Introduction

The Roman empire: zenith and decline (AD 96–330)

‘Their united reigns are possibly the only period in history in which the happiness of a great people was the sole object of government.’

(Edward Gibbon, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, 1.3)

After the extinction of the Julio-Claudian and Flavian dynasties, a consistent policy of rule and dynastic succession were never again effectively combined. Able men could, however, make their way to the top and, if allowed to reign without internecine upheaval, could do so with as much insight and flair as any of the Caesars, and with more than most.

The ‘five good emperors’ (AD 96–180)

When for the first time the Senate made its own choice of emperor and appointed Nerva, its members chose well; and equal perspicacity attended the appointment of his four successors. All four came from families which had long before settled out of Italy: those of Trajan, Hadrian and Marcus Aurelius in Spain, and that of Antoninus in Gaul. Nerva assured himself of the support of the military by adopting as his son and joint ruler the commander in Upper Germany, Marcus Ulpius Trajanus (Trajan), and set a significant precedent by nominating him as his successor.

Trajan established at once that the Senate would be kept informed about what was going on, and that the sovereign right to rule was compatible with freedom for those who were ruled. He was a brilliant general, but also a good employer, of which there is evidence in the correspondence between him and Pliny the Younger, when the latter was governor of Bithynia.

Trajan was determined to subdue the Parthians, who occupied great tracts of desert land south of the Caspian Sea. He scored some notable victories and occupied some of the Parthian lands, but fell ill and died on his way back to Rome in AD 117, having left his forty-one-year-old chief-of-staff, Publius Aelius Hadrianus (Hadrian), who was also his ward, in charge of the situation in the east.

Hadrian claimed that Trajan had adopted him on his deathbed, but in any case he had already been acclaimed as emperor by the army in the east, and the Senate had little choice but to confirm him in the post or risk civil war. Hadrian settled down to restore general order throughout the empire and to consolidate the administration at home. The Roman empire was a collection of territories occupied by Roman troops and administered by Roman citizens according to Roman law. Central government from Rome was well-nigh impossible, and provincial governors were largely left to their own devices. Hadrian, however, travelled tirelessly not only to all the provinces in the empire but along most of their outer confines.

He was also a man of wide learning who, it was said, spoke Greek more fluently than Latin. He was a patron of art, literature and education, and a benefactor of the needy poor. His liberal-mindedness did not, however, extend to the Jews, whom he provoked into renewed revolt by forbidding Jewish practices, including circumcision, and by proposing a shrine to Jupiter on the site in Jerusalem where the ancient Jewish Temple had stood before it was destroyed by Titus.

Hadrian died in AD 138. After his first choice as successor died, just before his own death Hadrian had adopted in his place the eminent senator Antoninus, then in his early fifties. At the same time he restricted the choice of the next emperor after Antoninus to either Lucius Verus (AD 130–169), son of his original nominee, or Antoninus’ own nephew, Marcus Aurelius Antoninus.

The twenty-three-year reign of Antoninus, who was granted the surnamed ‘Pius’ by the Senate, was remarkable for its lack of incident, perhaps because with the reports available to him of Hadrian’s globe-trotting missions, he was able to spend most of his time at the centre of government in Rome. He made one or two adjustments to the frontiers of the empire, most notably in Britain, where a fortified sixty-kilometre turf wall was built right across the Clyde–Forth isthmus, some way north of Hadrian’s Wall. However, it seems to have been abandoned, perhaps dismantled, in about AD 165. Hadrian’s Wall then once again became the most northerly frontier of the empire until about AD 400, when the Romans withdrew from Britain.

At the end of his peaceful reign Antoninus died in his bed. By contrast, Marcus Aurelius, the ‘philosopher emperor’, had to spend most of his time in the field at the head of his armies, one of which brought back from an eastern campaign the most virulent plague of the Roman era, which spread throughout the empire. At his death in AD 180 the empire was once again undergoing a period of general unease.

