Introduction

Roman literature

‘I salute thee, Mantovano,

I that loved thee since my day began,

Wielder of the stateliest measure

Ever moulded by the lips of man.’(Alfred, Lord Tennyson, ‘To Virgil’, ll. 37–40)

Three of the many dialects that wandering immigrants first brought to the Italian peninsula emerged as contenders for the ultimate language of the region: Umbrian, Oscan and Latin. The last of these, which was used in the comparatively small area of Latium, had been enriched by an admixture of features of local Sabine and Etruscan speech, and much more significantly by Greek.

The historical Trojan War took place in about 1220 BC, and legend has it that soon afterwards Greek settlers came to Italy. Certainly there was a Greek trading post in the Bay of Naples by 775 BC, and the fifty years or so after the traditional date for the founding of Rome (753 BC) coincide with the composition of the Greek epic poems, the Odyssey and the Iliad, and the establishment and circulation through the Greek world of the Greek alphabet.

The domination of one dialect over another is usually due to external rather than linguistic features. In the case of Latin, it was Roman military expansion which caused it to become the first language of the Italian peninsula as well as the second, if not the first, wherever Rome’s conquests lay.

From the Latin alphabet is derived the English alphabet, and to all intents and purposes they are the same. Since it is not known exactly how Latin was pronounced, anyone without any knowledge of Latin who reads it aloud cannot go very far wrong. This is important because, whereas the flowering of English literature, for instance, occurred after the introduction of printing, much of Latin literature was expressly written to be read aloud or recited.

To the Romans, the Latin word liber meant anything that was written, but particularly a book. The equivalent of our ‘book’ was volumen, meaning roll. This was a roll of papyrus up to ten metres long and thirty centimetres wide, with a rod fixed at each end, on which the work was written in columns about ten centimetres wide. As you read, you rolled up the used portion with the left hand while unrolling the next section with your right.

The most striking feature of Latin is its use of inflections: changes in the form of a word to indicate, for example, gender, number, case, person, degree, voice, mood or tense. The order of words within a sentence was flexible and could be varied for the sake of emphasis, different minutiae of meaning, or simply rhythm. Alliteration was widely used in both verse and prose, but rhyme only rarely, and then usually internally in prose.

Poetry was written in prescribed metre patterns, made up of short and long syllables, arranged in feet, as in Shakespeare’s line:

This is the classic iambic pentameter of five feet, each comprising one short and one long syllable; it is the basis of all the verse in Shakespeare’s plays.

The equivalent line in Latin poetry is the dactylic hexameter (borrowed from the Greek) of six feet, each comprising one long and two short syllables, or two long syllables, with a break in the middle of the third foot called a caesura. We can apply this to the first line of Virgil’s Aeneid:

‘I sing of arms and the man who first from Trojan shores . . .’

In Latin, when the letter ‘i’ comes before a vowel in the same syllable, as in ‘Troiae’, it has the effect of the English y, as in ‘you’. In modern English it is represented by, and sounded as, the letter ‘j’, as in ‘junior’ (Latin iunior) and ‘Julius’ (Latin Iulius).

In English prosody iambic pentameters rhyming in pairs are known as heroic couplets, a form perfected by John Dryden (1631–1700) and Alexander Pope (1688–1744), and into which Dryden translated works of Virgil and Juvenal. The equivalent in Latin is the graceful elegiac couplet: a dactylic hexameter followed by a pentameter, a line of five feet comprising two parts, each of two-and-a-half feet.

‘Cynthia’s dear eyes were the first to ensnare my luckless self, never till then aroused by love’s desires.’

(Propertius, Elegies 1.1.1–2)

Another Greek metre, the hendecasyllable, widely used, especially by Catullus and Martial, comprises eleven syllables:

‘Come, Lesbia, let’s live and love.’

