1500-1783, rev. ed. (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 1998); Eccles, France in America (New York: Harper and Row, 1972); Russell Shorto, Island at the Center of the World: The Epic Story of Dutch Manhattan, the Forgotten Colony that Shaped America (New York: Doubleday, 2004). Here and elsewhere in this chapter I have had occasion to rely also on Gary B. Nash, Red, White, and Black: The Peoples of Early America (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1974).

- Chrestien LeClerq, New Relation of Gaspesia, with the Customs and Religion of the Gaspesian Indians, trans. and ed. William F. Ganong (Toronto: Champlain Society, 1910), 104-06, quoted in Colin G. Galloway, ed., The World Turned Upside Down: Indian Voices from Early America (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 1994), 50-52.

- Berkhofer, White Man’s Indian, 28.

- Stannard, American Holocaust, 247; see also Francis Jennings, The Invasion of America: Indians, Colonialism, and the Cant of Conquest (New York: Norton, 1976).

- Nash, Red, White, and Black, 34-43.

- Cornelius J. Jaenen, “Amerindian Views of French Culture in the Seventeenth Century,” Canadian Historical Review, 55 (1974), 261-91.

- Nancy Shoemaker, A Strange Likeness: Becoming Red and White in Eighteenth-Century North America (New York: Oxford, 2004); Kathleen DuVal, The Native Ground: Indians and Colonists in the Heart of the Continent (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007); Jace Weaver, The Red Atlantic: American Indigenes and the Making of the Modern World, 1000-1927 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014): 1-85.

- Charlotte J. Erickson, “English,” in Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1980), 319-36. I have used various of the essays in this encyclopedia in this chapter and throughout the book. For population figures for the entire incipient United States, see Appendix, Table 1.

- David Beers Quinn, Set Fair for Roanoke: Voyages and Colonies, 1584-1606 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1985).

- Ibid.

- Except where otherwise noted, information on the Jamestown encounter with Powhatan’s people is taken from: Edmund S. Morgan, American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia (New York: Norton, 1975), 44-91; David Price, Love and Hate in Jamestown: John Smith, Pocahontas, and the Heart of a New Nation (New York: Knopf, 2003); Helen C. Rountree, ed., Powhatan Foreign Relations (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1993); Frederic W. Gleach, Powhatan’s World and Colonial Virginia (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1997); Wesley Frank Craven, White, Red, and Black: The Seventeenth-Century Virginian (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1971), 39-71; Philip L. Barbour, Pocahontas and Her World (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1970); Frances Mossiker, Pocahontas: The Life and the Legend (New York: Knopf, 1976); Helen C. Rountree, “Pocahontas: The Hostage Who Became Famous,” in Sifters: Native American Women’s Lives, ed. Theda Perdue (New York: Oxford, 2001), 14-28.

- Philip L. Barbour, ed., The Complete Works of Captain John Smith (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1986), 1:247.

- Vaughan, Puritan Frontier, 64-92; Nash, Red, White, and Black, 76-80; Francis J. Bremer, The Puritan Experiment: New England Society from Bradford to Edwards (New York: St. Martin’s, 1976), 42-56.

- Vaughan, loc. cit.; Neal Salisbury, Manitou and Providence: Indians and Europeans in the Making of New England, 1500-1643 (New York: Oxford, 1982); Salisbury, “Squanto: Last of the Patuxets,” in Struggle and Survival in Colonial America, ed. David G. Sweet and Gary B. Nash (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1981), 228-46

- Thornton, American Indian Holocaust and Survival, 60-90; David E. Stannard, Before the Horror: The Population of Hawai‘i on the Eve of Western Contact (Honolulu: Social Science Research Institute, University of Hawai‘i, 1989); Stannard, American Holocaust, 95; Susan Sleeper Smith, “Encounter and Trade in the Early Atlantic World,” in Why You Can’t Teach United States History without American Indians, ed. Susan Sleeper-Smith, et al. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015): 26-42; Cameron, et al., Beyond Germs.