Gradual disintegration (AD 180–284)

The previous eighty-four years had seen just five emperors. During the next 104, there were twenty-nine. Alone of the ‘five good emperors’, Marcus Aurelius was survived by a son, Lucius Aurelius Commodus, whom he nominated as his successor.

Commodus had had older brothers, all of whom had died young. He was only nineteen when he became emperor, and he proved a latter-day Nero. Like his predecessor, he initially showed some grasp of political affairs before falling into the hands of favourites and corruptible freedmen. His private life was a disgrace; his public extravagance was prodigious; he fancied himself in the circus; and he died ignominiously – an athlete was suborned to strangle him in his bath in AD 192.

The aftermath of Commodus’ death had echoes of the chaos that followed Nero’s demise, too. He was succeeded by Publius Helvius Pertinax, prefect of Rome and a former governor of Britain. He was murdered just three months later by the imperial guard, who offered the empire for sale to the highest bidder in terms of imperial handouts. The winner was Didius Salvius Julianus, an elderly senator, but there were three other serious contenders out in the field, each with several legions behind him.

Lucius Septimius Severus (AD 146–211), in Pannonia, was the nearest to Rome, which he entered and captured on 2 June AD 193. Didius was soon put to death on the orders of the Senate. Having disbanded the imperial guard and replaced it with his own men, Severus set about coming to terms with his two rivals, Pescennius Niger in Syria, and Clodius Albinus in Britain. He defeated them in turn, Niger at Issus in AD 194, and Albinus in Gaul in AD 197.

Severus was born in Leptis Magna, Africa. A professional soldier, he campaigned energetically to maintain the empire’s frontiers in the East, and spent the last two and a half years of his life in Britain, fending off the northern tribes. He made a number of changes to the administration of justice both in Rome and Italy and in the provinces of the empire. Within the army, the top jobs went to those with the best qualifications, not necessarily those of the highest social rank. He improved the lot of legionaries by increasing the basic rate of pay to match inflation (it had been static for a hundred years), and by recognizing permanent liaisons as legal marriages (previously legionaries had not been permitted to marry). His philosophy of rule – which he impressed upon his two unruly sons, Caracalla and Geta, shortly before his death – was to pay the army well and to take no notice of the Senate.

Severus had nominated his sons to rule jointly after him, and counselled them to get on with each other. Caracalla resolved this arrangement by murdering his brother, but observed his father’s professional advice by increasing the pay of the army by 50 per cent, thus initiating a financial crisis. Some sources suggest that it was to repair this situation that he granted full citizenship to all free men in the Roman empire. Whether or not that was so, he is credited with taking the final step in the process of universal enfranchisement (which had begun in the third century BC) in AD 212. He was assassinated in Mesopotamia while attempting to extend the eastern front.

Caracalla was succeeded by Macrinus, commander of the imperial guard, who never got to Rome, as he was defeated and killed in AD 218 by detachments of his own troops, who supported the depraved and arrogant Elagabalus (AD 204–22), a cousin of Caracalla. In turn, Elagabalus was lynched by his own guards, having nominated as his successor his young first cousin, Alexander Severus.

Alexander Severus was only sixteen when he took office. That he ruled moderately successfully for thirteen years was due partly to his sensible nature and willingness to take advice, and partly to his mother, Julia Mammaea, niece of Julia Domna, who recognized who would give him the soundest advice. In AD 234 Alexander took his mother on campaign with him to Germany, where they were both murdered by mutinous soldiers the following year.

The new emperor was Maximinus, a giant of a Thracian peasant who had risen through the ranks to be commander of the imperial guard. In AD 238 the Senate tired of him and put up their own candidate. In the ensuing confusion, five emperors died, including Maximinus, who had invaded Italy and was murdered by his own troops.

