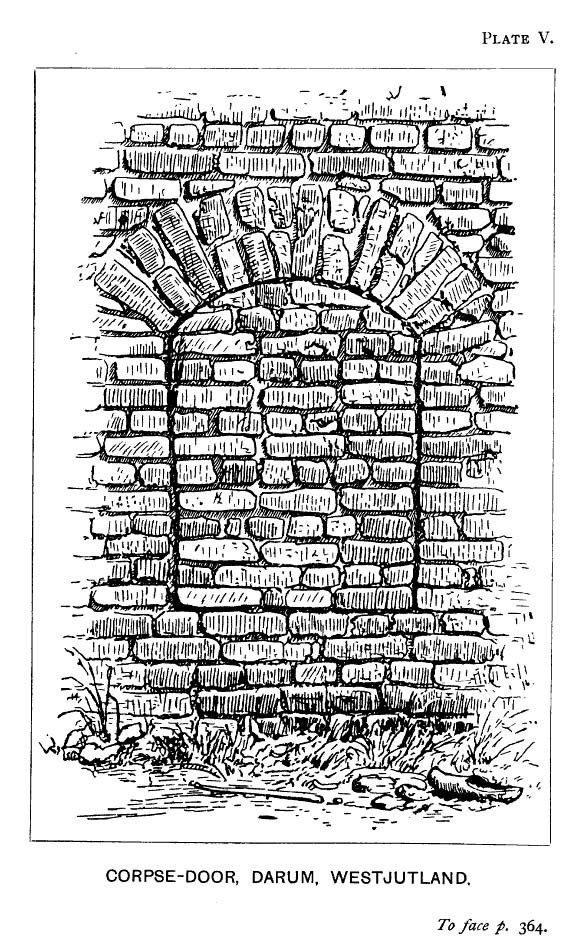

Welcome to the companion website for Mummies, Cannibals and Vampires: The History of Corpse Medicine from the Renaissance to the Victorians, 2nd edition, by Richard Sugg.

This unique book charts the largely forgotten history of European corpse medicine in vivid detail to show that, far from being a medieval therapy, corpse medicine was at its height during the social and scientific revolutions of early-modern Britain and lingered stubbornly on into the time of Queen Victoria.

On this dedicated companion website you will find additional articles, interviews and resources to help you explore this fascinating topic further. Resources on this website include:

- Summaries of key topics

- A glossary

- Links to related media articles

- Interviews and articles from the author