(Catullus, Poems 5.1)

Note that where a word which ends in a vowel precedes one which begins with a vowel, the former vowel is ‘elided’ or suppressed.Ennius

Quintus Ennius (239–169 BC), regarded as the father of Latin poetry, was born of Greek parentage in Rudiae, Calabria, the ‘heel’ of Italy. As well as Greek, he spoke Latin and the local Oscan dialect. As a Roman subject he served in Sardinia in the Second Punic War. He was still in Sardinia, presumably as a member of a garrison, in 204 BC, for there he met Cato, then praetor, who took him back to Rome. Ennius lived frugally, writing and earning a living by teaching the sons of the nobility. He was granted Roman citizenship in 184 BC.

Ennius wrote over twenty stage tragedies, mainly on Greek themes, as well as some comedies and occasional verses. His main work, on which he was engaged for the last twenty years of his life, was a massive verse history of Rome in eighteen books. For this he abandoned the rough and barely perceptible rhythms of earlier Latin poets for the stately and musical measures of the hexameter, which he forged into the epic medium later used by Virgil. We have only fragments of his work, totalling some 600 lines, which may not be his best, but he was often quoted by later writers.

Examples of Ennius’ hexameters:

- sparsis hastis longis campus splendet et horret

- introducuntur legati Minturnenses

and the famous one about Q. Fabius Maximus, quoted by Virgil:

- unus homo nobis cunctando restituit rem

Comedy: Plautus and Terence

The first comic dramas that the Romans saw were based on the Greek ‘new comedies’ of the kind staged in Athens from about 400 to 200 BC. Their hallmarks included stratagems and counter-stratagems, stock characters (young lovers, scheming slave, family hanger-on), and standard situations (obstacles to young love, mistaken identities, revelations of true identity), with some musical accompaniment.

The principal writer of the Greek ‘new comedy’ was Menander (342–c. 292 BC), who influenced Plautus and Terence.

Titus Maccus Plautus (254–184 BC) was not the first of these Roman dramatists, but of 130 plays attributed to him, 20 have survived. This in itself would be a measure of his popularity, but in addition, although it is based on earlier Greek models, his work retains a raw freshness of its own. He devised ways of adapting Greek verse metres to the Latin language, and introduced to audiences whose taste had tended towards farce and slapstick several varieties of literary comedy, such as burlesque and domestic and romantic pieces in which verbal fireworks replaced crude banter. He also surmounted the problem of playing consecutive scenes, without any break between them, in front of a standard backdrop, usually a street with entrances to two houses.

Plautus was born in Sarsina, a small village in Umbria, but left home early to go to Rome. He first worked as a stage props-man, and then, with the money he had earned, set himself up in some kind of business. When that failed, he took a job turning a baker’s handmill, which he was able to give up after writing his first three plays.

Publius Terentius Afer (c. 185–159 BC) was brought to Rome as a slave, possibly from Africa. He took his name from that of his owner, Terentius Lucanus, who educated him and gave him his freedom. The story goes that he submitted his first play, The Girl from Andros, to the curule aediles; in turn, they referred him to Caecilius Statius (c. 219–c. 166 BC), the most popular playwright of the day. Caecilius was dining when Terence called, but he immediately began reading the play aloud. He was so impressed that he invited Terence to share the couch of honour with him. The play was first performed in 166 BC, and Terence wrote five more before he died in a shipwreck, or of disease, while on a trip to Greece to find more plots. He was only about twenty-six.

Terence’s plays are better plotted than those of Plautus and indeed of some of the originals that he adapted. The comedy of manners effectively began with him. He was adept at employing the double plot, especially to illustrate different characters’ responses to a situation, and in developing the situation itself. There is also more purity of language and characterization than in Plautus, which may explain why Terence was not as popular in his own day as he would become later.

Lucretius

In the dark, confused days presaging the end of the republic, voices were abroad which questioned prevailing views about the natural and spiritual worlds. Some of these belonged to the Epicureans, a school of Greek philosophy founded by Epicurus (341–270 BC) whose tenets included a rudimentary theory of the atomic nature of matter. Epicurus believed, too, that every happening had a natural cause and that the ultimate aim in life was the pleasure that could be derived from the harmony of body and mind.