- John Winthrop, “Generall Considerations for the Plantation in New England . . .” (1629), in Winthrop Papers, 5 vols., ed. Allyn B. Forbes (Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society, 1929-47), 2:118; quoted in Nash, Red, White, and Black, 80.

- Gleach, Powhatan’s World.

- Vaughan, New England Frontier, 123-54; Richard Drinnon, Facing West: The Metaphysics of Indian-Hating and Empire-Building (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1997), 35-61.

- Russell Bourne, The Red King’s Rebellion: Racial Politics in New England, 1675-1678 (New York: Atheneum, 1990); Jill Lepore, The Name of War: King Philip’s War and the Origins of American Identity (New York: Knopf, 1998).

- Francis Jennings, The Invasion of America: Indians, Colonialism, and the Cant of Conquest (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1975), 146-70; Stannard, American Holocaust, 118-19. Among the many analyses of Serbian genocide in Bosnia is Genocide in Bosnia: The Policy of Ethnic Cleansing, by Norman Cigar and Stjepan G. Mestrovic (College Station: Texas A & M Press, 1995); DuVal, Native Ground; Ethridge, Chikaza.

- Ramón Gutierrez, When Jesus Came, the Corn Mothers Went Away: Marriage, Sexuality, and Power in New Mexico, 1500-1846 (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1991), 130-40; Jack D. Forbes, Apache, Navaho, and Spaniard (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1994; orig. 1960), 200-49; David J. Weber, ed., What Caused the Pueblo Revolt of 1680? (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 1999); Weber, The Spanish Frontier in North America (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1992), 133-45; Pekka Hämäläinen, “The Rise and Fall of Plains Indian Horse Cultures,” Journal of American History (December 2003), 833-62; Pekka Hämäläinen, The Comanche Empire (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008).

- Matthew Dennis, Cultivating a Landscape of Peace: Iroquois-European Encounters in Seventeenth-Century America (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1993); Nash, Red, White, and Black, 17-25, 239-75; Theda Perdue, “Mixed Blood” Indians: Racial Construction in the Early South (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2003); Amy Turner Bushnell, “Ruling ‘The Republic of Indians’ in Seventeenth-Century Florida,” in Powhatan’s Mantle: Indians in the Colonial Southeast, ed. Peter H. Wood, Gregory A. Waselkov, and M. Thomas Hatley (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1989), 134-50.

- James Axtell, “The White Indians of Colonial America,” William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd series, 32 (1975), 55-88.

- Perdue, “Mixed Blood” Indians; Robbie Ethridge, Creek Country: The Creek Indians and Their World (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003); Rebecca Anne Goetz, The Baptism of Early Virginia: How Christianity Created Race (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012).

- That is, if one does not regard Africans as a single group. See the next section, “Out of Africa,” for that issue.

- David Hackett Fischer, Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America (New York: Oxford, 1989). For a broader view of European migration to the Americas, in terms of both the origins and the destinations of migrants, see Eric Hinderaker and Rebecca Horn, European Emigration to the Americas, 1492 to Independence: A Hemispheric View (New York: Oxford, 2020).

- Bernard Bailyn, The Peopling of British North America (New York: Knopf, 1986), 25, 40; Bernard Bailyn, The Barbarous Years: The Peopling of British North America: The Conflict of Civilizations, 1600-1675 (New York: Knopf, 2012); Carl Bridenbaugh, Vexed and Troubled Englishmen, 1590-1642 (New York: Oxford, 1968), 203-08. Contra Bailyn, it is worth remembering that North America was already peopled before the first British migrant left shore.

- Walter Woodward, “Jamestown Estates,” William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd ser., 47 (1991), 116-17.

