Introduction

Roman religion & mythology

‘First thing of all is to revere the gods, especially Ceres: to her greatness dedicate the yearly rites … Let no one put his sickle to the corn without a wreath of oak-leaves on his head, or giving Ceres an impromptu dance, and singing verses to her bounteousness.’

(Virgil, Georgics 1.338–350)

Insofar as the Romans had a religion of their own, it was not based on any central belief, but on a mixture of fragmented rituals, superstitions and traditions which they collected over the years from a number of sources. To them, religious faith was less a spiritual experience than a contractual relationship between mankind and the forces that were believed to control people’s existence and well-being.

The result was a state cult whose significant influence on political and military events outlasted the republic, and a private concern, in which the head of the family supervised the domestic rituals and prayers in the same way as the elected representatives of the people performed the public ceremonials.

Roman divinities

Many of the gods and goddesses worshipped by the Romans were borrowed from the Greeks, or had their equivalents in Greek mythology. Some of these came by way of the Etruscans or the tribes of Latium.

The Diana to whom Servius Tullius built the temple on the Aventine Hill was identified with the Greek Artemis, but some of the rites attached to her at Aricia, the centre from which he transferred her worship, went back to an even mistier past. The Romans inherited their preoccupation with examining every natural phenomenon for what it might foretell from the Etruscans.

The Etruscans employed three main kinds of divination:

- Divining the future from examining the entrails of victims sacrificed at the altar – the liver was of particular significance.

- Observing and explaining the meaning of lightning and advising on how sinister predictions might be averted.

- Interpreting any unusual phenomena and taking necessary action.

Many early societies practised animism, the belief that natural and physical objects are endowed with mystical properties. Alongside an appreciation of the divinity that resided in gods and goddesses with human attributes and human personalities, the Romans invested trees, springs, caves, lakes, animals and even household furniture with numina (singular numen), meaning the ‘divine will’ or ‘divine powers’ of a deity. Significant gods and goddesses had multiple functions, while minor administrative roles were often undertaken by attendant spirits, known as indigitamenta, into whom the deity projected the numen of that particular activity.

Boundary stones between one person’s property and the next had particular significance. The word for a boundary stone was terminus: there was even a great god Terminus, a massive piece of masonry which stood permanently in the Temple of Jupiter on the Capitoline Hill because it refused to budge even for Jupiter.

Prayer and sacrifice

The contractual relationship between mankind and the gods involved each party in giving, and in turn receiving, services. The Romans believed that powers residing in natural and physical objects had the ability to control the processes of nature, and that man could influence these processes by symbolic action.

The ‘services’ by which Romans hoped to influence the forces that guided their lives were firmly established in rituals – the ritual of prayer and the ritual of offering. In either case the exact performance of the rite was essential: one slip, and you had to go back to the beginning and start again.

Many deities went by a variety of names. For instance, Juno, consort of Jupiter, had more than ten names or surnames for use on special days or in particular circumstances. These included Juno Lucina (Lucina here means ‘Bringing into light’), in her guise as goddess of childbirth, and Juno Moneta (the ‘Mint’), because her temple on the Capitoline Hill housed the state mint, where money was coined and stored.

There were few occasions on which a prayer was deemed inappropriate. Some prayers were realistic and modest, for example the ‘Poet’s Prayer’ of Horace (65–8 BC), which ends: ‘I pray, Apollo, let me be content with what I have, enjoy good health and clarity of mind, and in a dignified old age retain the power of verse’ (Odes 1.31). This, however, was as near as any Roman usually got to praying for anything other than material benefits.

Prayer was almost invariably accompanied by some form of offering or sacrifice. This did not necessarily involve the ritual slaughter of an animal, as long as the offering represented life in some form: it could be millet, cakes made from ears of corn that had been picked a month earlier, fruit, cheese, bowls of wine, or pails of milk.

In the case of a sacrifice, each deity had his or her own preference. The sex of a chosen animal was also significant: male for gods, female for goddesses. So was its colour: white beasts were offered to deities of the upper world, black to those of the underworld, while a red dog was sacrificed to Robigus, symbolizing the destruction of red mildew.

The sacrifice for Mars was usually a combination of an ox, a ram and a boar. On 15 October, however, it had to be a racehorse: in fact, a victorious racehorse. The near-side horse of the winning pair in that day’s chariot race was immediately taken to the altar and slaughtered.