Among the staunchest followers of Epicureanism in Italy was Titus Lucretius Carus (c. 99–55 BC). His De Rerum Natura (On the Nature of Things) comprises the first six books, some 7,500 hexameters, of an unfinished philosophical poem that is unique in Latin. It is a work of great learning and great poetry; also of considerable insight, in that while subscribing to the Epicurean objection to spiritual gods and their images, he anticipated the kind of dilemma the modern biologist has with regard, for instance, to Christianity.

So Lucretius invests Venus, whom he invokes at the beginning of the poem, with an overall creative power in nature, before entering into his exposition of the composition of matter and space in atomic terms. He goes on to discuss the mind, life itself, feeling, sex, thought, cosmology, anthropology, meteorology and geology. De Rerum Natura is thus not so much a philosophical work as a scientific treatise; it is a mark of the skill of Lucretius that he succeeded in presenting it in the language and metre of poetry.

Lyric poetry: Catullus and Horace

Lyric poetry has come to mean that in which the composer presents his or her personal thoughts and feelings. Originally, it simply meant poetry or a song accompanied by the lyre, for which the Greeks used a variety of metres.

The Romans took over the metres, though not necessarily the accompaniment, and employed them in a rather more precise form to express themselves poetically.

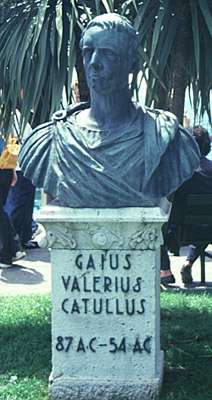

Gaius Valerius Catullus (87–54 BC) was born in Verona, probably into a moderately rich family. After arriving in Rome in about 62 BC, he became one of the wave of ‘new poets’ who reacted against their elders while, from the evidence of his own poetry, boozing, whoring and generally living it up.

Catullus moved in high circles, too, especially if the woman he calls Lesbia in his poems, and with whom he had a blazing affair, was Clodia, the emancipated and profligate sister of Cicero’s enemy Publius Clodius and the wife of Metellus Celer, consul in 60 BC. In 57 BC, Catullus was the guest, or camp-follower, of Memmius, governor of Bithynia, and the man to whom Lucretius dedicated De Rerum Natura. He died soon after returning to Italy.

We have just 116 of Catullus’ poems, varying in length from 2 to 480 lines, as well as a few fragments; this probably represents the whole of his published work. As well as the famous love/hate poems to Lesbia/Clodia – which are by turns passionate, tender and sometimes indignant – there are bitingly observant cameos of friends and enemies, and of chance meetings and alfresco sexual encounters, in which Catullus is often coarse but always amusing. Others, including his longest (Poem 64), an account in hexameters of the wedding of Peleus and Thetis, have mythological themes, but still show considerable depth of poetic emotion.

Whereas Catullus often wrote in the passions of the moment, Quintus Horatius Flaccus (65–8 BC) had the leisure and the time to marshal his thoughts into lines which usually display more grace and artifice, but less emotion.

Horace was born in Venusia, Apulia, the son of a freedman who made a good living for himself and acquired a small estate. He was taken by his father to Rome, where he was sent to the best schools. At eighteen, he was caught up in the Greek civil wars following the assassination of Caesar, and fought at Philippi on the wrong side. He was pardoned, but when he returned to Rome he found that his father’s estate had been confiscated. He became a civil service clerk, and in his spare time wrote verses that caught the eye of Virgil, who introduced him to his own patron, Gaius Maecenas (c. 70–8 BC). A few years later Maecenas set him up in a farm near Tibur (Tivoli), the remains of which survive. Between this farm, a cottage in Tibur and a house in Rome, Horace lived out his existence as a bachelor with, when it suited him, Epicurean tendencies.

Horace’s lyric poetry comprises his 17 epodes and 103 odes in 4 books. The former, which include some of his early work, are on a variety of political and satirical themes, plus a few love poems. Most are written in an iambic metre – a longer line followed by a shorter one – which is known as the epode or ‘after song’. The first three books of odes were written between 33 and 23 BC, and reflect the events of the time. The fourth was published in 15 BC.