- Sources on the Puritans include Francis Bremer, The Puritan Experiment: New England Society from Bradford to Edwards (New York: St. Martin’s, 1976); Alan Simpson, Puritanism in Old and New England (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1955); Edmund S. Morgan, The Puritan Dilemma: The Story of John Winthrop (Boston: Little, Brown, 1958); Fischer, Albion’s Seed: 13-205; John Demos, A Little Commonwealth: Family Life in Plymouth Colony (New York: Oxford, 1970); William Bradford, Of Plymouth Plantation (New York: Knopf, 1952); Edmund S. Morgan, Visible Saints: The History of a Puritan Idea (New York: New York University Press, 1963); Carol F. Karlsen, The Devil in the Shape of a Woman: Witchcraft in Colonial New England (New York: Norton, 1987); John Demos, Entertaining Satan: Witchcraft and the Culture of Early New England (New York: Oxford, 1982).

- On the Halfway Covenant, see Edmund S. Morgan, Visible Saints: The History of a Puritan Idea (New York: New York University Press, 1963), 113-38.

- Fischer, Albion’s Seed: 207. The material for this section is taken from Morgan, American Slavery, American Freedom, and Fischer, Albion’s Seed, 207-418.

- On indentured servitude, see Abbot Emerson Smith, Colonists in Bondage: White Servitude and Convict Labor in America, 1607-1776 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1947); P. C. Emmer, ed., Colonialism and Migration: Indentured Labour Before and After Slavery (Dordrecht: Martinus Nijhoff, 1986); David W. Galenson, White Servitude in Colonial America (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981).

- On Bacon’s Rebellion, see varying interpretations in Wilcomb E. Washburn, The Governor and the Rebel: A History of Bacon’s Rebellion in Virginia (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1957); Thomas J. Wertenbaker, Bacon’s Rebellion, 1676 (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1957); Nash, Red, White, and Black, 127-34; Ronald Takaki, A Different Mirror: A History of Multicultural America (Boston: Little, Brown, 1993), 60-68; Morgan, American Slavery, American Freedom, 215-70; Theodore W. Allen, The Invention of the White Race: The Origin of Racial Oppression in Anglo-America (London: Verso, 1997).

- Fischer, Albion’s Seed, 419-603; Joseph E. Illick, Colonial Pennsylvania (New York: Scribner’s, 1976); Sally Schwartz, “A Mixed Multitude”: The Struggle for Toleration in Colonial Pennsylvania (New York: New York University Press, 1988).

- It also encouraged migration by Africans, but as slaves rather than servants or free laborers; see below.

- Morgan, American Slavery, American Freedom, 94, 171-73, 405-06.

- Michael LeMay and Elliott Robert Barkan, eds., U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Laws and Issues: A Documentary History (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood, 1999), 6-9.

- Jacob Van Hinte, Netherlanders in America, ed. Robert P. Swierenga, trans. Adriaan de Wit (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker Book House, 1985), 3-51; Shorto, Island at the Center of the World.

- Aaron Spencer Fogleman, Hopeful Journeys: German Immigration, Settlement, and Political Culture in Colonial America, 1717-1775 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1996); A. G. Roeber, “ ‘The Origin of Whatever Is Not English among Us’: The Dutch-speaking and the German-speaking Peoples of Colonial British America,” in Strangers within the Realm: Cultural Margins of the First British Empire, ed. Bernard Bailyn and Philip D. Morgan (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991), 220-83; Don Heinrich Tolzmann, The German-American Experience (Amherst, N.Y.: Prometheus, 2000), 21-94.

- Sources on German immigration in this period include Steven M. Nolt, Foreigners in Their Own Land: Pennsylvania Germans in the Early Republic (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2002); A. G. Roeber, Palatines, Liberty, and Property: German Lutherans in Colonial British America, rev. ed. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998); Aaron Spencer Fogleman, Hopeful Journeys: German Immigration, Settlement, and Political Culture in Colonial America, 1717-1775 (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1996); Sally Schwartz, “A Mixed Multitude”: The Struggle for Toleration in Colonial Pennsylvania (New York: New York University Press, 1987), 81-119; Joseph E. Illick, Colonial Pennsylvania (New York: Scribner’s 1976), 113-36; Philip Otterness, Becoming German: The 1709 Palatine Migration to New York (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2004). One highly visible German immigrant was Baron Friedrich von Steuben, an openly gay Prussian military officer who trained American troops in the war for independence from Britain. See Paul Lockhart, Drillmaster of Valley Forge: The Baron de Steuben and the Making of the American Army (New York: HarperCollins, 2008); William Benemann, Male-Male Intimacy in Early America: Beyond Romantic Friendships ({Philadelphia: Haworth Press, 2006).