The sacrificial routine was invariably elaborate and messy. The head of the victim was sprinkled with wine and bits of sacred cake made from flour and salt. The victimarius then stunned the animal with an axe or mallet before cutting its throat and disembowelling it to ensure that there was nothing untoward about its entrails. If there was, this was a bad omen and the whole process had to be repeated with a fresh animal until the innards came out right.

The vital organs were burned upon the altar and the carcase cut into pieces and eaten on the spot, or laid aside. Then the priest, wearing something over his face to shut out evil influences from his eyes, would say prayers, speaking under his breath, while a flute was played to drown out any ill-omened noise.

Any unintentional deviation from the prescribed ritual meant not only a new sacrifice but an additional one in expiation of the error. On high occasions, when a replay of the entire ceremony might be an embarrassment, an expiatory sacrifice was performed as a matter of course on the preceding day, to atone for any sin of omission or error that might occur on the day itself.

Gods, goddesses, & spirits

- Annona: Mythical personification of the annual food supply

- Apollo: (Greek) God of healing and prophecy

- Asclepius: (Greek) God of healing

- Attis: (Phrygian) Beloved of Cybele

- Bacchus: (Greek as Dionysus) God of wine.

- Bellona: Goddess of war

- Bona Dea: (‘Good Goddess’) Unnamed spirit whose rites were attended only by women

- Cardea: Household goddess of door hinges

- Castor and Pollux: (Greek: also as Dioscuri) Two legendary heroes

- Ceres: (Identified with Greek Demeter) Goddess of agriculture

- Consus: God of the granary

- Cybele: (Phrygian) See Magna Mater

- Diana: (Identified with Greek Artemis) Goddess of light; also unity of peoples

- Dis: (Greek as Pluto) God of the underworld

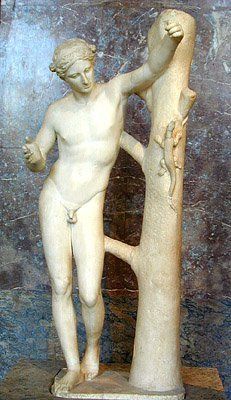

- Faunus: (Identified with Greek Pan) God of fertility

- Flora: Goddess of fertility and flowers

- Forculus: Household god of doors

- Fortuna: (also Fors, Fors Fortuna) Goddess of good luck

- Genius: Protecting spirit

- Hercules: (Greek: Herakles) God of victory and commercial enterprises

- Isis: (Egyptian) Goddess of the earth

- Janus: God of doorways

- Juno: (Identified with Greek Hera) Goddess of women

- Jupiter: (Also Jove; identified with Greek Zeus) God of the heavens

- Juturna: Goddess of fountains

- Lar (plural Lares): Spirit of the household (see Figure 5.21)

- Larvae (or Lemures): Mischievous spirits of the dead

- Liber: God of fertility and vine-growing (= Bacchus)