Horace’s odes are regarded as his finest works. They are written in a variety of Greek metres whose rules he followed strictly. His other works include Carmen Saeculare, a poem to various gods, commissioned by Augustus to celebrate the Saecular Games in 17 BC; three books of epistles, of which the third is generally known as the literary essay Ars Poetica; and two books of satires. (The Latin word from which our ‘satire’ comes comprised a medley of reflections on social conditions and events.)

Horace appears to have been a bit of a hypochondriac, although he enjoyed his life, his work and the position that work gave him in society to the full. He died only a few months after his patron Maecenas.

Virgil

The Aeneid, the epic of the empire of Rome and of Roman nationalism – for its poetry and poetic sensibility arguably the most influential poem in any language – is unfinished. Moreover, just before he died, its author asked his friends to burn it. Thankfully, literary executors, faced with just this problem throughout history, have usually responded with commendable common sense and regard to posterity, as they did in this case.

Publius Vergilius (or Virgilius) Maro (70–19 BC) was born near Mantua in Cisalpine Gaul. He was educated in Cremona and Milan, and went on to higher education. It seems that he was never particularly fit, which may be one reason why he returned to the family farm to write, only to be deprived of it in 41 BC in the confiscations after the Battle of Philippi. He appealed, and was reinstated on the orders of Octavian, but soon afterwards he left Mantua for good. In 37 BC he published his first major work, a series of bucolic episodes (the Eclogues) loosely based on a similar composition of the Hellenistic pastoral poet Theocritus (c. 310–c. 250 BC).

Maecenas then encouraged Virgil to complete four books of didactic verse about farming and the country year called the Georgics, on which he spent the next seven years. Though these also show Greek influences, the agricultural activities (corn-growing, viticulture, cattle-breeding, beekeeping) are Italian and the message is both topical and nationalistic, with its emphasis on traditional agricultural industries, on a return to the old forms of worship, and on cooperative working for a profitable future.

By this time Octavian was emperor in all but title and name. He felt that an epic poem about his own achievements was called for, and on his behalf Maecenas approached several writers, who turned down the assignment because epic was not their style. Virgil accepted it, but on his own terms. He knew what he wanted to do and saw this as the means to achieve it. He worked on his epic of the mythological antecedents of Rome until his death eleven years later, by which time he had composed some 10,000 lines. The emperor frequently asked for a progress report and, apparently, was not disappointed with either the pace or the product.

In the year 19 BC, Virgil met Augustus in Athens and, instead of going on a tour of Greece and the East as he had intended, accompanied him back to Rome. He caught a fever on the way and died a few days after landing at Brundisium. He was unmarried and, largely thanks to his patrons, a comparatively rich man.

Virgil always wrote in hexameters. The Aeneid is unfinished in that it awaited final revision and polishing, but the story is complete and ends with a dramatic climax. Turnus, king of the Rutuli, stakes everything on single combat with Aeneas. They fight and Turnus is wounded. Aeneas is about to spare him when he spots on his opponent’s shoulder the belt of his dead ally and friend, Pallas, which Turnus has clearly stripped from the corpse. Aeneas, in terrible anger, kills him.

The story of the Aeneid is a deliberate continuation of Homer’s Iliad, to stress the connection between Rome and the heroes of Troy, with strong echoes of the wanderings of Odysseus which are described in the Odyssey. The gods’ continuous intervention and their periodic bickering over which of their favourite mortals shall triumph are in tune with the traditional notions to which Augustus wanted his people to return.

Elegiac poetry: Propertius and Ovid

Sextus Propertius (c. 50–c. 15 BC) was born in Umbria. His father died when he was a child, and his mother sent him to Rome to be educated in the law. Instead he turned to literature and published his first book of elegies in about 26 BC. Most of his poems describe his love for Cynthia, who in real life was called Hostia and appears to have been a freedwoman and a courtesan. Much of Propertius’ verse is peppered with academic allusions and pervaded with melancholy, but the emotions read as though they are sincerely expressed.