- Fogleman, Hopeful Journeys, esp. 80-86, 131-35, 149-53.

- Maldwyn Jones, “Scotch-Irish,” in Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups, 895-908. Other sources for this section include Fischer, Albion’s Seed, 605-782; James G. Leyburn, The Scotch-Irish (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1963); Carl Bridenbaugh, Myths and Realities: Societies of the Colonial South (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1952), 119-96; Patrick Griffin, The People with No Name: Ireland’s Ulster Scots, America’s Scots Irish, and the Creation of a British Atlantic World, 1689-1764 (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2001); Maldwyn A. Jones, “The Scotch-Irish in British America,” in Strangers within the Realm, 284-313; J. P. MacLean, An Historical Account of the Settlements of Scotch Highlanders in America Prior to the Peace of 1783 (Cleveland, 1900); David Dobson, The Scottish Emigration to Colonial America, 1607-1785 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1994); Tyler Blethen and Curtis W. Wood, Ulster and North America: Transatlantic Perspectives on the Scotch-Irish (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1997).

- Samuel Johnson, A Journey to the Western Isles of Scotland, ed. Mary Lascelles (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1971; orig. 1775), 95.

- James Boswell, Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides, ed. Frederick A. Pottle and Charles H. Bennett (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1936; orig. 1773), 242-43; italics added.

- Gottlieb Mittelberger, Journey to Pennsylvania, ed. and trans. Oscar Handlin and John Clive (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1960), 12-13.

- Ibid., 17-19.

- Richard Hofstadter, America at 1750: A Social Portrait (New York: Knopf, 1971), 22-65.

- Mittelberger, Journey to Pennsylvania, 21.

- Kariann Akemi Yokota, Unbecoming British: How Revolutionary America Became a Post-Colonial Nation (New York: Oxford, 2011); Benjamin Franklin, The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin, ed. Louis P. Masur (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 1993); Walter Isaacson, Benjamin Franklin (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2003); Max Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, trans. Talcott Parsons (New York: Scribner, 1958), 79-92; Richard L. Bushman, From Puritan to Yankee: Character and the Social Order in Connecticut, 1690-1765 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1967), ix; Philip J. Greven, Jr., Four Generations: Population, Land, and Family in Colonial Andover, Massachusetts (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1970).

- David Brion Davis, In the Image of God: Religion, Moral Values, and Our Heritage of Slavery (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2001), quoted in William H. McNeill, “The Big R,” New York Review of Books (May 23, 2002), 58.

- I use the term “Negro” here advisedly, for it was the common term that both non-African-descended people and African-descended people used in the period under examination.

- Venture Smith, A Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Venture, A Native of Africa . . . (New London, Conn., 1798), quoted in Thomas R. Frazier, ed., Afro-American History: Primary Sources, 2nd ed. (Chicago: Dorsey, 1988), 8-9

- Olaudah Equiano, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, ed. Robert J. Allison (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 1995; orig. 1789), 52-54.

- Ibid., 57-58.

- Ibid., 59.

- A good place to start on the other vast slave movement out of Africa is Ronald Segal, Islam’s Black Slaves: The Other Black Diaspora (New York: Hill and Wang, 2001). See also Patrick Manning, Slavery and African Life: Occidental, Oriental, and African Slave Trades (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1990); Michael A. Gomez, Reversing Sail: A History of the African Diaspora (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2005); Emma Christopher, et al., Many Middle Passages: Forced Migration and the Making of the Modern World (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007).