- Libitina: Goddess of the dead

- Limentinus: Household god of the threshold

- Magna Mater: (Phrygian as Cybele) ‘Great Mother’, goddess of nature

- Manes: Spirits of the dead

- Mars: God of war

- Mercury: (Identified with Greek Hermes) God of merchants

- Minerva: (Identified with Greek Athena) Goddess of crafts and industry

- Mithras: (Persian) God of light

- Neptune: (Identified with Greek Poseidon) God of the sea

- Nundina: Presiding goddess at the purification and naming of children

- Ops: God of the wealth of the harvest

- Osiris: (Egyptian) Consort of Isis

- Pales: God/goddess of shepherds

- Penates: Household spirits of the store cupboard

- Picumnus and Pilumnus: Agricultural gods associated with childbirth

- Pomona: Goddess of fruit

- Portunus: God of harbours

- Priapus: God of fertility in gardens and flocks

- Quirinus: State god under whose name Romulus was worshipped

- Robigus: God of mildew

- Sabazius: (Phrygian) God of vegetation

- Salus: God of health

- Saturn: (Identified with Greek Cronos) God of sowing

- Serapis: (Egyptian) God of the sky

- Silvanus: God of the woods and fields

- Sol: God of the sun

- Tellus: Goddess of the earth

- Terminus: God of property boundaries

- Venus: (Identified with Greek Aphrodite) Goddess of love

- Vertumnus (also Vortumnus): God of orchards

- Vesta (Identified with Greek Hestia): Goddess of the hearth

- Volturnus: God of the river Tiber

- Vulcan: God of fire

Omens

A sibyl was a Greek prophetess. The story goes that one of her kind offered to Tarquinius Superbus a collection of prophecies and warnings in the form of nine books at a high price. When he refused, she threw three of them into the fire and offered him the remaining six at the original price for all nine. He refused again, so she burned three more and offered him the rest, still at the same price. This time he bought them. The Sibylline Books were consulted on the orders of the Senate at times of crisis and calamity, in order to learn how the wrath of the gods might be allayed. They were accidentally burned in 83 BC, and envoys were sent all round the known world to collect a set of similar utterances. Augustus had the new collection put in the Temple of Apollo on the Palatine Hill, where it remained until it was destroyed in the fifth century AD.

Disasters were seen by the Romans as manifestations of divine disapproval, and unusual phenomena as portents of catastrophe. The taking of auspices – the literal meaning of which is ‘signs from birds’ – was a standard procedure before any state activity.

An official augur, who was present on such occasions merely as a consultant, marked out and prepared the statutory square measure of ground and then handed over to the state official who was to perform the ritual. He took up his position and observed the flights of any birds he could see – their species, height, position, speed and direction of flight. If there was any doubt about the interpretation of what the official saw, the augur was called upon to advise.

Armies took with them a portable auspices kit, consisting of a cage of sacred chickens, in front of which pieces of cake were placed to see what would happen. It was a bad sign if they refused to eat, but good if they ate the cake and let fragments of grain fall from their beaks. Public business was frequently interrupted so that the omens could be consulted. A law passed by an assembly or an election could be declared invalid if the correct procedure had not been carried out.

There was a distinction between signs that were solicited and those which appeared without invitation. The more startling or unexpected the sign – for instance, a flash of lightning or an epileptic fit on the part of a member of an assembly – the more seriously it was taken.

Worship in the home

Two national deities had their place in private worship too: Vesta, goddess of the fire and the hearth, and Janus, the god of doorways. Vesta was particularly important to women of the household, for the hearth was where food was prepared and cooked, and beside it the meal was eaten. Prayers were said to the goddess every day, and during a meal a portion of food might be thrown into the fire as an offering, and to seek omens from the way in which it burned.

Janus, who gave his name to the month of January, is often depicted with two faces, one looking in each direction. It has been suggested that this represents the opening and closing of a door, going in and coming out, or viewing (and thus guarding) both the inside and the outside of a house.

The particular gods of the household were its lares and penates.

The lares (one of them was designated lar familiaris or ‘family spirit’ and was special to that household) were supposed to be the spirits of dead ancestors, and they had their own cupboard which they inhabited in the form of tiny statuettes. Daily prayers and offerings were made to them. The penates looked after the larder, its contents and their replenishment, and also had their own cupboard. The statuettes of the penates were taken out and put on the table at mealtimes. When the family moved, its lares and penates went with them.

In addition, each household had its genius, whose image was a snake. Genius might be described as a ‘spirit of manhood’, since it was supposed to give a man the power of generation, and its sphere of influence was the marriage-bed. The household genius was especially honoured on the birthday of the head of the family.

Births and deaths had their special rituals. Juno Lucina was the main deity of childbirth, but other spirits watched over the embryonic child and its mother from the moment of conception to the birth itself. Immediately after the birth, a sacred meal was offered to Picumnus and Pilumnus, two jolly rustic deities, for whom a made-up bed was kept in some conjugal bedrooms. A positive string of child-development deities watched over the baby’s breast-feeding, bones, posture, drinking, eating and talking, including its accent.

On the ninth day after the birth of a boy (or the eighth for a girl), the ceremony of purification and naming was enacted. Free-born children received an amulet – gold for a child of the rich; bronze or merely leather for poorer families – which a girl would wear until her marriage, and a boy until he exchanged his toga praetexta, the robe of a child that was also worn by girls, for the toga virilis, the garb of a man, between the ages of fourteen and seventeen.

There were several ways of celebrating a marriage, of which the simplest involved the consent of both parties, without any rites or ceremony. Each of the other three gave the husband legal power over his wife:

- By cohabiting for a year without the woman being absent for a total of three nights.

- By a symbolic form of purchase, in the presence of a holder of a pair of scales and five witnesses.

- By full ritual, in the presence of the pontifex maximus.