Publius Ovidius Naso (43 BC–AD 18) was born at Sulmo, in the mountains east of Rome, of an ancient equestrian family. Destined for a political career, he studied rhetoric and law, and was married at about sixteen, but he divorced shortly afterwards. He held minor legal and administrative posts in the civil service, but abandoned politics for poetry in about 16 BC, when he married again. His wife died two years later, after giving birth to a daughter.

Ovid combined his pursuits of poetry and pleasure in Amores (Love Poems) and Ars Amatoria (The Art of Love). These were not so much erotic as irresponsible in that they appeared to condone adultery, which under Augustan law was a public offence, and for which Augustus banished his own daughter, Julia, in 2 BC. Ars Amatoria was published the following year. In AD 8, Augustus’ granddaughter Julia followed her mother into exile for the same reason. And in that same year Ovid was banished to a bleak place called Tomi, on the west coast of the Black Sea.

Ovid says that the reasons for his banishment were ‘a poem’ (presumably Ars Amatoria, though it had been published some years earlier) and ‘an error’. The error may have had something to do with the younger Julia, or possibly someone disclosed a scandal about Ovid and her mother. Whatever caused his banishment, Ovid had to go, and Ars Amatoria was banned from Rome’s three public libraries. He was never called back, even after the death of Augustus, but he kept writing, sadly and ultimately resignedly. His third wife, a young widow with a daughter, remained devoted to him to the last.

Ovid aimed to use elegiac couplets to amuse the reader, which he did as much by verbal effects and ingenious and delicate deployment of his verse form as by what he said. The fifteen books of Metamorphoses (Transformations), his most enduring and influential work, are written in hexameters. This vast collection of linked myths and legends was widely drawn upon by later Roman and European writers.

Epigram and satire: Martial and Juvenal

An epigram is a Greek term meaning ‘inscription’, often in verse, on a tombstone or accompanying an offering. In the hands of Martial it became the medium for short, pointed, witty sayings about people and the hazards of daily and social life, usually in elegiacs, but also in hendecasyllabics and other metres.

Marcus Valerius Martialis (c. AD 40–104) was a Spaniard from Bilbilis who arrived in Rome in AD 64 and was taken up by his literary fellow-countrymen Seneca and his nephew Lucan, until they were purged by Nero. Initially Martial scraped a living by writing verses for any occasion, even on the labels for gifts presented to guests at parties. Ultimately he published several books of verse, and ended up owning a farm in the country as well as a house in Rome. He was a hack, a parasite and, when it suited his interests, as it did when he wrote about Domitian, an unctuous flatterer. However, he was almost always witty, if often coarse, and frequently poetic, while pioneering a form of literature that has had many exponents ever since.

One of Martial’s friends was Decimus Junius Juvenalis (c. AD 65–c. AD 140), the most graphic of the Roman satirists and the last of the classical poets of Rome. As far as we can tell, he was born in Aquinum, the son of a well-to-do Spanish freedman. He may have served as commander of an auxiliary cohort in Britain and possibly held civic offices in his home town before trying to make a living in Rome by public speaking. At some point during the reign of Domitian, he seems to have been exiled for a while to Egypt, undoubtedly for saying or writing something offensive to the emperor, but not sufficiently offensive to be executed for it.

The sixteen satires that we have were published between about AD 110 and 130, in the reigns of Trajan and Hadrian. Written in hexameters, they attack various social targets, including homosexuals, living conditions in Rome, women, extravagance, human parasites and vanity, while moralizing on such subjects as learning, guilty consciences, parental example and the treatment of civilians by the military. They contain plenty of sarcasm, invective and broad humour.