The survivor was Gordian III, aged only thirteen. With the help of a regent he enjoyed civil and military success until he too was murdered, in AD 244, while in Mesopotamia collecting animals to take part in the triumphal procession in Rome he had been awarded for his victories in Persia.

While the next fourteen emperors came and went (usually violently), the hostile peoples outside the frontiers gathered themselves for the kill. In Germany, the Goths, Franks and Alamanni established the permanent threat to the Roman empire which contributed to its ultimate annihilation.

Gallienus (c. AD 218–268), joint emperor with his father Valerian from AD 253, carried on alone after Valerian was captured by the Persians in AD 259. Gallienus himself was murdered nine years later. Aurelian (AD 214–275), who became emperor in AD 270, temporarily averted the threats from outside the empire and dealt with two dangerous outbreaks of separatism. The breakaway dominion of Gaul, with its own senate, had survived for several years before its fifth ruler surrendered to Aurelian’s army in AD 271. The influential city of Palmyra, under its formidable regent Zenobia, threatened Roman rule throughout the East. The city was finally destroyed after Aurelian had negotiated 200 kilometres of desert at the head of his troops. Zenobia was brought back to Rome to walk in Aurelian’s triumph, after which she was granted a generous pension.

Aurelian was murdered by his own staff, after which the dreadful game of musical thrones continued until AD 284, when yet another commander of the imperial guard, Diocletian (AD 245–313), a Dalmatian of obscure but certainly humble origin, emerged to be proclaimed by his troops.

Partial recovery: Diocletian and Constantine (AD 284–337)

One aspect of the problem was that the empire had always consisted of two parts. Much of the region comprising Macedonia and Cyrenaica and the lands to the east was Greek, or had been Hellenized before being occupied by Rome. The western part of the empire had received from Rome its first taste of a common culture and language, overlaid on a society which was largely Celtic in origin.

In AD 286 Diocletian split the empire into East and West, and appointed a Dalmatian colleague, Maximian (d. AD 310), to rule the West and Africa. A further division of responsibilities followed in AD 292. Diocletian and Maximian remained senior emperors, with the title of Augustus, while Galerius, Diocletian’s son-in-law, and Constantius (surnamed Chlorus, ‘the Pale’) were made deputy emperors with the title of Caesar. Galerius was given authority over the Danube provinces and Dalmatia, while Constantius took Britain, Gaul and Spain. Diocletian retained all of his eastern provinces and set up his regional headquarters at Nicomedia in Bithynia, where he held court like an eastern potentate.

The establishment of an imperial executive team had less to do with delegation than with the need to exercise closer supervision over all parts of the empire, and thus to lessen the chances of rebellion. There had already been trouble in the north-west, where in AD 286 the commander of the naval forces at Boulogne, Aurelius Carausius, to avoid execution for embezzling stolen property, had proclaimed himself an emperor, set himself up as ruler of Britain, and even issued his own coins. This outbreak of lèse-majesté was not finally obliterated until AD 296.

On 1 May AD 305 Diocletian took the unprecedented step of announcing from Nicomedia that he had abdicated; Maximian had no choice but to do the same. While Diocletian’s reign had been outwardly peaceful, the years of turmoil had left their mark on the administration of the empire and on its financial situation. He reorganized the provinces and Italy into 116 divisions, each governed by a rector or praeses, which were then grouped into twelve dioceses under a vicarius responsible to the appropriate emperor. He strengthened the army (at the same time purging it of Christians), and introduced new policies for the supply of arms and provisions. Diocletian’s monetary reforms were equally wide-ranging, but though the new tax system he introduced was workable, if not always equitable, his bill in AD 301 to curb inflation by establishing maximum prices, wages and freight charges fell into disuse, its effect having been that goods simply disappeared from the market.

Confident of his own safety, Diocletian had built for his retirement a palace near Salona in his native Dalmatia. He lived there until his death in AD 313, passing the time gardening and studying philosophy, while refusing to take sides when the system of government he had devised almost immediately foundered.