After the second century AD a different kind of ritual emerged, which began with a formal betrothal, at which the prospective bride slipped a gold ring on to the finger now known as the ‘wedding finger’ in the presence of the guests. For the marriage ceremony itself she wore a veil of orange-red (the flamen), surmounted by a simple wreath of blossom.

While a spirit of some kind watched over a person at most times and on most occasions from conception to death, at the actual moment of death there was none. The religious element in the funeral rites was directed towards a symbolic purification of the survivors. Once the corpse was entombed or buried – and even in the case of cremation one bone was preserved and put in the ground – its own spirit joined all those other spirits of the dead, which were known collectively as manes and required regular worship and appeasement. There were also mischievous spirits of the dead, known as larvae or lemures.

Worship in the fields

To the countryman, the natural world teemed with religious significance. The fields, orchards, vineyards, springs and woods all had their attendant deities or spirits. Silvanus, god of the woods and fields, guarded the boundary between farmland and forest, and the estate regularly had to be protected from natural and supernatural hazards by lustration, the ritual of purification involving sacrifice and a solemn procession around its perimeter.

The farmer’s annual round began in the spring, which the original Roman calendar reflected by its year beginning on 15 March. The establishment of what is now New Year’s Day in Christian countries at 1 January was for sheer administrative convenience. In 153 BC, in order to enable the arrival in Spain of the incoming consul to coincide with the start of the campaigning season, the beginning of his term of office, and thus of the year, was advanced to 1 January, and there it remained.

The first celebration of the country year was the Liberalia on 17 March, in honour of Liber, god of fertility in the fields and vineyards. It was also the traditional date on which a teenage boy abandoned his toga praetexta for the toga virilis.

The latter part of April was a riot of festivals, each with its own special significance. At the Fordicia on 15 April, pregnant cows were sacrificed to the earth-goddess Tellus.

In Rome itself, there was a macabre finale to the festival of Ceres, when flaming torches were attached to the tails of foxes, which were let loose in the space below the Capitoline Hill that later became the Circus Maximus. After the Vinalia Rustica, probably a drunken revel to celebrate the end of winter, and the sacrifice of the red dog to Robigus, god of mildew, April closed with the Floralia, ostensibly to petition for the healthy blossoming of the season’s flowers. It lasted from 28 April to 3 May and appears to have been celebrated with the greatest jollity and licence.

As the crops ripened, there were several rites of a more serious nature, including the movable feast of the Ambarvalia, during which the ritual lustration was renewed and the farmer sacrificed a pig, a sheep and an ox, together with items from the previous harvest and the first fruits of the new one.

When the corn was cut in August, there were celebrations to Consus, god of the granary, and Ops, god of harvest wealth, and a further Vinalia Rustica.

The real festival of thanksgiving for the wine crop, the Meditrinalia, was observed on 11 October. Sowing took place in December, during which there were repeats of the festivals of Consus and Ops. The Saturnalia was on 17 December. This festival was observed in the country as a genuine celebration of seed-time; in towns it was a longer celebration which embodied some of the secular traditions later associated with Christmas, including holidays from school, the lighting of candles, the exchange of gifts, the mingling of household staff with the family, and the wearing of party hats.

The religion of the state

The religion of the Roman state reflected the ways of private worship, while retaining traditions from the period of the kings. Under the nominal direction of the pontifex maximus, administrative and ritualistic matters were the responsibility of four colleges, whose members were usually appointed or elected from the ranks of politicians and held office for life.

The members of the pontifical college, the senior body, were the rex sacrorum, pontifices, flamines and the Vestal Virgins. Rex sacrorum (king of religious rites) was an office created under the early republic to maintain the tradition of royal authority over religious matters. Though in later times the holder of this office still took precedence at religious ceremonies, it had by then become largely an honorary position.

The sixteen pontifices (priests) were the chief administrators and organizers of the religious affairs of the state, and authorities on procedure and matters of the calendar and festivals.

The flamines were priests of particular gods: three for the major gods (Jupiter, Mars and Quirinus) and twelve for the lesser ones. These specialists had the technical knowledge of the worship of the particular deity to whom, and to whose temple, they were attached, and performed the daily sacrifice to each.

The flamen dialis was the most important of the flamines. His life was hedged around with taboos and hazards: he was not allowed to ride a horse, touch (or even mention) a nanny-goat, uncooked meat, ivy or beans, or go without his official cap, even indoors.