The novel: Petronius and Apuleius

The romance in prose was a literary form used by the Greeks from the first to the third century AD. In the hands of Petronius and Apuleius, in particular, the Roman novel took on a different aspect. Hovering between prose fiction and satire is the Satyricon of Gaius Petronius (d. AD 66), also known as Petronius Arbiter, from his job-title as organizer of Nero’s personal revels. It is also the original picaresque novel, a kind of bisexual odyssey of two men and their boy around the towns of southern Italy. We only have fragments, the best known of which is ‘Trimalchio’s Dinner-Party’, which splendidly reflects the manners and mores of the Roman nouveaux riches.

Petronius, a victim of one of Nero’s periodic purges, bled himself to death while conversing, eating and even sleeping, having committed to paper, and sent to Nero, a classified list of the emperor’s most perverted sexual acts.

Lucius Apuleius was born in about AD 125 at Madaura in North Africa. According to his own account, he married a rich widow much older than himself, and was then accused by her family of sorcery. He was certainly very interested in magic and its effects, but he conducted his own defence and was acquitted.

His novel Metamorphoses, better known as The Golden Ass, is a rollicking tale of the supernatural, told in the first person. Lucius tries to dabble in magic, is given the wrong ointment by the serving-maid who is also his bed-mate, and is turned into an ass. Several good stories are spliced into the action of The Golden Ass, including an excellent version of the legend of Cupid and Psyche. The conversion of Lucius to the cult of Isis after his re-transformation into human form gives the ending a religious significance as well as a narrative twist. Apuleius himself became a priest of Osiris and Isis. He was also a devotee of Asclepius, god of medicine, which he seems to have found compatible with organizing gladiatorial shows for the province of Africa.

Historians: Caesar, Livy, Tacitus, Suetonius

The original Roman records, with the names of the principal officials for each year, were inscribed on white tablets in the keeping of the pontifex maximus and displayed to the public.

The earliest surviving account of contemporary events is Julius Caesar’s seven-book record of his campaigns in Gaul, De Bello Gallico (Gallic War). (An eighth book was written by Aulus Hirtius (d. 43 BC).) Objective in that he mentions but does not dwell on his failures, and written in the third person, it is a distinguished general’s account of his actions in war in a clear no-nonsense style. The arts of the orator and politician are more evident in De Bello Civile (Civil War), in which by careful selection of facts and linguistic legerdemain he attempts to put the blame squarely on his opponents.

Titus Livius (59 BC–AD 17) was born and died in Padua, lived most of his life in Rome, had two children, and was a close acquaintance of Augustus and Claudius. That is almost all we know about this great writer and moderately good historian. Livy’s full history of Rome – from Aeneas to 9 BC – comprised 142 books, of which we have 35, plus synopses of the others.

Livy was a popular historian in that he concentrated on narrative and character, and paid particular attention to the composition of the speeches he put into the mouths of his protagonists. He drew on a wide range of sources and traditions without being particularly concerned about accuracy, though he makes up for vagueness about geographical and military details with his sense of drama. The truth he sought was that which would in turn reflect gloriously on the Rome of the present.

Books of the Annals of Tacitus survive covering the reigns of Tiberius, Claudius and Nero. We have just over four books of the Histories, describing the years AD 69–70.

Cornelius Tacitus (c. AD 55–c. AD 117) was a public figure in his own right as well as being the son-in-law of Agricola. He was a senator, consul in AD 97, and governor of Asia in AD 112. He was an excellent public speaker, and published a book on oratory when he was in his twenties. He also wrote a short biography of Agricola, and Germania, a report on the land and people of Germany. He was a witty writer as well as an incisive literary stylist, a shrewd observer and commentator, and an upholder of the ancient virtues of his nation.

Ammianus Marcellinus (c. AD 330– c. AD 393) wrote a continuation of Tacitus’ Histories in thirty-one books, of which we have eighteen, covering the years AD 353–378.

The family of Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus (c. AD 70–c. AD 140) probably came from Algiers. They were of equestrian class, and his father had a distinguished military career. Suetonius himself held a succession of posts in the imperial court, becoming director of imperial libraries and then chief of Hadrian’s personal secretariat, which gave him access to archive material on earlier reigns. His series of biographies of the twelve Caesars is the only one of his many biographical and antiquarian works to have survived intact. He was, with Plutarch, the originator of the modern biography.