On his retirement, Diocletian had promoted Galerius and Constantius to the two posts of Augustus, and appointed two new Caesars. Trouble broke out when Constantius died at York in AD 306, and his troops proclaimed his son Constantine as their leader. Encouraged by this development, Maxentius, son of Maximian, had himself set up as emperor and took control of Italy and Africa, whereupon his father came out of his involuntary retirement and insisted on resuming his imperial command. At one point in AD 308 there seem to have been six men styling themselves Augustus, whereas Diocletian’s system allowed for only two. Galerius died in AD 311, having on his deathbed revoked Diocletian’s anti-Christian edicts. Matters were not fully resolved until AD 324, when Constantine defeated and executed his last surviving rival. The empire once again had a single ruler.

Constantine’s appellation ‘the Great’ is justified on two counts. In AD 313, he initiated the Edict of Milan (that city was now the administrative centre of Italy), giving Christians (and others) freedom of worship and exemption from any religious ceremonial. In AD 325 he assembled at Nicaea in Bithynia 318 bishops, each elected by his community, to debate and affirm some principles of their faith, resulting in the Nicene Creed. Though he was not baptized until just before his death in AD 337, he regarded himself as a man of the god of the Christians, and was thus the first Christian ruler. He also, in AD 330, established the seat of government of the Roman empire at Byzantium (which he renamed Constantinople, ‘City of Constantine’), thus ensuring that a Roman (but Hellenized and predominantly Christian) empire would survive the inevitable loss of its western part.

To the Jews, Constantine was ambivalent: while the Edict of Milan is also known as the Edict of Toleration, Judaism was seen as a rival to Christianity, and among other measures he forbade the conversion of pagans to its practices. In time he became even more uncompromising towards the pagans themselves, enacting a law against divination and finally banning sacrifices. He also destroyed temples and confiscated temple lands and treasures, which gave him much-needed funds to fuel his personal extravagances.

A military commander of considerable dynamism, Constantine developed Diocletian’s reforms, and completed the division of the military into two arms: frontier forces; and permanent reserves, who could be sent anywhere at short notice. He disbanded the imperial guard, and established a chief-of-staff to assume control of all military operations and army discipline. Under him, the praetorian prefects, who had held military ranks while also being involved in civil affairs, became supreme appeal judges and chief ministers of finance.

The fall of Rome

Constantine had intended that on his death the rule of the empire should devolve to a team of four: his three sons – Constantius, onstans and Constantine II – and his nephew Dalmatius. To form a tetrarchy on a dynastic principle was, however, more than the system could stand. Dalmatius was murdered, the brothers bickered, and the empire splintered again.

The pieces were retrieved after Valentinian was nominated as emperor by the troops at Nicaea, on condition he appoint a joint ruler. He chose his brother Valens (c. AD 328–378); no one dared oppose the appointment. The brothers made an amicable East–West division between themselves. The empire was briefly united again in AD 394 under Theodosius (c. AD 346–395), who established Christianity as the official religion of the empire. It was also he who revenged the lynching of one of his army commanders by inviting the citizens of Thessalonica to a circus show and then massacring them in their seats, for which the Archbishop of Milan persuaded him to do public penance. Under his sons Arcadius (c. AD 378–408) and Honorius (AD 384–423), the eastern and western parts of the Roman empire finally went their separate ways.

At some point in the fourth century AD the Huns had set out inexorably westwards from their homelands on the plains of central Asia. They displaced the Alani, who lived mainly between the rivers Dnieper and Dniester, who displaced the Vandals, who in turn swept right through Gaul and Spain, and even into North Africa. Also displaced were the Goths, who bordered the Roman empire on the far side of the Danube. Britain was now abandoned to determined waves of Picts, Scots and Saxons, and the legions were rushed to the final defence, no longer of the empire, but of Rome itself.