- The numbers here are based on my estimates of the numbers displayed in three-dimensional bar graph form. Gemery and Menard’s estimates for Africans are lower than several other demographers’. Accordingly, I have supplemented them with information from Philip D. Curtin, The Atlantic Slave Trade: A Census (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1969), 140. See also Henry A. Gemery, “Emigration from the British Isles to the New World, 1630-1700: Inferences from Colonial Populations,” Research in Economic History, 5 (1980), 179-231; Gemery, “European Emigration to North America, 1700-1820: Numbers and Quasi-Numbers,” Perspectives in American History, New Series, 1 (1984), 283-343; Gemery, “The White Population of the Colonial United States, 1607-1790,” in A Population History of North America, ed. Michael R. Haines and Richard H. Steckel (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 143-90; Philip D. Curtin, The Atlantic Slave Trade: A Census (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1969), 140; Paul E. Lovejoy, “The Volume of the Atlantic Slave Trade: A Synthesis,” Journal of African History, 23 (1982), 473-501); Joseph Inikori and Stanley L. Engerman, eds., The Atlantic Slave Trade (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1992); James A. Rawley, The Transatlantic Slave Trade (New York: Norton, 1981), 167; Michael A. Gomez, Exchanging Our Country Marks: The Transformation of African Identities in the Colonial and Antebellum South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998), 20.

- David Northrup, ed., The Atlantic Slave Trade, 3rd ed. (Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, 2011); Walter Rodney, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa (Washington: Howard University Press, 1974), 95-118; Rodney, A History of the Upper Guinea Coast, 1545-1800 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1970). For contrasting views, see Patrick Manning, “Contours of Slavery and Social Change in Africa,” American Historical Review, 88.4 (1983), 836-57; David Eltis, “Precolonial Western Africa and the Atlantic Economy,” in Slavery and the Rise of the Atlantic System, ed. Barbara Solow (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 97-119; Henry A. Gemery and Jan S. Hogendorn, eds., The Uncommon Market: Essays in the Economic History of the Atlantic Slave Trade (New York: Academic Press, 1979).

- L. S. Stavrianos, Global Rift: The Third World Comes of Age (New York: Morrow), 99-121, 196-204; Herman L. Bennett, African Kings and Black Slaves: Sovereignty and Dispossession in the Early Modern Atlantic (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019).

- This interpretation comes from several sources: Winthrop D. Jordan, The White Man’s Burden: Historical Origins of Racism in the United States (New York: Oxford, 1974), 3-54; Jordan, White Over Black: American Attitudes Toward the Negro, 1550-1812 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1968), 3-98; David Brion Davis, Slavery and Human Progress (New York: Oxford, 1984); Betty Wood, The Origins of American Slavery (New York: Hill and Wang, 1997); Alden T. Vaughan, “The Origins Debate: Slavery and Racism in Seventeenth-Century Virginia,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 97.3 (1989), 311-54.

- Allan Gallay, The Indian Slave Trade (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2002); Andrés Reséndez, The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016).

- Kenneth Morgan, Slavery and Servitude in Colonial North America (New York: New York University Press, 2001); Ira Berlin, Many Thousands gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1998); Winthrop D. Jordan, “American Chiaroscuro: The Status and Definition of Mulattoes in the British Colonies,” William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd ser., 19 (1962), 183-200.

- Robert Beverley, The History and Present State of Virginia, ed. Louis B. Wright (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1947; orig. 1705), 235-36.

- These numbers come from a variety of sources. See those listed under Table 2.5, as well as Berlin, Many Thousands Gone: appendices.

- Sources for the variety of slave patterns in the southern colonies include Berlin, Many Thousands Gone; Nash, Red, White, and Black; Morgan, American Slavery, American Freedom; Philip D. Morgan, Slave Counterpoint: Black Culture in the Eighteenth-Century Chesapeake and Lowcountry (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998); Peter H. Wood, Black Majority: Negroes in Colonial South Carolina from 1670 through the Stono Rebellion (New York: Knopf, 1974); Daniel C. Littlefield, Rice and Slaves: Ethnicity and the Slave Trade in Colonial South Carolina (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1981); Betty Wood, Slavery in Colonial Georgia, 1730-1775 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1984).