Philosophy and science: Seneca and Pliny the Elder

Lucius Annaeus Seneca (4 BC–AD 65) was the tutor, and victim, of Nero, and the first patron of Martial. The second son of Seneca the Elder, he was born in Corduba, Spain, into a brilliant family. He arrived in Rome at an early age and was influenced by the Stoics, whose philosophy ran counter to that of the Epicureans in that its keynote was ‘duty’ rather than ‘pleasure’. It also allowed for the existence of an overall spiritual intelligence.

In his philosophical writings, of which twelve dialogues and 124 epistles to his friend Lucilius survive, Seneca comes across as a moral philosopher whose aim was to live correctly through the exercise of reason. Naturales Quaestiones (Scientific Investigations) is an examination of natural phenomena from the point of view of a Stoic philosopher.

We also have ten of Seneca’s verse tragedies. These are solid, lyrical and bleak in their tragic vision which allows no escape from evil or defence against the brutality of fate. From his example, Elizabethan and Jacobean dramatists took the five-act structure and also the cast of secondary characters who serve to keep the action moving, to report on events off stage, and to elicit private thoughts (especially those of the heroine through a confidante). The violent and gruesome Thyestes is the archetypal revenge tragedy.

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23–79), Pliny the Elder, was concerned with natural phenomena throughout his life. He was born into a wealthy family at Como, practised law in Rome, and saw military service through several postings. Between the accession of Vespasian in AD 70 and his untimely death nine years later he held several senior government posts and wrote thirty books of Roman history as well as the thirty-seven books of his Natural History.

Natural History, his only surviving work, covers many subjects, including physics, geography, ethnology, physiology, zoology, botany, medicine and metallurgy, with frequent digressions into anything else that interested him at the time. He drew his material from many written sources – when he was not reading something himself or writing, he had someone read aloud to him – as well as from his own observations.

He always carried a notebook, as he did when venturing from the naval station at Misenum, of which he was the commander, to investigate the eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79. He landed on the beach, taking notes all the time, and was either asphyxiated by the fumes or buried under falling rocks.

Letter-writers: Cicero and Pliny the Younger

A number of Cicero’s speeches and several of his philosophical works – in which field he established a tradition of Roman writing – survive. They are masterpieces of style and rhetoric. To the student of Roman life, however, the four collections of his letters – to his Brother Quintus, a soldier and provincial governor who also died in the proscriptions; to his friends; to Brutus, the conspirator; and to Atticus, who was his closest friend and confidant – edited shortly after his murder in 43 BC, are of even greater and more immediate interest.

![<em>Aureus</em> of Brutus, 42 BC, depicts his head surrounded by a laurel wreath, with the inscription: BRVTVS IMP[ERATOR] (‘Brutus, victorious commander’). (© CNG Coins)](https://s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3-euw1-ap-pe-ws4-cws-documents.ri-prod/9781138543898/intro-images/chapter-8/8.48.jpg)

Some of Cicero’s letters were undoubtedly intended for ultimate publication, but, taken as a whole, they are refreshingly revealing about himself and his day-to-day existence during the last twenty-five years of his life.

Gaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus (AD 61–c. AD 113), known as Pliny the Younger to distinguish him from his eminent uncle and adoptive father, certainly intended his correspondence for publication, and in his lifetime. He showed early literary promise, and became a distinguished orator, public servant and philanthropist. He endowed a library at Como, a school for children of free-born parents and a public baths, while the interest on an even larger sum was left in his will for the benefit of a hundred freedmen and for an annual public banquet.

Pliny’s letters range over many private and public topics: of particular interest is his first-hand account of the eruption of Vesuvius (6.16 and 20), the description of his villa (2.17), news of a haunted house in Athens (7.27) and of a tame dolphin (9.33), and his official report on the Christians to Trajan (10.97), in his capacity as governor of Bithynia, and his request for a policy decision on how to deal with them.