In AD 410 Rome was captured and sacked by Alaric the Goth (d. AD 411), after he had only the previous year accepted a bribe to leave it in peace. Though Pope Leo (d. AD 461) managed in AD 452 to negotiate terms with Attila the Hun (c. AD 406–453) to leave Italy after he had ravaged much of it, three years later it was the turn of the Vandals: Rome was sacked again, this time from the sea. Finally, in AD 476, Odoacer (d. AD 493), a German mercenary commander, deposed the fourteen-year-old emperor Romulus Augustulus and informed Zeno (d. AD 491), emperor of the East, that he would be happy to rule as king of Italy under Zeno’s jurisdiction. Effectively, the Roman empire in the West was at an end. The Roman Catholic Church now assumed the role of unifying the lands and peoples which had formerly been Roman, organizing its sphere of influence along Roman lines.

There is rarely a single cause of catastrophic disasters. Civilizations less stable and less well organized than Rome have survived economic failure, political and administrative incompetence, plague, class divisions, corruption in high places, decline of moral standards, and the necessity of changing the structure and status of the workforce. Ultimately, what hastened the end was the failure of the very instrument by which the empire had been founded, the Roman army. The policy of dividing it into frontier forces and mobile field forces which could be dispatched to trouble spots had a serious disadvantage: however effective communications might be, the infantry had to march to its destination.

The eastern Roman empire, largely by reason of its geographical situation, was bypassed by the hordes of invaders. Its capital, Byzantium, had first been reconstructed in the time of Septimius Severus not just as a Roman city, but modelled on Rome itself, on and around seven hills.

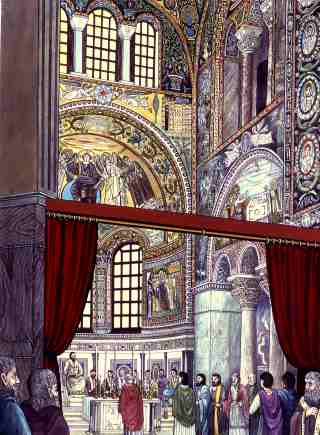

The building of a racecourse on the lines of the Circus Maximus where there was insufficient space for it was not beyond the skill and ingenuity of the architects. It was constructed on the flattened summit of a hill, with one end of the stadium suspended over the edge on massive vaulted supports. Eastern influence led to the development of a distinctive style of Byzantine architecture, with the dome a predominant feature, and interiors richly decorated.

Justinian ruled from AD 527 to 565 and is said to have been eighty-three years old when he died. His aims included stamping out corruption in government, refining and upholding the law, uniting the churches in the East, and taking Christianity forcibly to the barbarians in the West. In pursuit of this last aim his generals tore into the barbarian kingdoms and temporarily restored to the empire its former African provinces and northern Italy, as well as the city of Rome itself.

In AD 532, during the reign of Justinian, much of Byzantium was destroyed during a rebellion that began as a riot between two sets of fans in the stadium. The damage enabled Justinian to exploit the situation at a time when the golden age of Byzantine architecture had just been reached. The sensational church of St Sophia still survives (albeit as a mosque since 1453).

Justinian’s wife Theodora, an actress, proved until her death in AD 548 an admirable foil and support for her husband. She stood up for persecuted members of the heretical Monophysite sect, with whose views she sympathized, and comforted Justinian in times of stress.

While the eastern empire was largely Greek in its mores, it still upheld Roman law. The Justinian Code (AD 529) brought together every valid imperial law. In addition, Justinian issued a revised and updated edition (AD 534) of the works of the classical jurists, and a textbook on Roman law (AD 533). After him, the eastern empire was Roman only in name. In AD 1053 the Church of the East split with the Church of Rome and in due course begat the Church of Russia. On 29 May AD 1453, Constantinople and its emperor Constantine XI fell to the Turks and the forces of Islam, who had already overrun what remained of the empire’s narrow footholds along the coast of the Sea of Marmara.