The six Vestal Virgins were chosen from ancient patrician families at an early age to serve at the Temple of Vesta. They normally served ten years as novices, the next ten performing duties, and a further ten teaching novices. They had their own convent near the Forum, and their duties included guarding the sacred fire in the temple, performing the rituals of worship, and baking the salt cake which was used during various festivals throughout the year. Each Vestal Virgin enjoyed considerable prestige.

The fifteen members of the college of augurs exercised great learning, and presumably also diplomacy, in the interpretation of omens in public and private life, and acted as consultants in cases of doubt. The members of the college of quindecemviri sacris faciundis (‘fifteen for special religious duties’) were the keepers of the Sibylline Books, which they consulted and interpreted when requested to do so, and ensured that any prescribed actions were carried out properly. They also had responsibility for supervising the worship of any foreign deity which was introduced into the religion of the state from time to time, usually on the recommendation of the Sibylline Books.

One such deity was Cybele, the Phrygian goddess of nature, whose presence in Rome in the form of a sacred slab of black meteoric rock was recommended in 204 BC after it had rained stones more often than usual. The cult itself, symbolized by noisy processions of attendant eunuch priests and flagellants, was exotic and extreme, in direct contrast to the stately, methodical practices of state religion, and Roman citizens were discouraged from participating in its rites until the time of Claudius. However, the annual public games in honour of Cybele, the ‘Great Mother’, were held in considerable style from 4 to 10 April, and were preceded by a ceremonial washing and polishing of her stone by members of the college.

The three (later seven) office-holders of the college of epulones (‘banqueting managers’) belonged to the smallest and most junior of the four colleges. It was founded in 196 BC, presumably as a result of the amount of organization required to put on the official feasts which had become integral parts of the major festivals and games.

The earliest state religious festivals were celebrated with games, such as the very first one recorded at Rome, the festival to Consus at which the Sabine women were kidnapped. The Consualia, traditionally celebrated in the city on 21 August, was also the equivalent of Derby Day – the main event of the chariot-racing calendar.

Religious festivals could be grave as well as joyful. February saw both kinds. During the nine days of the Parentilia, during which the family dead were worshipped, state officials did no business, temples were closed, and marriages were forbidden.

In complete contrast was the ancient Lupercalia, at which the deity honoured was probably Faunus, god of fertility, but the proceedings reflected the origins of Rome itself.The rites started in the cave where Romulus and Remus were supposed to have been suckled by the wolf. Several goats and a dog were sacrificed, and the blood was smeared over two youths from noble families. The pair then ran a prescribed cross-country course, wearing goatskins and carrying strips of hide, with which they whipped people as they passed. The blows were supposed to promote fertility.

During the festivities for Mars from 1 to 19 March, two teams each of twelve celebrants known as salii (‘jumpers’) put on the helmets, uniform and armour of Bronze Age warriors and leapt through the streets, chanting and beating their shields. Each night they rested, and feasted, at a prearranged hostelry or private house.

The festival of Vesta in June was a more sedate and dignified affair. For a week, the storehouse of treasures in the temple was open to married women, who came barefoot with offerings of food. On 15 June the Vestal Virgins swept out the place, and public business, which had been suspended during the festival, resumed. As an extra touch, on 9 June mill-donkeys were hung with garlands of violets, decorated with loaves of bread, and given the day off.

There was not a month in the Roman calendar which did not have its religious festivals. August, the sixth month of the old calendar, hosted, in addition to the Consualia, festivals to Hercules (god not just of victory but of enterprise in business), Portunus (god of harbours), Vulcan (god of fire) and Volturnus (god of the Tiber). This was also the month when the ancient festival of Diana was remembered on the Aventine.

That January should find itself the first month in the revised calendar was entirely appropriate. Janus, who gave his name to it, was a god unique to the Romans: he had no equivalent in any other mythology. He was the god of beginnings as well as of the door. He began the year, and received the first state sacrifice of the year at the Agoria on 9 January. Moreover, the first hour of the day was sacred to him, and his name took precedence over all others in prayers.

The gates of his temple in the north-east corner of the Forum were (it is said on the orders of Numa) kept wide open in times of war. According to Livy (59 BC–AD 17), this meant that they were closed only twice in the succeeding seven centuries.

Cults

The survival of a religious faith depends on a continual renewal and reaffirmation of its beliefs, and sometimes on adapting its ritual to changes in social conditions and attitudes. To the Romans, the observance of religious rites was a public duty rather than a private impulse. Their beliefs were founded on a variety of unconnected and often inconsistent mythological traditions. Without any basic creed to counter, foreign religions made inroads into a society whose class structure was being blurred and whose constitution was being changed by the increased presence of freed slaves and incomers from abroad.

The brilliance of some of the major foreign cults had considerable attraction for those brought up on homespun deities of the hearth and the fields. The worship of Mithras, the emissary of light who symbolized the fight to disseminate life-giving forces in the face of the powers of darkness and disorder, reached Rome from Persia in the first century AD and enjoyed particular support within the army.

Worship of the Egyptian goddess Isis came to Rome in the early years of the first century BC. It was just one of the cults known as ‘mysteries’, all of which were Greek in origin.

The mysteries were cults whose rituals were known only to initiates, who appear to have guarded their secrets closely – as well they might, considering the restrictions on any worship which conflicted with that of the state. However, in addition to literary allusions, some fascinating glimpses of the cults of Isis and Bacchus – in the form of wall paintings uncovered at and near Pompeii – were preserved by the eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79.

Traditional beliefs were further eroded in the face of a Greek school of philosophy, the Stoics, who championed the notion of a single deity. They were also affected by the Jewish diaspora.

A Jewish force assisted Julius Caesar in Egypt during his campaign there in 48 BC, and in return he granted the Jews privileges which included the freedom of worship in Rome itself. A form of semi-Judaism became fashionable, especially among women; one did not have to be a full convert to attend synagogue services. Hadrian, who became emperor in AD 117, tried to eradicate Judaism by forbidding all Jewish practices. However, his successor Antoninus, in about AD 138, rescinded Hadrian’s legislation, with the significant exception of circumcision, which was restricted to those of the Jewish faith.

More than a century earlier, Augustus, as part of his national morale-boosting campaign, had reaffirmed the traditional forms of worship. He restored eighty-two temples in and around Rome (it is claimed all in the space of one year), and in 12 BC had himself appointed pontifex maximus, a post which thereafter was restricted to emperors. Thus, the head of state was once again also the head of religious affairs.

Augustus promoted the god Apollo, with whom his own family was said to have special affinities, to the status of a major deity, and dedicated a magnificent new temple to him on a site on the Palatine Hill which was his personal property.

He did not take the connection between religion and rule so far as to allow himself to be officially regarded as a god in his own lifetime, but he prepared the way to deification after his death by confirming the divinity of his adoptive father Julius Caesar and dedicating a temple to him.

While Augustus was happy to accept the worship of non-Romans, provided that his name was coupled with that of Rome (or Roma, the goddess who personified Rome), his deification enabled the proliferation throughout the empire of Rome’s most potent export: the imperial cult, or emperor worship. In this way, the loyalty of inhabitants of the provinces of Rome could be focused on an individual rather than on a concept of government. Even one of the most pragmatic of Augustus’ successors, Vespasian, dedicated a new temple to the ‘divine’ Claudius; he also encouraged the establishment of emperor worship in the provinces of Baetica (south-east Spain), Gallia Narbonensis, and Africa, to strengthen ties between their inhabitants and his family.

Emperor worship bound together the largely Hellenized eastern empire and the predominantly Celtic and Germanic provinces of the West. In the latter, however, traditional Roman deities infiltrated local religions, which were often reinterpreted along Roman lines. However, Roman interference occurred only in cases of obnoxious practices, such as human sacrifice, or for political reasons. Except in army camps and Roman colonies, the Roman religion and attendant culture had little impact on the Hellenized East, where the responsibility for temples and their priesthoods was left largely to the local authorities.

In about AD 30, in the reign of Tiberius, a young Jewish thinker and teacher, the son of a carpenter from Nazareth, was executed in Jerusalem under Roman law. His name was Jesus, and he was held to be the Messiah (the ‘chosen one’). While his death was hardly noticed by Roman historians, with hindsight it is not so remarkable that the first adherents to a new and personalized religion, which had its roots and basic teachings in the most intellectually acceptable faith of the times, should have succeeded in spreading its message throughout the ancient world.

During the second century AD Christians were persecuted for their beliefs largely because these did not allow them to give the statutory reverence to images of gods and emperors, and because their act of worship transgressed Trajan’s edict forbidding meetings of secret societies. To the government, it was civil disobedience; to the Christians themselves, it was a suppression of their freedom of worship.